Sly Dunbar: 10 minutes with the superstar drummer

Sly Dunbar is one of the most innovative and influential drummers of all time. Individually and together with his “riddim twin” bassist Robbie Shakespeare, Dunbar has played with the biggest names in reggae (Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Dennis Brown, Black Uhuru . . . the list is endless), giant stars in other genres (Grace Jones, Bob Dylan, and The Rolling Stones, to name but three), and produced a treasure trove of hit songs, songs everybody knows and loves that will stand the test of time.

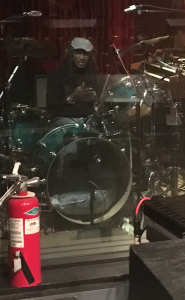

On February 19, thanks to legendary sound engineer Scientist (also known as Hopeton Brown), I was introduced to Mr. Dunbar at Studio City Sound (in Studio City, California). Dunbar and Shakespeare were working on a project with Scientist, Odel Johnson (a versatile Jamaican-born, Canadian-based artist), guitarist Tony Chin, and keyboardists Franklyn “Bubbler” Waul and Michael Hyde.

Although Mr. Dunbar was extremely busy and under considerable time pressure, he graciously agreed to speak with me for a few minutes as the musicians finished their preparations for recording. We spoke about his memories of Bob Marley and Dennis Brown, how Bob Marley would feel about the “state of reggae music,” why Dunbar and Shakespeare left Peter Tosh to play for Black Uhuru, the Grammy Awards, the best recording studios, and finally, the Jamaican government’s failure to properly honor some of the country’s most talented and accomplished reggae musicians. What follows is a transcript of the interview, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Recently we celebrated the 74th earthstrong celebration for Bob Marley. Are there any memories you immediately think of when you think of Bob Marley?

Sly Dunbar: I think of Bob Marley as a great icon who was part of the movement of [making] reggae what it is today. And I remember Robbie and myself used to go and check him when he used to come out to New York. And we’d talk, and sometimes we’d buck up in the music store and he’d always say to me, “Sly, you should open up a music school in Jamaica. A music store.” And I’d laugh. And he’d always say to me he wanted me to come play a whole album for him. And because I used to play with Peter Tosh, he’d always run a joke and say, “you don’t want to come play with us?” And I’d say, “No, man.” And then one night when he come back out of exile – he’d been away from Jamaica for a while, when he got shot – and Lee Perry kept [a] session, [and I] went over to Lee Perry’s studio, and we did like three tracks with him and I did –

Q: Punky Reggae Party [was one]?

Sly Dunbar: Yeah, the recording of Punky Reggae Party. Yeah.

Q: Do you think if Bob were alive today he’d be happy with the “state of reggae music” in the world?

Sly Dunbar: He would change it. He would go and write some wicked songs. Because he was a part of the movement. He never really shun it, you know? And when he hear a movement’s coming, he always join it. Because he’d know it was an evolution, and you can’t hide [from] it. So he would be a part of it, yeah man.

Q: Would [Bob Marley] be happy with the direction the music has moved in?

Sly Dunbar: Yeah he would be happy because he would set the trend, and everyone would follow.

Q: You also worked closely with Dennis Brown. I know you [played] on [his] original “Money in My Pocket.”

Sly Dunbar: Yeah. And the re-cut.

Q: When you think of Dennis Brown, what are one or two of your memories [of him] that come to mind?

Sly Dunbar: He [was] a great performer. Been playing with him [since] we were very young, [back when he was in] a band called the Falcons. And I did a tour with him. And I did a lot of recordings with him. He [was] a true artist. A great person. And a very loving person. A very kind person. A great icon.

Q: So much is written about Bob Marley. Is there anything about Bob Marley that you think is not emphasized as much as it should be?

Sly Dunbar: He was a great person. He was a nice person. I [was] around him quite a bit. The times I [was] around him [he was] a very cool person. He [was] into his music, you know? His music [came] first.

Q: You have said before that when you [played] with Peter Tosh, that [that] was one of the most experimental times in reggae [history], and that you guys were really experimenting with the music –

Sly Dunbar: Yeah, yeah. In that time, in the 70s there was a time when we started to experiment [with] reggae. Reggae started to open up into different areas, you know? And Bob seen it. He wanted to be a part of it, too. Which he did. He was a part of it. He came and he made a song called “Exodus.” In the kind of rhythm we were making at Channel One [recording studio]. So Bob is like a groove master. He would listen to what is happening. And if he was here today, he would make some wicked [music], because he was always [attune to] the next movements for reggae.

Q: Why did you decide to move from playing with Peter Tosh to working with Black Uhuru?

Sly Dunbar: Because we [(Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare)] were producing all these artists while we were playing with Peter. [And] Black Uhuru music is like a different kind of groove from what we played for Peter. It was a hardcore cutting-edge thing [and] we felt we couldn’t play that style for Peter, because he wasn’t singing that kind of music. So we played Peter’s music just the way he sees it. And we play[ed] Black Uhuru music the way we [felt] it, and thought it [should be].

Q: What are your thoughts about Sting and Shaggy winning the Grammy this year for Best Reggae Album?

Sly Dunbar: It’s great. ‘Nuff respect and congratulations to them both, you know?

Q: The Grammys are often criticized for being biased against female reggae artists. Also they’re criticized for being biased in favor of the Marley family –

Sly Dunbar: I don’t know. I don’t know.

Q: Are the Grammy [awards] still meaningful for reggae fans to pay attention to?

Sly Dunbar: Well, it’s meaningful for reggae artists. Because you get that [award] in your hand [and] you always cherish it. Because you look at it and say this is the work I’ve done over the years.

Q: And it opens doors that might not otherwise be open?

Sly Dunbar: Yeah.

Q: Selecta Jerry, a DJ in New Jersey whose show I listen to called “Sounds of the Caribbean,” a show he inherited from [rocksteady icon] Keith Rowe, he played a song last week called “Jah Children Dub.” It’s a wicked song [and] it says on the .45 that you’re featured on it. And Selecta Jerry wanted to know if you were just featured in the dub on that? It’s a tune [produced] by Roberto Sanchez, and it says [on the label] that it features you.

Sly Dunbar: Well there are so many records I play on, sometimes I don’t remember [them]. (Laughing) But if it says that on the record, that’s it.

Q: (Laughing) It’s a great tune. A lot of [really] good [roots reggae, rocksteady, and dub] music is coming out of [producer] Roberto Sanchez’s studio in Spain.

Sly Dunbar: Yeah.

Q: He’s been working with Keith and Tex releasing new music, and he’s been working with you as well. Why is his [studio] able to produce such good, old school-vibes over there?

Sly Dunbar: Well this is what he’s focused on. And he probably [went] and researched the music [because] this is what he wants to do. And [he] realized how to put the music together. So he probably did it in that manner. And you stick with it. And perfect the thing.

Q: You’ve played in so many studios, Mr. Dunbar. What are the best recording studios in the world today?

Sly Dunbar: Today? (Laughing)

Q: Yeah, [or ever]. When you think of [studios] where you would most like to play, [which] are some of the best ones?

Sly Dunbar: Alright. Alright. Let me tell you some of the best recording studios. There are a couple of studios where I think my recordings came out very great: (Nassau) Compass Point [studio] with Grace Jones, Channel One studio, and Dynamic Sounds studio. We did Serge Gainsborough’s album at Dynamic Sound. We did all the Black Uhuru stuff and heavy stuff at Channel One. And some of the Taxi [Cab label] stuff. And the Grace Jones project at Nassau. Those three studios I think the recording was very great for me. They made the drum sound good.

Q: Do you have drum kits on all continents of the world?

Sly Dunbar: (Laughing) No, no, no. I live in Jamaica.

Q: One [last] question that I always ask reggae artists. Why is it that there seems to be such a lack of support even now with the Jamaican government in terms of both honoring the veterans –

Sly Dunbar: I don’t know, you know? ‘Cause I don’t care if they honor me or anything like that. I don’t know. But I think they should. Because there are a couple of people that have done some great work. Even this drummer by the name of Joe Isaacs. He did a lot of stuff. He played on Johnny Nash, not “I Can See Clearly,” [but] the first Johnny Nash song “Hold Me Tight.” And he played on a lot of Studio One [records]. He was the one who started playing rocksteady.

Q: And he hasn’t received any recognition [from the Jamaican government] for that?

Sly Dunbar: No, no. He hasn’t received anything. A lot of people don’t know the history of the work musicians have done in Jamaica. So we’re trying to organize to see if he could get an O.D. [(Order of Distinction)] or something for the work he has done. He put in a lot of work.

Q: It seems there are a lot of [very accomplished Jamaican] artists I’ve come across like Keith and Tex, Scientist, [many] who’ve never been [properly] recognized by the Jamaican government [for their tremendous musical achievements].

Sly Dunbar: Well like for Joe Isaacs, he has [played on] so many songs. The Jamaican government doesn’t keep track of what recording artists do. Somebody has to be assigned in the culture [ministry]. Somebody has to go and tell them because they don’t know. Because there’s no [serious] collection of anything [concerning reggae music history and artifacts] there. Remember [back] in those days, musicians’s names weren’t recorded. Nobody knew who played [on recordings when they were released]. It just kinda changed when [Robbie and I] started doing recording in the 70s. [Musicians’s] names started appearing on record jackets. People would see the musicians who were playing. But Joe Isaacs has played on all these songs, and nobody knows his name because he was never mentioned. Me, as a drummer, I could hear the sound and tell his style of playing.

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq