Scientist vs Stephen Cooper: The interview

Discussing his partnership with producer Phillip “Winta” James, reggae star Protoje said – in an interview with WaxPoetics, two years before the duo released “A Matter of Time,” one of the most heavily played reggae albums of 2018 – that when they first met, they “bonded on” the period in Jamaican music in the early 1980s, “when producers Junjo Lawes and Linval Thompson had an enduring run of work with the Roots Radics band and the engineer Scientist.”

Describing this same period of time in “Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae,” a seminal book about dub music pioneers such as Osbourne “King Tubby” Ruddock (1941-1989), Michael E. Veal, an associate professor of ethnomusicology at Yale University writes: “Scientist’s work reflected the harder mood in Kingston during the early 1980s”; Scientist’s unique mixing style “grew to sound harder, more urban, and more electronic than those of the earlier engineers at Tubby’s.”

Protoje said he even told Winta James before they teamed up on Protoje’s 2015 album “Ancient Future”: “That’s where I’m trying to go with the music. [Because] Scientist is who I really got in touch with[.] My favorite dub album ever is ‘Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires.’ That changed my life. I heard that in [the video game] Grand Theft Auto. That’s what opened me to dub music.”

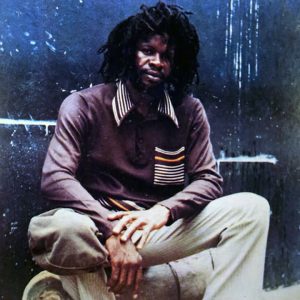

Being a huge fan of the direction Protoje and Winta James have steered reggae music, and, because I too fell in love with dub through music engineered by Scientist, née Hopeton Brown, it was a great honor for me, at the tail end of last year, to not only meet Scientist, but to befriend him, too; we got to know each other and developed a mutual respect over the course of several very interesting and enjoyable phone conversations, and also, a lengthy in-person interview, on December 30, at a Thai restaurant across the street from Los Angeles’s historic Dub Club – a trendy spot for reggae in Los Angeles – a place that wouldn’t even exist without the innovations of Jamaican sound engineers like Scientist.

What follows is a transcription of “Round 1” of what will be a multi-part series encapsulating my extensive conversation with Scientist (“Round 2” will be released several weeks from now); it has been modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Mr. Brown, thanks again for taking the time to do this interview. I understand you just came back from doing a few shows in the U.K. with Winston Williams, also known as “Horseman.” How did that go?

Scientist: It went very well.

Q: Seeing as you were present in mostly all of the top recording studios in Jamaica when roots reggae and dub were born, and when many believe they peaked, in the 1970s into the early 1980s, and, that there’s no question [that] history will record you as [being] one of the greatest innovators and pioneers of the music, I have a lot to ask you today!

Scientist: Okay.

Q: As you said when we scheduled this interview, there exist many falsehoods and misconceptions about yourself and your highly distinguished career, many of which I hope we can address.

Scientist: Yes.

Q: Just to clear up some basic biographical information, I want to start with your name. Not the title of respect “Scientist,” by which everyone knowledgeable about reggae and dub [music] knows you. The story of how [famous Jamaican music producer] Bunny [“Striker”] Lee, together with King Tubby, christened you “Scientist” because your ideas about mixing and recording music, as well as the technological possibilities of the mixing console (including things like “moving faders”), were more advanced, and more predictive of the future of Jamaican music, and one could argue [by extension], all music, [than anyone else, even though you were but a teenager] – that story has been well told! But, in reading about you, I noticed that journalists and writers alternatively refer to you as “Hopeton Overton Brown,” “Overton Brown,” “Overton H. Brown,” and other similar permutations. What is your full birth name?

Scientist: My full birth name is “Hopeton Brown.” Those who know me from kindergarten know me as “Overton.” My Jamaican side of the family all call me “Overton.”

Q: How come?

Scientist: My grandfather mostly used to call me “Overton.” So anybody who knows me well from short pants-days, they know me as “Overton.”

Q: Now I read that you were raised in a fishing village called Harbour View, near the Norman Manley International Airport in Kingston[,] [Jamaica]. Is that accurate?

Scientist: Yes, that’s very accurate.

Q: And is Harbour View also where you were born in 1960?

Scientist: No, I was born in a more western part of Kingston. My first remembered residence was [on] Waterloo Road.

Q: What was Harbour View like growing up? What are some of your fondest memories of it?

Scientist: Learning how to smoke weed. (Laughing.) [And] I learned about His Majesty, Haile Selassie [I]. [Which] helped me to change some of my ways. Because I was getting ready to be on the wrong side of life. I met a couple of Rasta people out there. And they taught me about colonialism. [About] [h]ow the world is run by certain individuals, and what real Babylon was. So after that, I started to go on the right side of life.

Q: Now in an interview with DJ 745 last month in the U.K., you said you grew up with your grandparents.

Scientist: Yes.

Q: Specifically, you said they wanted you to grow up to be one of “those people [wearing] a suit and tie.”

Scientist: Yes. A lot of people grow up with a misconception that everybody in Jamaica smoke[s] weed. My grandfather was a police inspector. I was the embarrassment to the family.

Q: Wow. [You were the] [b]lacksheep?

Scientist: Yeah. They wanted me to take the bar [exam] like you, [become] a lawyer like you. [But] I hate suits. I hate dressing up. I couldn’t wear the uniform every day. I didn’t like going to church [and] dressing up every Sunday, choking [in] a tie. And then I would notice the same pastor pass all of us at the bus stop baking in the sun. Or getting wet in the rain. And he alone [was] driving an expensive car going to church.

Q: Hypocrisy?

Scientist: Hypocrisy! And then he talking about “oneness” and love.

Q: I was curious whether you lived under the same roof with your grandparents –

Scientist: Yes.

Q: – and also your father and mother?

Scientist: [Just] [m]y grandparents.

Q: Did there come a [time] where your family saw [that] you were successful in music and accepted what you were doing?

Scientist: Later on in life they started to accept it. Because one of the misconceptions was, whenever you see King Tubby in the newspaper, that he was part of a gang. Because every weekend you’d read in the newspaper [that] King Tubby’s sound [system, Tubby’s “Hometown Hi-Fi”] got shot up; police caught all these people with all kind of weapons. So my grandparents thought that [King Tubby] was influencing me the wrong way. I remember one day my grandmother run up to him and say, “You, you! Stop! Stop giving my grandson that thing to smoke!” Poor Tubby. He [didn’t] even smoke cigarettes.

Q: Now I thought that Tubby’s sound system, [his] Hometown Hi-Fi, was one of the [sound] systems that, despite all the politics and the gangs that were clashing, that [Tubby’s] was one of the [sound] systems that everyone respected. That it was apolitical. That either side, PNP or JLP[, the two main political parties in Jamaica], would respect Tubby’s system, because the sound was so good?

Scientist: Yeah, but not the police. Not the police. The police would actually destroy [Tubby’s] [sound] system.

Q: Now I understand that your father worked full-time in electronics, and that at around age 14 you also developed your own interest for electronics by experimenting with old electronic parts you got from your dad. True?

Scientist: Yes, that’s true.

Q: And did your father work at the same electronics store where you got a job yourself as a teenager, on Orange Street, a few doors down from where Bunny Lee had his record shop?

Scientist: No.

Q: He worked at a different shop?

Scientist: He was freelance. A television technician [in the neighborhood].

Q: The [electronics] shop where you ended up working, just to confirm, was called “Lens Radio Electronics,” true?

Scientist: Yes. Seems like you did a lot of homework. (Laughing)

Q: (Laughing) I tried to. When you dropped out of school as a teenager to work at the electronics store, and also, to build and test amplifiers for local sound systems, did your mother and father support this decision? You talked about your grandparents, but I’m curious [also] about your mother and father, especially your dad. Because he was involved in electronics.

Scientist: Yeah, they were more impressed. But my grandfather, being that he was a police[man], he remembered back in the day when [you] used to go to Waterhouse, it was like a “no man’s land.” And then when they discovered that I’m not going to school – I used to pretend like I was going to school. And then, one day my cousin didn’t catch the mail for me. And the mail went straight to my grandmother. “Hopeton Brown has not come to school in six months.”

Q: Wow.

Scientist: When I went home, my grandmother said, “how was school today”? [And I said,] “Good, Grandma.”

Q: Oh man!

Scientist: And, [she said,] “How’s everything?” [I said,] “Good, Grandma.” And she said, “Go get ‘Willy.’” She called the belt “Willy.” I got a whipping from everyone in my family that day.

Q: Wow, Scientist, wow. Well, at least you survived. And you’re still here to talk about it (Laughing).

Scientist: (Laughing) It didn’t stop me. I got so much punishment. But after a while [they] got fed up of beating me. Because it didn’t make any sense. Because I’m going to go to the [music] studio. I’m not gonna go to school. I don’t want to learn about Christopher Columbus.

Q: You followed your passion, music?

Scientist: Yeah. Yeah. And after [a while] they leave me [alone]. But I was the embarrassment to the family. I was the person in the neighborhood – “don’t mix with that kid, he’s mixed up in gangs, he’s going to Waterhouse – ”

Q: [He’s a] [b]ad man?

Scientist: Bad man-business. Poor me. I was never in any gang.

Q: Many past interviews you’ve given have addressed the specifics of how several things King Tubby was doing [sonically] with his “Hometown Hi-Fi” sound system, and in his home studio (at 18 Dromilly Avenue) that really appealed and spoke to your technological curiosity, and further, that it was this interest you had in [the] albums Tubby was making, like “Roots of Dub,” together with introductions and recommendations from Bunny Lee and another friend of yours that led you to working with Tubby. Now, I do want to clarify a few things here. Is it accurate that you were only 16 when you first started working for Tubby, testing and repairing amplifiers, speakers, and other electronics?

Scientist: Yes.

Q: And before you began working with King Tubby, you already had experience working at Studio One for the legendary [Clement] Coxsone Dodd, true?

Scientist: Yes.

Q: When did you start working with Coxsone – even before [you started working] with [King] Tubby?

Scientist: It was on and off. Before and after. Because I was neither full-time at both places.

Q: I’m asking these questions because it seems, truly, you were a child prodigy as a sound engineer to be doing that at such a young age. And I want to explore a bit with you, Mr. Brown, the complex relationships that existed between King Tubby, yourself, King (then “Prince”) Jammy [also known as Lloyd James], and even some of the other famous sound engineers associated with King Tubby’s Studio, like Philip Smart, and [singer] Pat Kelly. Because other than Lee “Scratch” Perry, Errol [“T.”] Thompson, and perhaps also Prince Buster [Cecil Bustamante Campbell] too, [it was] Tubby’s studio [that] was really the birthplace of dub music in the world. And yet, still, there seems to be a lot of inaccurate thinking and reporting as it concerns the dub tracks that were cut at Tubby’s; who was doing the bulk of the mixing; and, the relationships that existed at the time between Tubby and his principal engineers (I mentioned), including yourself. In just about every book, documentary, [and] article about dub music, even panels and conferences you’ve been invited to participate in, you are often introduced or described as having been King Tubby’s protégé, or his apprentice. And Jammy is often described as having been Tubby’s “right-hand man,” the heir apparent, and Tubby’s most accomplished engineer. But you have been pushing back in recent years, and in stronger and stronger terms, against this commonly recited version of events. True?

Scientist: Well, first of all, Jammy was very unreliable. That’s how I got my first break. Because he was supposed to come to the studio to do a session with Henry Lawes, and because I was a kid, Henry Lawes did not want me to work on it. And Tubby said: “The only way you gonna get this record mixed or cut is if you make ‘him’ [myself, Scientist] do it, because I am not doing it.”

Q: And Jammy can’t be found?

Scientist: He can’t be found. He was very unreliable. Jammy was never ever Tubby’s “right-hand” man. The only person that touched the money at 18 Dromilly Avenue was I [and] King Tubby. The only person that had a key to 18 Dromilly Avenue was I and King Tubby. The “Princess” (referring to Jammy) perjured herself in the United States second district court. When the Princess came to court perjuring herself saying he was my boss, he was one of the three directors [at Tubby’s studio] – those are lies!

Q: And I’m definitely going to ask you a number of questions about your litigation with [the] Greensleeves [record label]. And feel free to say whatever it is you want to say about it, but I wanted to point out that on the issue of the misconceptions about the relationships at [Tubby’s] studio, you were interviewed [in the U.K.] by Lioness Izasha, and, when she said, “you’re known as King Tubby’s apprentice,” you pointed out, “King Tubby wouldn’t allow someone without full knowledge and experience to use his mixing equipment and to operate the studio.” Sarcastically and rhetorically, you questioned: “[A]nd they want to call me an apprentice? And I was doing all these things? Wow.” And 10 years ago, in an interview with Angus Taylor for United Reggae, you were even more direct on this point. You said: “Jammys do not have my experience. What live concert Jammys ever mixed with twenty-thirty thousand people? The only place Jammys ever worked was around King Tubby’s at that little piece of hell hole, he set up around there. He doesn’t have my experience. Not even Osbourne Ruddock [(King Tubby)] has my experience . . . working on different types of consoles.” And you’ve pointed out over the years, in a number of different settings, as you [also] just did, when you worked with Tubby, Tubby gave you the key to the studio. And [he] trusted you with collecting and holding the money, not Jammy. And you’ve said before that Tubby’s told you in front of Jammy, don’t allow –

Scientist: “Don’t allow him to touch the money.” And, “Don’t allow him in the studio by himself.” Yes.

Q: And you’ve said quite clearly that you were the one running that place [(Tubby’s studio)], but it’s just, because you were so young [at the time], and because you weren’t in any way protected legally, folks have taken advantage of you in terms of reciting th[e] history [of dub music’s roots]? Am I accurate about this?

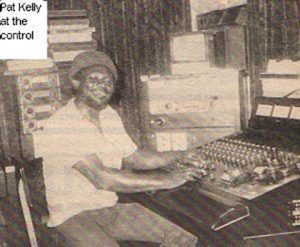

Scientist: Yes. Very accurate. Let me make it clear: there were other people there; thank God to somebody like Pat Kelly, who I can salute, one of the guys in reggae that’s very decent. [He’ll tell you,] Jammy was never my boss. And what used to happen [is] at nighttime, Tubby used to leave the studio from about three or four o’clock in the afternoon. He would only come for about an hour. And then, at nighttime, Bunny Lee would work, and Pat Kelly would be working for Bunny Lee. And Pat Kelly would be mixing the “A” side [of a .45]. (Calling Pat Kelly on cell phone) I’m trying to see if he’ll pick up a call right now. Hello Pat Kelly?

Pat Kelly (by phone): Uh-huh?

Scientist: Hey, we’re doing an interview here and I was just mentioning what went down with me and you [and how] at nighttime you’d be mixing for Bunny Lee, and you’d mix the “A” side, and then you’d allow me to mix the “B” side of the tracks.

Pat Kelly (by phone): Uh-huh.

Scientist: Yeah, because people have a lot of things twisted. A lot of people don’t know that you mix, and that you’re also an engineer.

Pat Kelly: (Laughing) Yeah.

Scientist: Yeah. So I was just trying to mention you in the interview –

Q: Greetings Mr. Kelly! My name is Steve Cooper. I’m hoping someday I can meet and interview you, too. I’m writing a book about reggae music.

Pat Kelly: Yeah?

Q: Yeah. And so I’ve been meeting with all the most famous [and emerging reggae artists] including Scientist, Lee Scratch Perry, King Yellowman, and, and everybody. So I’ll get your contact info from [Scientist] if it’s okay, then maybe I can catch up with you at some point?

Pat Kelly: Okay.

Q: Give thanks, Mr. Kelly!

Scientist: Pat Kelly is one of the people you should interview. Give thanks, Pat. (Hanging up phone.)

Pat Kelly: Okay. Alright. (Hanging up phone.)

Scientist: So Pat Kelly was the one mixing a bunch of tracks at nighttime. And because I was the person to lock up the studio and make sure everything [went] well after Pat worked, Pat would say: “Hey, hey, come on man, you mix the dubs.” And I would mix the dubs. So Bunny Lee and [Pat] would mix the “A” sides. But, during that time, Jammy was never ever allowed in the studio by himself. Why? Because we used to have a guy there, we call[ed] him “CIA.” (Laughing) [And] Tubby would say: “So CIA, what time you leave the studio last night?” [And CIA would say,] “like 4 in the morning.” And Jammy would tell Tubby he left at twelve. (Laughing) So, Tubby was a very smart guy.

Q: Was there ever a point early on when you and Jammy were friends and had a mutual respect?

Scientist: Not really. Not really. His brother –

Q: Jammy’s brother?

Scientist: Yes. Trevor. Looked just like [Jammy]. If you don’t know them –

Q: Does he do music, too?

Scientist: Yeah, he produced a song that ended up in some kind of family feud – Jammy tried to take credit for it.

Q: [What] was the title of the song?

Scientist: “I Know The Score.” By Frankie Paul or one of them that he did. That he produced. And [it was Jammy’s] brother [Trevor that] I had a better relationship with. Because Jammy has been always jealous. And he couldn’t understand why I had such control over the studio when he grew up at Tubby’s. But Tubby’s mother, “Ms. Sissy,” is what people don’t talk about. She would come in front of Tubby and say, “I don’t like Jammy.” And Tubby listened to his mother, like most sons listen to their parents. And she would confront him. All the bad guys in the neighborhood, the gangbangers, it’s like when she come around, it’s like the queen come around. They’re all helping her get off of the bus. Carrying her groceries. [And] [s]he – she would cook for me in the evening and invite me over for dinner.

Q: So you had a strong relationship with [Tubby’s] mom?

Scientist: Yeah, with [Tubby’s entire] family. Tubby’s wife, his daughter . . . . (laughing). Only one thing Tubby say, “You! You’re not getting into my family. Leave my daughter alone! (Laughing)

Q: Now on Valentine’s Day in 2015 you published a very detailed post on Facebook in which you very clearly outline your position concerning your dispute about the 6 dub albums [“Scientist vs. Prince Jammy,” “Scientist – Heavyweight Dub Champion,” “Scientist Meets the Space Invaders,” “Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires,” “Scientist Wins the World Cup,” and “Scientist Encounters Pac-man”] that [the record company] Greensleeves released in the early 80s, without paying you a dime. And again, you also [stated] your position on this in a 2008 interview with Angus Taylor for [the online magazine] United Reggae, but, [have] there been any additional updates or legal developments in [your] [long running legal] dispute with Jammy, Greensleeves, Blood & Fire, VP [Records], etcetera, [concerning your allegations about the theft of your intellectual property and royalties from those 6 dub albums]?

Scientist: Let’s look at what makes sense, alright? You’re an attorney, right? And for thirty years these albums [have] been out. They try to rename the title[s]. And when you look at it, the person who came to court to lie for them, who perjured themselves for [these record labels], is the one [given] credit [for] the album [and on the album cover] when he didn’t have anything to do with the album. So there is a conflict right there in court, right? Where the worker is now testifying for his boss. And then the worker there didn’t have anything to do with the[se] album[s], but yet still they think that they owe him some kind of loyalty.

Q: Are your lawyers still pursuing this? Because people haven’t heard mention of this [in the news] recently, and I wondered if you’re still pursuing [the vindication of] your rights on this?

Scientist: Well, yes. Because, you’re a lawyer as I say, you know what it is to be systematic. When the courts see you as systematic. This is something you are continuously doing.

Q: Litigation, especially civil litigation, takes forever. And I think you’ve said before, and I completely understand, some of these companies, what they do [is try to drag things out], because the litigation costs so much to keep pursuing it – just the cost alone to keep pursuing it – [that] it can be prohibitive. Especially so for artists, I would think.

Scientist: Yes. And then what you have, you have lawyers that are involved in what’s called “willful blindness.” As an attorney, you know exactly what that means. But for people who don’t understand: if you’re working at a mechanic shop and ten years go by and you’re just answering the phone. You know what these guys are doing in the mechanic shop, but you still choose to work there. So it becomes “willful blindness.”

Q: Even though the drugs may be moving in and out of the backdoor –

Scientist: In and out of the backdoor, but you just answering the phone? After a while it becomes willful blindness. And what I find is a lot of attorneys, or some attorneys, they don’t apply what you call “candor.”

Q: That’s for sure. I’ve noticed that in the legal profession. I agree with you 100%, Mr. Brown.

Scientist: Rule 3.3 [of] the American Bar Association –

Q: (Laughing) Wow! When are you going to start practicing law? You know the law, Mr. Brown – I can tell. You’ve been involved in this fight for [a long time]?

Scientist: Well, here’s what I know: I’m not a lawyer [just like] I’m not a mechanic, but I know about cars. My specialty is electronics but you find that a lot of these attorneys do not practice candor. Rule 3.3, when your client is about to commit perjury, do something illegal, you have to deter the client. If that doesn’t work, you have to tell the judge. And if the client still wants to go forward, you have to drop the case.

Q: (Laughing) If you ever want to practice law, Mr. Brown –

Scientist: The judge wouldn’t want me because I would be smoking too much weed. (Laughing)

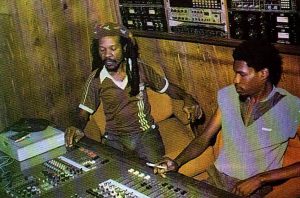

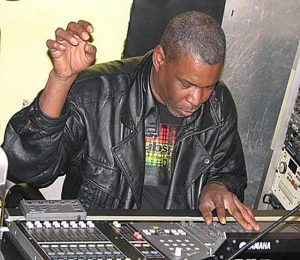

Q: Selecta Jerry, a DJ in New Jersey, sent me a picture of a vinyl pressing [put out] by VP Music in 2016 of [the album] “Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires.” Now as Selecta Jerry observed, it has much of the same artwork that was on your famous album released [in the 80s], except for now, [the album] has been retitled. It doesn’t have your name on it. [Instead,] [i]t’s called: “Junjo Presents the Evil Curse of the Vampires.” And then[, adding insult to injury,] your image? Where you’re at the mixing board? It’s [been] blocked out [entirely] by a big [search]light. You wouldn’t have any idea by looking [at the artwork] that Scientist was involved in [the making of] this [album]. Now, in a 1998 interview you did with Mike Pawka, you said that [this album,] “Scientist Rids the World of the Evil Curse of the Vampires” is one of the best, and [also, your] personal favorite album of all of the [many] albums that you’ve made. Given that, how do you feel about the album cover being manipulated in the way that it has, and also, [the fact] that, if you go on iTunes, a person who is interested in dub music, that is the album that pops up, the “Junjo Presents” [version] without [any attribution or credit to you]? Because [personally], I think this is one of the best [works] of music ever created. And it’s very disturbing to me, and I can’t even imagine as the artist who created it how you must feel about this.

Scientist: Well, here’s what: We had a court ruling that came down against [these infringing record companies] in France. And the illusion that producers own copyrights – do you know about the Berne Convention?

Q: Only because I read about it on your Facebook [page]. (Laughing)

Scientist: Yeah, well in Jamaica and [also] in the United States, [as signatories] to the Berne Convention, anything having to do with drawing, architecture, music, sound recording, anything that you create [there are only a certain number of ways under the law that ownership can pass]. And when we were in court in France, I showed the judge the law. And I asked the judge to rule on the law. The judge ha[d] to [follow] the law. So [these infringing record companies] thought by taking this Lamborghini, [and] painting it black when it was red, and calling it something else – well, when the cop stops it, it has the same VIN number. It has several VIN numbers written all over the car. See the judge has to rule on the law. And when lawyers are involved in willful blindness, and then, when lawyers start to be a part of the crime scene, you know as a lawyer, how the judge feels about that.

Q: Now another related but independent issue concerning the theft of royalties from you, and perhaps the equally or more important theft of recognition and historical musical legacy, concerns many of the same [record] companies we’ve already mentioned, and others too, releasing dub mixes, especially with the famous session band the Roots Radics, but crediting and putting King Tubby’s name on it, not yours. True?

Scientist: True. Listen to what makes sense: Why when Tubby was alive, none of these albums came out? Doesn’t make any sense, right? Why after Tubby died all these albums just suddenly appear? And then here’s what, you remember that stuff that Tubby put out with [Anthony] Red Rose and them? Where all that sound went to? You know what happened? I set the bar so high, that not even Tubby could reach that bar. That’s what makes sense.

Q: [Y]ou’ve said [this] before, and others have [too], [that King Tubby didn’t do as much] mixing as [some] folks [have been] saying [all these years]? [That] [h]e stopped mixing.

Scientist: The last song Tubby mixed for anybody was [Barber Shop Saloon/]“Weather Ballon” with Mikey Dread. And I used to say, Tubby don’t want to mix. Why? Why? Why he doesn’t want to mix. He’s like me now – I don’t really want to mix your song, man. And he would mix none of these songs. But here’s what happened: the bar that was set, and the expectation. Not to be disrespectful, but because the bar was set so high, everybody – and then the misunderstanding about Tubby’s thought. First of all, Tubby [didn’t] deal with apprentices. You either know it or you don’t know it.

Q: That makes sense to me. There’s no time for that in the music business.

Scientist: No time for that in the music business. You either ready or you’re not ready. But the bar was set so high.

Q: In my research on this, I was particularly perplexed by the TV show “David Rodigan Looks at the Life of King Tubby and the Influence of Dub on Today’s Music.” It aired on BBC1’s “Extra Stories” and is easily found on YouTube. Narrating the show, Rodigan asserts, quote, “Hundreds if not thousands of dubs were cut by [King Tubby],” and, that “Tubby mixed thousands of records.” What’s your reaction to these assertions by David Rodigan?

Scientist: Look here. He was not there. He’s going by hearsay. That’s the first thing that makes sense. Why, when King Tubby was alive, none of these albums came out? Why?

Q: I noticed that [in March 2014] you posted to Facebook: “These are the only legit [King Tubby] albums” [on the market]. Then you listed three albums Tubby should be credited with: (1) Dub From the Roots; (2) Roots of Dub; and (3) Tommy McCook’s “Brass Rockers.”

Scientist: That’s the only three albums.

Q: And in June 2013 you posted an old interview [originally posted] by “Silver Kamel” [and available] on YouTube of Bunny Lee. It’s only about twelve minutes in length, but in there is so much critical history of reggae and dub music. It’s a must watch for [anyone] interested in the history of the music. It explains so much. And in this interview, Bunny Lee [says] exactly what you, Scientist, have been saying for many, many years now: [King] Tubby did not mix thousands of dub tunes as David Rodigan and others have asserted – including a number of record companies that have been releasing [all kinds of reissued] albums with Tubby’s name [on them]. The truth of the matter is, many of these dub mixes put out after Tubby’s death, and marketed under Tubby’s name, are actually Scientist mixes. [Work] [f]or which you’ve received no financial compensation. Is that true?

Scientist: Yes. This is what I don’t like with Jamaican producers. Jamaican producers [have] got things twisted. You might own the master tape, but what was the producer doing? Standing up in the studio giving [out] high-fives? And so the Jamaican producers are just looking for new ways to make money. And guess what? When you talk to [legendary bass guitar player] [Errol] Flabba Holt [for example], [ask him] about how the producers register everything 100% to themselves. So Flabba Holt don’t get no money. Pat Kelly [is] going through the same thing. First of all, you can’t have a contract with a dead man. When the artist is dead, you have to settle the estate. And, you see, they don’t like to deal with me. Well you see, I have a contract. The person died. So a dead man can’t enforce his contract. So I say, “what are you talking about?” Well you can’t have a contract with a dead person.

Q: I have trouble imagining the frustration you must feel about these issues. Now nothing I’ve said, or [that] you’ve said, or that Bunny Lee said in that interview [posted by Silver Kamel], is meant to show any disrespect to King Tubby and his legendary and tremendous contributions to Jamaican music. And, as you’ve said before on numerous occasions, you had a tremendous relationship and a mutual respect with Tubby?

Scientist: Yes.

Q: Indeed, in a September 2001 interview you did with Michael Veal, associate professor of ethnomusicology at Yale University, you said: “Tubby’s [sic] is somebody I saw every day of my life for about five, six years. Not a day passed and I didn’t see him. We was very close. A lot of people thought I was his son!” And so despite the fact that you have publicly complained about the release of dub mixes you made, that have [been released with] King Tubby’s name on them, that hasn’t dampened at all the fondness of the memories and the bond you had with King Tubby – true?

Scientist: True. Look here, Tubby gave me a break, one of the biggest breaks in life. Without any doubt. A lot of people couldn’t believe it. Tubby allowed no one to touch his money –

Q: But you. A young kid like you [were, at the time]?

Scientist: And guess what? My two pockets filled with money every day. In the middle of Waterhouse [an economically depressed, but artistically rich area of Kingston]. And not one person ever bothered me. Not one person ever bothered me about money, or tried to rob me. But I was not a part of a gang. I was running the studio. And when you look at what makes sense, where was Jammy’s name during that time on the albums? Where was Tubby’s name during all that Greensleeves time on the albums? Why? Because [I] set the bar so high. Why after I left Jamaica all that stopped?

*Check back in a few weeks for the continuation music fans, “Scientist vs. Cooper (The Interview: Round 2)”!

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq