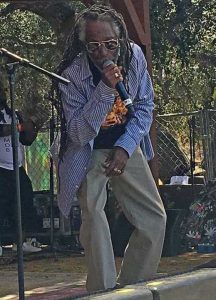

Rootsman Garth Dennis reflects on Reggae’s richness

Rudolph “Garth” Dennis occupies a storied, honorific place in the history of reggae music: In addition to a lengthy stretch as a lead singer for foundational roots reggae band Wailing Souls, without Mr. Dennis, Black Uhuru — the world’s top-selling reggae band after Bob Marley and The Wailers — would never have existed, period/full stop. Since interviewing Duckie Simpson in 2016 and Don Carlos in 2017, the other two original members of Black Uhuru, I’ve been angling to interview Mr. Dennis too; not only to complete the circle, but because Mr. Dennis, through familial relations, friendships, and multi-fold musical connections, is both a witness and an integral participant in the development and expansion of reggae as a genre.

Finally, last month in Los Angeles, after smoking several strong spliffs together, I got the chance I’d been waiting for: I interviewed Mr. Dennis on a hardwood bench in Chinatown for approximately forty-five minutes. We discussed several interesting subjects including: Mr. Dennis’s involvement in his sons’s roots reggae band “Blaze Mob”; the origins of Black Uhuru featuring Mr. Dennis’s insights into the complex relationships that both united and separated its founding members; Mr. Dennis’s 2015 debut solo album “Trenchtown 19 3rd Street”; Rastafari; Mr. Dennis’s special remembrances of Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, and Mr. Dennis’s brother-in-law Joe Higgs (“the godfather of reggae” music). What follows is a transcription of the interview, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Mr. Dennis, thank you for inviting me tonight to the listening party for your sons’s [Shaka “Rock” Dennis, “King” Saeed Dennis, and Gyasi “Gong” Dennis, also known as “Blaze Mob”] new album, “Words Carved in Stone.” You must be very proud of them?

Garth Dennis: Definitely, definitely.

Q: How much are you involved in their music?

Garth Dennis: Not that much anymore now. ‘Cause they’re more mature.

Q: Were you more involved in the making of their first full-length studio album, “More Consciousness”?

Garth Dennis: On and off. Whenever they needed any instruction, I’d chip in. But the majority of that record was done on their own [too]. My son’s grew up around me and my groups you know, like The Wailing Souls and Black Uhuru. The harmonies. And sounds and ‘tings. When I played and they were around, we’d jam together; so a likkle rubbed off on them, you know?

Q: Did you always want your sons to follow your path, and choose careers in music?

Garth Dennis: No. Not definitely. What really happened is a lot of times when I’d come off of the road, I’d usually bring back an instrument. Sometimes a bass, sometimes a keyboard, sometimes a guitar. And they[‘d] just pick it up from there. Plus, their grandma had a piano at the house, so –

Q: So you couldn’t stop them from it –

Garth Dennis: Yeah. Naturally. Yeah.

Q: Were you concerned at all when you saw that music was the path they were heading down? The life of a musician is not always easy, especially [when] you’re starting out; were you worried for them at all?

Garth Dennis: I wasn’t worried at all because [the] material part of it is not why they started [doing music]. That wasn’t a problem, you know what I mean? Yeah. It just happened natural — and they’re very talented.

Q: What are some [of the most important nuggets of advice] you’ve tried to pass on to your sons about music?

Garth Dennis: Make music that uplifts people. Good music. Music that lives on. [Music] [t]hat’s timeless.

Q: Mr. Dennis, at the end of last month, the Jamaica Observerpublished an article called “Battle over Black Uhuru.” It concerned news that Michael Rose is challenging Duckie Simpson in court in the U.K. for the right to use the name “Black Uhuru.” What’s your reaction to this development; what are your feelings about that?

Garth Dennis: My reaction to this is all the guys need to talk the truth. They need to come together and talk the truth. I formed that group. The name [Black Uhuru] was given to I-man, Garth Dennis. And the person who gave I the name, so I could name the group “Black Uhuru,” that person is still alive.

Q: What’s that person’s name?

Garth Dennis: His name is Roy Palmer.

Q: Roy Palmer?

Garth Dennis: Yeah, Roy Palmer. Yeah.

Q: Is he in Jamaica?

Garth Dennis: I think he’s somewhere in the [United] States, here.

Q: Ok.

Garth Dennis: He can be found.

Q: He came over from Jamaica?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. Yeah. He’s the one who present[ed] the name to me. And I tell it to the rest of the brethren. Because I was the first — I put the group together.

Q: Referring to the legal fight over the Black Uhuru name that both you and Don Carlos had with Duckie in the late 1990s, Duckie was quoted in the Observer piece, stating: “This is so weird, I don’t even understand the motive. Is the same thing Don (Carlos) did” — and I think he also meant to include you as well — and quote, “the court award me the name.” What’s your response to these statements?

Garth Dennis: First of all, I must let the world know that [Duckie Simpson] is the one who sued Don [Carlos] and me over the name. And what really happened is: He sued us in the [United] States while we were on tour. We invite[d] him to come along and he refused, right? What really happened is, there’s a show in Jamaica called “Air Jamaica Jazz and Blues Festival” which we were booked on as Black Uhuru. We asked him to come along, and he didn’t come along. What he did was he went ahead and sued us in Jamaica over the name “Black Uhuru.” [And] [i]n Jamaica, myself and Don Carlos won the rights to the Black Uhuru name. In Jamaica! [Laughing.] After we won that name, [Don Carlos and I] went ahead and did that Air Jamaica festival as Black Uhuru. We didn’t [go] to the press, or the TV, or the radio stations to say: “Oh, myself and Don just won the rights to the name of Black Uhuru — in Jamaica where the group was formed!” We didn’t [go] to the press and do that while the [second] court case [Duckie Simpson brought — and eventually won — over the Black Uhuru name] was still going on in America. Or anything like that. Because that’s not what [Don Carlos and I] were involved in.

Q: Do you think that that would have made much of a difference if you had?

Garth Dennis: Much, much of difference! Because that’s in Jamaica where the group is formed — that’s where we [had already] won the rights to the name of the group.

Q: Do you feel like your lawyers in the United States who were representing you [when Duckie brought that second court case over the name] did a disservice to you then?

Garth Dennis: Exactly! They didn’t do a good job. Because they didn’t even mention that.

Q: Because what you’re saying is the fact that you [and Don Carlos] had already won the right to the Black Uhuru name in Jamaica should have meant [more] to a U.S. court if a lawyer had properly [argued] it?

Garth Dennis: Exactly! But that wasn’t presented. In fact, myself and Don [weren’t] even in court when the decision was [rendered]. We were on the road performing as Black Uhuru. And then we were sued twice by Duckie. We [, Don and I,] didn’t do no suing, none at all. So we won the name officially in Jamaica where Black Uhuru [originated]. And as I said before, the person who came up with the name is the right person to interview about where the name came from –

Q: People should be asking Mr. Palmer about that?

Garth Dennis: Exactly! And then they’ll know the truth.

Q: On a different note, isn’t Michael Rose a brethren of yours? Isn’t he one of the Waterhouse singers you mentored and helped to rehearse when he was younger?

Garth Dennis: Yeah, we all grew up together. When you say “mentored,” Michael Rose was always a good singer. But when he joined Black Uhuru, by that time I [wasn’t with Black Uhuru and had joined] Wailing Souls; [but I still] used to rehearse Duckie and Michael Rose, trying to [help them] find a third person for Black Uhuru.

Q: So even when you were no longer with Black Uhuru you were trying to help them?

Garth Dennis: Trying to help them all along. It’s not until the group went through all kinds of different changes with Michael [Rose], Junior Reid, and so on, [that Duckie] came to look for me, to explain to me what was happening. We did a show in the [United] States and Don was on the bill as a solo artist, and I was on the show as a solo artist, and Black Uhuru was on the show [too]. And Junior Reid couldn’t make it. Duckie and the female [backup] singer was there, but they didn’t want to perform. [And] there was an individual who was there that knew all three of us were from Waterhouse — Don, myself, and Duckie — and he said, “all three of you [original Black Uhuru members] are here, go [and perform]!” So we do a couple of songs for the crowd that day. We didn’t regroup right away. Three years after that, [Duckie] came to stay at my house for a while. That’s when he [told] my wife I was the founder of the group. Because when he was about to leave to Jamaica, he said to her for the first time: “Didn’t you know that Garthy formed the group? What’s wrong with you?” And he didn’t tell my wife that all those years [before]. He was the one that said that to her.

Q: Putting aside the courts fights, bad blood, and disagreements that have separated you, Don, and Duckie, the founding members of Black Uhuru [except for when, as you were just discussing, Black Uhuru famously reunited, leading to four critically acclaimed albums in the 1990s including the Grammy-nominated “Now”], the three of you must have been very close friends when you first started out together in the early 1970s, true?

Garth Dennis: Very close. Duckie used to stay with me at my house when the group was formed at 14 Balcombe Drive. That’s where he used to stay when I first put the group together. So it was very close. Don [Carlos] was just down the road, Michael Rose was at the top of the road, [and] Junior Reid [lived] around the corner.

Q: Do you remember how and where you, Don, and Duckie first met each other? Who became friends with who first? [And] [w]as this in Trenchtown, or was it in Waterhouse? How did you get together with them?

Garth Dennis: When I moved from Trenchtown to Waterhouse, I used to still go visit Bob [Marley] and the Wailers and so on in Trenchtown –

Q: On 3rd Street?

Garth Dennis: We were at 1st Street this time. We moved from 3rd Street. We start[ed] at 3rd Street but we moved from place to place –

Q: Sure.

Garth Dennis: — wherever we find [a] vacancy to play.

Q: Different [groups of singers] would be singing [on] different streets?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. Yeah. So I met Duckie [first] in the neighborhood at Waterhouse. I used to see him on the corner when I go to and fro, to and fro. But I [also] remember[ed] him from school in the earlier days. And by the time my parents migrate a-foreign, friends start to come to the house, come to the house. So he was one of those guys who would [always] come to mi yard. And eventually he started to stay there with me. And I start[ed] [to] make Duckie accompany me to some of the rehearsals in Trenchtown. He never used to sing at the time, he just used to be there. When he came back with me to Waterhouse, we start to do our own jamming. And that’s when I put Black Uhuru together.

Q: Nice!

Garth Dennis: And there was a man, an elder called “Jah Vic” or “Jah Victor,” [who had a place] where we used to go and smoke and recreate ourselves. [And] Don used to live in that era in Waterhouse in a place we call “Balmagie.” So when we used to go around there, that’s where I met Don [Carlos] and he started to jam with [Duckie and I].

Q: How old were you guys?

Garth: Maybe early twenties.

Q: Interesting. Because I assumed you just always had a stronger friendship with Don [Carlos than with Duckie], but actually, you were closer with Duckie first. Between the two of them, is there one that you always had a stronger relationship with? Or was it just different with each of them – and you couldn’t choose one over the other in terms of who you were better friends with? Or, could you choose one?

Garth Dennis: Well, it’s not [important] to choose one. But, you know, people carry different vibes. Don carries a whole different vibe from Duckie; Duckie carries a whole different vibe from Don. But it’s one love every time, you know what I mean?

Q: When I interviewed Don Carlos in April 2017 in San Diego, I asked him if there was any chance of the three founding members of Black Uhuru “peacing it out” [and reuniting once again]. And Don said: “I don’t carry any grievance. I want my heart to be light like a feather. I don’t say we can’t get together again, you know. We can. If it’s going to happen it just has to benefit me [too].” Do you feel the same, would you never say never to a second Black Uhuru reunion, as long as it [also] benefitted you too? Is it possible for you guys to reunite [still]?

Garth Dennis: Yeah, it’s possible. But it’s kinda weird to hear people talk about “benefit.” Why we have to go there? I-man reap what he sow. Too much self-centered thing, you know what I mean? Why it have to benefit me more than you, or you more than me? What’s that about?

Q: To be fair, I think Don Carlos –

Garth Dennis: That is what caused the [breakup of Black Uhuru]. People want more than dem share, more than the other person. Which is unjust.

Q: I think Don was saying he was upset with Duckie –

Garth Dennis: [He wanted] Duckie to be more honest –

Q: Because he felt [Duckie] had manipulated the situation.

Garth Dennis: Exactly. That’s what he’s saying. But mi no want to point the finger at anyone, you know?

Q: If you guys could get back together and no one [was treated unfairly], would you do it?

Garth Dennis: Perfect. Perfect. I regrouped with the Wailing Souls more than once; I would regroup [with Black Uhuru] anytime. For the benefit of the music. And what should ever come after that.

Q: After you and Don Carlos separated from Duckie, you guys played together for a long time before Duckie sued over the [Black Uhuru] name. You guys were successfully touring in California and lots of different places. All over the world. Why did you and Don stop touring together?

Garth Dennis: It’s a good question. Good question. You’ll have to ask Don that.

Q: Now you and Don remain close friends, I think, because on your 2015 solo album “Trenchtown 19 3rd Street” – an album which I have a number of questions to ask you about – [Don Carlos] is featured on a very beautiful and conscious song called “Save the Children.” So you must still have a close relationship with Don?

Garth Dennis: Yeah mon. In fact, that particular song [“Save the Children”], that was a Black Uhuru song –

Q: One that was recorded?

Garth Dennis: No. It was about to be recorded but never was because of the disagreements between us. It was written by me. It’s just like the song “Slow Coach.” That [too] was a Black Uhuru song. But that was back [in the days] where if you make a mistake on the record, you have to come back [and record it again]. So the harmony was giving [us] a lot of problem at the time.

Q: When Black Uhuru tried to sing “Slow Coach” — one of your first songs together?

Garth Dennis: Yes. I wrote that song. But when we sing that song, the harmony was giving us a problem. Not pointing no fingers at anyone, but the [least] experienced one was Duckie at the time. And the producer had a flight to catch. So what he did was just lead with my vocals alone. And he release[d] it under my name, [though] it was a Black Uhuru project.

Q: That song “Slow Coach” is such a beautiful song, so relevant even today.

Garth Dennis: Give thanks.

Q: Now [as I alluded to], in February of 2015, after a more than four decade-long career singing with Black Uhuru and Wailing Souls, you released your first solo album “Trenchtown 19 3rd Street.” Why, after such a lengthy, successful career, did you decide to make a solo album?

Garth Dennis: It’s just a vibration, you know? Because after going through the vibrations with the brethren [in Black Uhuru and Wailing Souls], every time I work on a solo album, they approach me, and [we’re] jamming together again. So this time, I [finally] had enough time [on my own]. And I decided to give it a shot.

Q: I think it’s a fantastic album. Why did you name the album “Trenchtown 19 3rd Street”?

Garth Dennis: 19 3rd Street was where The Wailers [were] formed. That’s where Bunny, Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Junior Braithwaite, Cherry [Smith or Green], Beverley [Kelso], and Georgie used to live. [And] that was my home also. And that is why songs [on the album] like “Wondering Now” [are] on it.

Q: That’s that song with your sister –

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: She was part of the popular ska duo in Jamaica [in the 1960s], “Andy and Joey.”

Garth Dennis: Yeah. And [“Wondering Now”] was a big hit before [The Wailers’s hit song] “Simmer Down.” And we were all [growing up] together in that area [in Trenchtown] there.

Q: So you wanted to pay respect to that [neighborhood with your solo album]?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: The album cover is fantastic. I know it was done by Neville Garrick, known for creating the artwork for many of Bob Marley’s album covers. How did that come about?

Garth Dennis: Well, I met Neville a good while ago. His son and my son went to the same high school in Jamaica. So they keep up that friendship.

Q: Your solo album was independently produced on your own “Dennis Dynasty” label. I like the name, and I guess you chose it because eventually you plan on turning it over to your sons?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: And in fact your sons can be heard playing instruments on your solo album, too?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: Your solo album has been out for three years. Overall, are you satisfied with how the album has been received by the reggae listening public?

Garth Dennis: Well I wouldn’t say the “reggae listening public.” Because if you don’t hear it played on the radio, and you don’t [hear about it] in the press, and you don’t get the type of promotion so the public can hear about it –

Q: So you’re not satisfied yet –

Garth Dennis: No, not at all. I wish they could hear [the album] more.

Q: I think it’s a one–of–a–kind album. It’s conscious, it’s rootical, it’s heartical, it’s well-crafted. It’s all of those adjectives and more.

Garth Dennis: Give thanks.

Q: And I was surprised that, despite write-ups [about your solo album] in the [Jamaican] Gleaner and [Jamaica] Observer that mentioned that [master percussionist and producer] Sly Dunbar was heavily involved in this album of yours, that there wasn’t more of a buzz in the news media generally when the album first came out. There are many quality tracks on it. Probably my favorite is that song we discussed, “Save the Children,” which you sing with Don Carlos. There are actually two versions of that song on the album. It’s a moving, sad song about the state of the world. It focuses on both the mistreatment of women and a lack of safe places for children to play. What was the motivation behind this song, and what do you hope people take from it?

Garth Dennis: It’s like – look what’s happening now.

Q: With children being ripped from the arms of their parents at the [U.S.] border?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. And it’s not only at the border. It’s what’s going on [all over]. And the disrespect of women. People need to wake up to save the children.

Q: Two other gems on your solo album are remakes of older songs. There’s “Folk Song” and that song “Wondering Now” with your sister Joan Dennis, known as “Joey.” “Folk Song” is the first song you recorded as a professional. It’s a cover of Curtis Mayfield’s “Romancing the Folk Song.” This song was pressed on the Topcat label in 1972. And like “Slow Coach,” I understand that “Folk Song” was supposed to have been a Black Uhuru song. But because there was again trouble with Duckie laying down the harmonies, you ended up singing it with Don Carlos and Boris Gardiner – who just happened to be in the studio?

Garth Dennis: Right.

Q: Why did you decide to include “Folk Song” on your solo album? Why did you dig back into the past to bring that song [to life again]?

Garth Dennis: Because that’s an original Trenchtown vibration from the early days. Those are [the kind of] songs we use to sing at that time. Curtis Mayfield was very influential to us.

Q: Many of the songs you sang with Black Uhuru and Wailing Souls have emphasized your Rastafarian faith, and your solo album is no different. There are two very melodic tracks on it called “Jah House of Love” and “Eyes Open” (featuring Ras Michael); these songs have powerful, meaningful messages about faith. True?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. Definitely.

Q: Reggae historian Roger Steffens has written that Ras Michael is considered by many to be “the most important Rastafarian musician” in Jamaica. Do you agree?

Garth Dennis: Well you don’t want to point the finger at no one man. Because Jah is in every man. So you have to respect every man. ‘Nuff respect to Ras Michael, but you don’t want to pinpoint any one man, you know what I mean?

Q: Respect, Mr. Dennis, respect. Mr. Dennis, were you a Rasta from youth?

Garth Dennis: I start[ed] off being raised in the Christian church. But when you come to overstand what Rasta is, you realize you’re born a [Rasta]. The thing that they are telling you about [what] you have to seek and find? When you find out about Rasta, you realize, “oh, you are the thing that’s important.” Rasta let you know you don’t have to search for the thing. Because Rasta is here, there, and everywhere.

Q: I understand you lived in the same area as renowned Rastafarian elder Mortimer Planno, who counseled Bob Marley and many others. Did you know Mortimer Planno?

Garth Dennis: Yes, I [did] know Planno. But Bob Marley know about Rastafari before he went to Planno. From when he was around Joe Higgs he know about Rastafari and Selassie. Because on 3rd Street there were a lot of Rasta folks in and around Trenchtown. But Mortimer Planno was a very learned Rasta man.

Q: And Mr. Planno had books about Rastafari and black power in his house, true?

Garth Dennis: Yeah, that’s consciousness you know.

Q: And is that a place where you would go?

Garth Dennis: It was a place I would go frequently; I was accepted there as a young man.

Q: Were you in Jamaica when his Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I visited [Jamaica] in 1966?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. Give thanks. I sure was.

Q: Were you at the airport when Selassie’s plane landed in Jamaica?

Garth Dennis: No, I didn’t go to the airport, but I saw him twice.

Q: How did you see him?

Garth Dennis: I went to the city, to downtown. He passed through and I saw him [as he passed by].

Q: That makes me think of Don Carlos’s song, “Just a Passing Glance.” But Don told me that he didn’t actually see [Selassie] that day; he said the song was written because he caught the vibe of how the people felt. But you actually had that experience of seeing [Selassie] passing by!

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: What street were you on when that happened? Do you remember?

Garth Dennis: I was on King Street.

Q: Nice.

Garth Dennis: And then I was on Spanish Town Road [when I saw H.I.M. pass by again].

Q: What do you remember most about the vibe in Jamaica when Selassie visited?

Garth Dennis: It was glorious. Glorious. Everything was alright.

Q: Now in past interviews you’ve discussed how Joe Higgs, widely regarded as “the godfather of reggae music,” [who, in addition to his own singing success, rehearsed and mentored Bob Marley and the Wailers and many other famous reggae artists such as Black Uhuru, Wailing Souls, etcetera]. I know Joe Higgs was your brother-in-law. And anytime you read into the history of reggae music, you learn what a great and influential man Joe Higgs was. What was it about your brother-in-law that made him such a good singing coach, and leader of young men?

Garth Dennis: He was just a natural person who loved what he did. And he loved to pass it on.

Q: Was it true that Mr. Higgs was a stern teacher?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. At times.

Q: He could be tough?

Garth Dennis: Yes.

Q: He would demand perfection?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: He wouldn’t hesitate to correct you? He would step in and tell you if you were off-key?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: What is the most important lesson he taught you?

Garth Dennis: Responsibility.

Q: In more than just music?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: You used to watch the early Wailers rehearse in your yard in Trenchtown, true?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. I used to rehearse with them too sometimes. See, I know Bob before all of those people. Before Bunny [really]. Before Peter.

Q: How did you meet Bob?

Garth Dennis: I use to live downtown in Kingston city on a street called “Princess Street.” And right across from me on the other side of the road, Bunny [had] a brother and a sister. And [Bob] used to come there. And you know the connection between Bunny’s daddy and Bob’s mom?

Q: Yes. Toddy Livingston and Cedella [Marley]; they had a daughter together.

Garth Dennis: Okay, yeah. That’s how I met Bob. Because Bob used to come around “Princess Street” to visit.

Q: There are not that many people who grew up with Bob Marley who are still alive; what do you remember most about when you were younger and friends with Bob Marley?

Garth Dennis: The oneness and the joy. And that unity he used to bring. Trenchtown was like a heavenly place. Don’t let them fool you, man. Trenchtown was a heavenly place! During rehearsal time. When football was going on. When cricket was going on.

Q: Was Bob Marley a light-hearted and fun guy?

Garth Dennis: Yes! Very much so.

Q: But when it came to the music, he’d be [dead] serious?

Garth Dennis: Yeah. Just like Peter too. If you spend time with Peter, you’re going to laugh a lot, man.

Q: Do you remember seeing Bob getting picked on because he was mixed race? For example, did you hear people call him names like “half-caste” and things like that? Did you see him being picked on because of his skin color?

Garth Dennis: I never hear them use the word “half-caste,” but every now and then he would be picked on in a certain way. But a lot of times it’s just jealousy that does it.

Q: People picked on Bob because he was talented?

Garth Dennis: Sometimes, yeah. But if Bunny is there, that can’t happen. If Bunny is there, they can’t pick on him.

Garth Dennis: Sometimes, yeah. But if Bunny is there, that can’t happen. If Bunny is there, they can’t pick on him.

Q: Because Bunny would step in?

Garth Dennis: Yeah.

Q: Would Peter come to Bob’s defense too?

Garth Dennis: At times. More Bunny.

Q: You were in Jamaica recently to witness Bunny receive a lifetime achievement award from [the radio station] Irie FM, and also, to give a tribute [to Bunny]. Can you tell me a little what you said?

Garth Dennis: I just let them know that Bunny was one of the main foundational artists. And Bunny was the one who a lot of times kept the Wailers together.

Q: How is Bunny Wailer doing these days?

Garth Dennis: Great. Marvelous.

Q: Is he still involved in music?

Garth Dennis: Oh, he’s still involved in music.

Q: In an interview with Roger Steffens, Joe Higgs said: “When Bunny and Bob were growing up together, Bob was not treated as one of the family. He was like an outcast in the house. His mother today comes with this legacy, as if she were there . . . . The mother, Cedella, wouldn’t allow anyone to know he was her son.” You were in Trenchtown at the time and knew Bob. Did you also witness Bob being neglected by his family growing up? What do you know about this?

Garth Dennis: He was a lonely person. I didn’t see any family around him.

Q: Thank you so much for this time, Mr. Dennis. I just want to ask you one more question: Do you think now that you’ve made a solo album, that you’ll continue to make new music and release [yet another] new album?

Garth Dennis: Definitely. But if it comes to a group thing again, I’m ready. Anytime. I’ll never stop making music.

Photos by Stephen A. Cooper unless otherwise noted

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq