Immersed in the Fullness of Half Pint

Half Pint (né Lindon Andrew Roberts) is one of the most famous, gracious, and conscious of the cadre of iconic reggae singers in the world. His songs have been covered by superstars such as The Rolling Stones and Sublime and, whether publicly or privately, and in most cases both, true reggae lovers have on many occasions – at home, in the dancehall, at a party, or wherever – found themselves trying to imitate the inimitable, soulful sound of Half Pint.

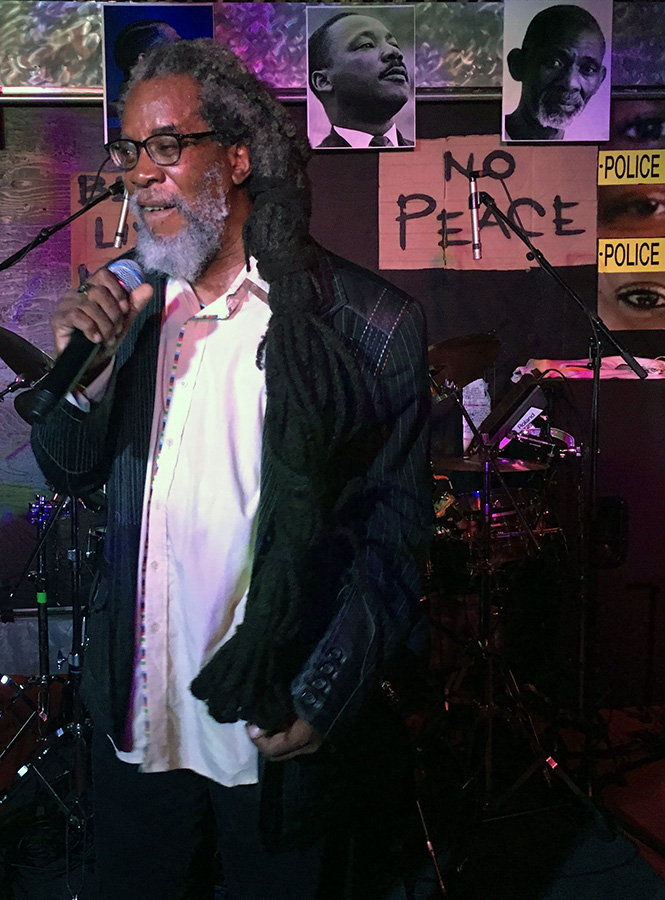

On May 24, after he delivered an energetic, exciting, one-of-a-kind show, and thanks to the assistance of Booking Agent/Tour Manager Robert Oyugi, I was ecstatic and greatly privileged to interview Half Pint behind the Jade Lounge in Monterey, California.

Although it was late and he had to return home to Jamaica the next day, Half Pint and I spoke at length about problems with the stage management at the last Rebel Salute reggae festival in Jamaica; details about his childhood growing up in Jamaica; Rastafari; the sexual misconduct and abuse allegations against Michael Jackson and their effect on Jackson’s legacy; the backstory behind The Rolling Stones and Sublime covering his songs; the Jamaican government’s failure to properly honor some of Jamaica’s most talented and accomplished reggae musicians, and much, much more. What follows is a transcript of the interview, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: So I’ve always wanted to say this: Greetings Half Pint!

Half Pint: (Laughing) Uh-huh.

Q: Thank you for taking the time to do this interview. Have you ever performed in Monterey before?

Half Pint: I think this might be the second time. But it’s a pleasure doing this interview with you right now because these things have to be recorded and set in time. Monterey is the place to be I would say. Monterey is a special place. There’s something about Monterey.

Q: Yes! Jimi Hendrix breaking his guitar here –

Half Pint: Right on!

Q: Now it was just a few months ago Half Pint, in January I believe, that the Jamaica Observer noted that you gave, in their words, “a strong performance at the 2019 Rebel Salute,” Jamaica’s largest annual reggae festival. Now I’m guessing that wasn’t your first time performing at Rebel Salute?

Half Pint: No, I think that was my third time.

Q: There appeared to be some stage management or other operational problems at this last Rebel Salute leading to some abbreviated performances by Jah Cure and Bushman, and the show’s closer, Kenyatta Hill, not getting to perform at all. Publicly, Bushman had some very heated and emotional words about what happened. Do you have any thoughts about [it]?

Half Pint: All I could say is the stage management, it does carry principles. And respect. And time. If each artist has a scheduled time [to perform], that’s how long they should stay on the stage for. But I think some artists overstay their time, and then [their] time runs into other artists’ time [to be onstage]. And then other artists do not get to perform.

Q: Who ultimately bears the responsibility for that? The artists or the persons running the festival?

Half Pint: I would say the persons running the stage – the stage manager.

Q: In your opinion, has Rebel Salute improved over time as far as you’ve seen?

Half Pint: In some aspects. But when it comes to the more technical part, like even the stage presentation, they’re kinda needing more professional service.

Q: Bushman said that he thinks the festival should be extended to three days. Do you also think that?

Half Pint: It could. It could. Because there are a lot of artists from Jamaica who could be performing from a musical standpoint. I hope Rebel Salute will continue to be a special event for Jamaica. And artists who are not publicly seen that often. Rebel Salute tends to find those artists and bring them some exposure. And fresh presentation too, yeah.

Q: Half Pint, I know you were born [in 1961] and grew up in central Kingston – in an area called Kingston 11 near Chancery Lane and near where Joe Gibbs’s and Randy’s Record stores were – but then you also would spend considerable time as a youth in the west Kingston area of Waterhouse. Is that accurate?

Half Pint: Waterhouse is like St. Andrew. West Kingston is more like Kingston, Kingston. Waterhouse is more like up – more like Kingston 11. I was more originated, born and growing up, it was like the central of Kingston itself. Where I was hearing Joe Gibbs’s record store. And Randy’s record store. Across Orange Street. Those two were distinct record stores in Jamaica. In Kingston.

Q: That’s where all the new releases would come, from the U.S. and the U.K.?

Half Pint: From the U.S. and the U.K., and even from in Jamaica at the time. New songs would always come there. And be released. And people could go there and buy them [there]. The freshest or the latest songs, you could get [them] at Joe Gibbs’s or Randy’s.

Q: In past interviews, you’ve always spoken fondly about being raised with very strong values by your mother, but also, particularly by your grandparents.

Half Pint: Right.

Q: In fact, I believe you’ve said that “Sally,” your very first hit single in Jamaica, was really a song where you [are] expressing admiration and yearning for a humble and steady love – like the kind [possessed] by your grandparents. Is that accurate?

Half Pint: Yes.

Q: Now in many interviews you’ve given you’ve identified the church as where you first began to sing. Is this true?

Half Pint: Uh-huh (nodding).

Q: I think you’ve said both yourself and your grandma would sing in the church choir?

Half Pint: Right, right.

Q: Now there have been a number of reggae stars that I’ve interviewed who likewise were raised in a Christian household. And they began singing and receiving their musical foundation from the church, before eventually, usually as they begin adulthood or in their teen-age years, become introduced to the teachings of Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie I. Can you describe a bit how this transformation to Rastafari in your life occurred?

Half Pint: Originally, I would say Marcus Garvey, I learned from him the concept or the understanding of self-preservation and life. Being self-productive. He [taught] us self-reliance. And my grandmother, and my grandfather, their principle ways of life was like that even from a biblical aspect. It’s like they would say: “Every man for themselves, and God for us all.” My grandmother was very churchical. And [also] having that spiritual way of being self-sufficient, too. And give thanks for the little that you may have. And I got those attributes and thoughts from her. And that makes sense to me because growing up, you realize [that] even family values – and parents [are the key]. My father would be going to work. My mother would be going to work. Your life depends on how you work and produce, and provide. So those principles were instilled in me. And I saw much more depths from my grandmother and my grandfather’s characteristics. They gave us [a] certain love [and] certain teachings that was more like the “grand” teachings. Grandma’s teachings were deeper and more accepted. Her hug and her love – it was even more real! (Laughing)

Q: Wow. Wow.

Half Pint: You could know that Grandma love you! (Laughing) When she’d talk to you, she’d talk to you even more distinctly than mama! And you’d hear her even more than mama! (Laughing)

Q: What did your grandparents do for a living? How did they support themselves?

Half Pint: My grandma used to do sewing. Making dresses and clothes and all of that.

Q: And your mom?

Half Pint: She would also do some of that kind of work, in a factory, making shirts and all of that.

Q: What did your mom and grandparents think when you started to read Marcus Garvey and talk about Haile Selassie I? What did they think about that?

Half Pint: The first time I remember my mom – my mom’s perspective. She looked at me like, “Hmm.” [She said:] “What are you gonna tell your children’s teacher? What are you gonna tell the teachers dem about why you become a Rastafarian? And the teachers are gonna be taking your children [away from you] then.” And she was looking at me like, “Oh, your father is Rasta?” And I wasn’t even thinking about it like that. I was just seeing it like: I’m gonna live my life. I’m gonna walk my walk, and talk my talk. My grandmother, when she catch up on me, she wasn’t really surprised. But I could see that she was looking at me deeply one day, and she said: “You really meant it. You know what you’re doing? Or where you’re going?” (Laughing) Her attitude was like that to me. She never shunned me or snubbed me.

Q: So she questioned [your decision to become a Rasta], but she ultimately respected your choice to choose the path you chose?

Half Pint: Yeah. She knew that I was in a sense still Christian-minded. Because after a while Rasta became intertwined with Christianity, too. Originally, when it just began, it was a matter of being more self-sufficient. Being your own provider. Praying to your own God.

Q: And there are different mansions of Rastafari –

Half Pint: Denominations, yeah.

Q: I know that the Twelve Tribes [followers] at least are supposed to read a chapter [of the Bible] each day.

Half Pint: Yeah, yeah. Psalms.

Q: So I see what you mean about [Rasta] being intertwined with Christianity –

Half Pint: Right, right.

Q: I’m not sure if it’s the same for the Nyabinghi mansion [of Rastafari] –

Half Pint: Not altogether, right. But Binghi still know of the Christ. Binghi will say “the black Christ.” They are still corresponding with Christ, the black Christ. And Selassie? He established the Ethiopian Orthodox church in Jamaica.

Q: A somewhat related question I’ve asked reggae stars [before], that have a background [like yours] coming out of a Christian household, is about the decision to choose a non-traditional career path of being a musician. Being an artist as opposed to some traditional [career] path. How did your family respond to that? I know after your secondary education [was complete] that you started singing on the [local] sound systems. You were singing with Black Scorpio, with Mellow Vibes –

Half Pint: Right, [and with] Jammys.

Q: Did your family support [your] decision to follow this musical path? Or did they think it was foolish?

Half Pint: No, I didn’t find it like they were looking at it as foolish. They had known other musical people from before. And I think my mom, she was like, “Ok, you like it like that? You’re like that? Oh, great then. Lucky you. You are a fortunate youth.” She never knocked it altogether. She still gave me that encouragement. She would make me feel like she was encouraging me still.

Q: Cool. Pint, just five months ago you did an interview with a young man who had to have been less than ten years old, Cassius of East Rock Roots. It’s a very good interview available on YouTube. There are [a few] things from that interview I want to follow up on. During the interview you were asked about your biggest musical influences coming up and you highlighted the Jackson 5, specifically Michael Jackson, as having been tremendously influential on you. True?

Half Pint: Yeah. True. He does.

Q: And I think that’s true for many musicians in the world.

Half Pint: Yeah.

Q: But I want to ask, have the many sexual [abuse and] misconduct allegations against Michael Jackson, documented and speculated upon in the press, have they affected the way you feel about Michael Jackson’s musical legacy; can you separate the artist from the art?

Half Pint: I do. I’m conscious about all of the – the news. The things that have been said about him. And the views. I’m conscious about it, and I’m still seeing it like: as light is to day, or truth is to falsehood, or right is to wrong. I’m seeing it like that. Before God and man. And for those who don’t believe in a God, well I’m saying it for those who believe in a God. Because God don’t love ugly. And if all those ugly things have been said is true, I see God to judge him according to his deeds.

Q: So that’s for God to judge?

Half Pint: You see what I’m saying? Because up until now, even now, I’m still concerned: Is it really true? All that has been said? Can it be really, really proven?

Q: Because he was never convicted in a court of law?

Half Pint: Right. That’s what I’m saying. And even then, I used to look at it back in the time and say to myself, wow, I haven’t heard up until now no one gave no consent that they were penetrated. I was like curious about it. Because I was like, wow, should I have to be thinking about that?

Q: So you still have some doubt about it?

Half Pint: Yeah, up until now, I still have some doubt about it.

Q: The other thing that Cassius asked you about – which most people do – is your stage name “Half Pint.” Now you’ve said before that the name “Half Pint” was given to you when you were five or six years old by a man named Mr. Brown –

Half Pint: Right, right.

Q: – and he was the father of one of your mother’s friend’s in Waterhouse –

Half Pint: Right, right.

Q: – and he called you “Half Pint” because even though you were just a little boy, you had a very big I.Q. and ideas.

Half Pint: (Laughing) Yeah, he saw my high I.Q and he gave me that name. You remember Laura Ingalls in “Little House on the Prairie”?

Q: Yeah.

Half Pint: (Laughing) They call her Half Pint, too.

Q: (Laughing) I didn’t know that.

Half Pint: Because she was young and feisty! I wasn’t rude, but I had a lot of thoughts [as a youth]. I could talk to you as a big man, and you’d be like “Whoa, who is this little one!?” (Laughing)

Q: Now, there is a man named Norman Stolzoff who wrote a book about dancehall culture in Jamaica published by Duke University Press in 2000; it’s called “Wake the Town and Tell the People.” In the book, Stolzoff writes, “Frequently DJs just getting started in the business take on names that make reference to their musical fathers (so to speak) . . . . For instance[, he writes,] “Two dub store entertainers – Ninja Ford and “One Pint” took on names that signal their discipleship.” Do you know this artist “One Pint” at all?

Half Pint: No, not really.

Q: Have you ever heard of him or met him?

Half Pint: I think I heard the name but I never met him, no.

Q: So according to [Norman Stolzoff] who wrote this book, this guy One Pint is your disciple.

Half Pint: They intertwine themselves like that to get that attention – or to get that connection.

Q: Have there been others who have called themselves “Pint”?

Half Pint: Yeah, other people too. (Laughing)

Q: One last thing that very effective interviewer Cassius of East Rock Roots raised with you five months ago I want to ask you about; it’s a subject any reputable interviewer would ask you about: The Rolling Stones covering your smash hit song “Winsome.” Their version, of course, is called “Too Rude” with Keith Richards on lead vocals. I believe The Stones put their version out on an album (called “Dirty Works”) just one year after your [original] version [of the song] came out. And you only found out when Jimmy Cliff and percussionist Sydney Wolfe came back from being in Europe –

Half Pint: – and told us about it.

Q: They were in Holland, I think, in a studio with The Stones when Keith Richards chose “Winsome” to cover?

Half Pint: They were in the studio with Keith and them doing the production at the time, yeah.

Q: Now Cassius asked you how you felt about this. And you said, as you have often, that you felt “great” about it. And logically, it makes sense as a young musician as you were, that it would “feel great” to have The Rolling Stones cover your song like they did – and the massive exposure that brought you. But I’m curious whether The Stones were careful to credit and also compensate you for the use of your song economically, in the song writing credits?

Half Pint: Yeah, [my] lawyer worked it out. But I think it could have been worked out better – where the lawyer was concerned. [But] the credits and the rights were there.

Q: But you’re saying that the deal that was made [with The Rolling Stones] by your lawyer at the time could have been better?

Half Pint: Yeah, or [they] probably hide things from me. (Laughing)

Q: (Laughing) Because they’ve made a lot of money off of that song? And you’re wondering where some of that stuff is?

Half Pint: Alright! You better believe. (Laughing)

Q: Now have you ever met Keith Richards, or any of The Rolling Stones?

Half Pint: No, never.

Q: So they’ve never done anything like buy you a dinner? Or a beer?

Half Pint: (Laughing) No, no.

Q: Don’t you think they should?

Half Pint: They could get send me a ticket, maybe!?

Q: (Laughing) A ticket to see one of their shows?

Half Pint: (Laughing) Yeah, send a ticket to me, let me come see one of their shows!

Q: We have to let them know this, Pint. I also wanted to raise the issue of The Stones covering “Winsome” because, while I don’t think this is necessarily true, [Stephen Raphael] wrote for rebelnoise.com: “For years, Americans have been exposed to Half Pint music through the famous bands that have covered his songs.” And because he also wrote, “Sublime is another supergroup that [you] helped strike musical gold.”

Half Pint: Right. Ha-ha!

Q: Of course I’m talking about your song “Loving” which provided the chorus and melody for Sublime’s hit “What I Got.” Now when it comes to their cover, my understanding is that, just like The Rolling Stones, they never approached you about it first or sought [your] permission?

Half Pint: Not altogether.

Q: Did they ever ask you before they did it?

Half Pint: No. No, no, no. My manager was the one to pick up on it. He called their attention [to it].

Q: In fact, there was a news article around that time, that as a result [of what happened with Sublime], BMG Music Group – who was then in charge of your publishing rights – they had to take some steps to go after Sublime to make sure that you could be compensated. Is that what happened?

Half Pint: Yes. Yes, it did.

Q: In 2007 you were quoted [in the press] saying: “It’s important to have proper publishing to take care of your body of work, so that no one can pirate your things.”

Half Pint: Right on.

Q: Relatedly, in 2012, the Jamaica Observer reported you had renewed your five-year contract with publishing company Universal. Is Universal still in control of your publishing rights?

Half Pint: So far, yes. We’re looking into it. I think it will roll over. But I’m learning along the way even up until now. Because some more legal aspects of it need to be taken care of. So I’m having some people look into it right now. But I think [my catalogue] may still be in their license-ship still.

Q: This is critical because it involves the control of not only all of your hit-songs but –

Half Pint: – my catalogue.

Q: – your songs have been used in video games, in ringtones, so all these things are very important for an artist to protect?

Half Pint: Yeah, and capitalize on, definitely. All these things, the government collects taxes for. I’m in the Grand Theft Auto

Q: Is that right?

Half Pint: Yeah, that was one of the biggest ones they sold at the time. Me and a couple other artists [are] on the soundtrack.

Q: Protoje –

Half Pint: Yeah, he’s on it too.

Q: – is on that. Now Pint, recently I had the good fortune to interview Cocoa Tea. And one of the things we discussed is the Jamaican government’s failure to properly recognize and honor many of reggae music’s foundational and legendary performers.

Half Pint: Right.

Q: Cocoa Tea told me he has, in fact, never received any award for his contributions to reggae from anyone in Jamaica. In the United States, I know that you, Half Pint, have been presented with the key to the city of Lauderdale Lakes, Florida, in 2000. And, in 2007, the city of Hartford, Connecticut, honored you with a special proclamation. Now, in 2018, it was reported that you were honored in Jamaica at the “Bob Marley One Love Fun Day Football Matches” along with Barrington Levy and Tony Tuff, at the Harbour View Mini Stadium in St. Andrew. But other than that, have you ever received an award or other official recognition or commendation for all you have done for Jamaican music for over 40 years?

Half Pint: Not – they do recognize me. But to the extent [they do], it’s still minimal.

Q: There are some musicians like Bunny Wailer who has received an Order of Distinction. Also [King of Ska] Derrick Morgan. Has the [Jamaican] government given you some kind of recognition like that that I don’t know about?

Half Pint: No, no, no, no, no.

Q: So when you say that they [the Jamaican government] recognize you, what do you mean?

Half Pint: (Laughing) You got a little segment of the Jamaican music industry which they will recognize [musicians] in their own little way and things. Yes, and it can be recorded or mentioned: When I say minimal? They are like mediocre. You never get much real status like Order of Distinctions [from the Jamaican government]. The highest honors? We [reggae artists] never get those awards.

Q: This has been something in my interviews that I’ve been trying to pursue and understand.

Half Pint: First and foremost, I must say, we are more like folk legends. Or folk heroes. Folk singers and dancers of Jamaica. Which is for a more cultural aspect, real origin from whence we came. So even those things, even those eras and times of our life, [the government] knows them and they recognize them, but they didn’t really give them the proper recognition when those people were alive like back in the 60s and 70s. Like [Jamaican poet and folklorist] Miss Lou [Louise Simone Bennett-Coverly]. Miss Lou get certain attention and recognition, but there were many more like Miss Lou. Because I think [Miss Lou] has an Order of Merit. Or something. But what I’m trying to say is, overall, the whole cultural aspect of our people and our time was never respected in general. So from the music standpoint, or the comedy standpoint, or the athletic standpoint, some of us never get recognized by the government. The few that they give is from a partial perspective, or politics. (Laughing)

Q: And that has been well-documented. One thing that [also] frustrates me, and let me put it out there in blunt terms as a reggae journalist, for example, when I go to interview [the legendary] Derrick Morgan, why is he staying in a small [and dingy] hotel room in Chinatown [in Los Angeles]? Why [isn’t the Jamaican government] contributing to help people who are the icons of reggae to tour and spread this great music [worldwide]? I’m not saying they need to put him up at the Marriott [though they could].

Half Pint: Right on!

Q: But I’m saying, it’s Derrick Morgan[, the King of Ska], and the man [can’t] see. Why is he in some cheap motel in Los Angeles? Why isn’t the Jamaican government contributing more to help this man tour – if he still wants to at his age?

Half Pint: Hey, as I said to you earlier, politics have a lot to do with governance, and in general, it doesn’t really serve down to the common man.

Q: And I know that reggae music is about poor people –

Half Pint: That’s right. That’s why they don’t serve it – don’t respect it.

Q: But at the same time, we can see how much money can be made from reggae. And the government obviously must be able to see this.

Half Pint: Overall, to sum it up, they say, the truth shall set you free. If the music is supposed to be dealt with truthfully, Jamaica overall would be free and more better off in general. And the music speak[s] the truth of the mind of the people.

Q: But they’re not free. And that’s why reggae music will always –

Half Pint: Yeah, the politics will always be against reggae.

Q: And that’s why also reggae will always have something to say.

Half Pint: (Laughing) The people’s voice, [it] really comes from the music, mainly.

Q: Just a few last questions, Half Pint, and thank you again for this time. You have so many massive, legendary hit songs. But for myself personally, and I think for many others too, [your] song “Greetings” comes to mind immediately when anyone says “Half Pint.”

Half Pint: It’s a signature song of mine, yeah.

Q: Now I know you discussed recording “Greetings” recently, just in February, with DJ 745 from England [for Reggaeville.com]. He came to Jamaica for “Reggae Month,” and he interviewed you in Jamaica, DJ 745. When he interviewed you, in addition to noting as you have before how “Greetings” was recorded in one take, you said you were able to channel so much feeling into the song because you were really “channeling the poor people of the world.” True?

Half Pint: Yeah, it was like that, right. Because I was in London, [and] I saw the economy was taking place just like back in Jamaica. Because in Jamaica in 1985, 1984-1985 we had a little mini-recession in Jamaica. And I think America was going through a somewhat similar time, too. So I was in London and I saw the same kind of toughness, the same kind of struggle. And I was like, whoa, see, people [are] suffering worldwide. And the full impact [of that epiphany] just came out in my voice.

Q: Did you write the lyrics to the song that same day you recorded it?

Half Pint: Yes, in the studio. The very same morning.

Q: Do you remember this morning? Did you stop somewhere, get some coffee, and go to the studio?

Half Pint: No. We had [coffee] before we headed to the studio at home – [at] the apartment that we were in in London.

Q: Who were you with?

Half Pint: Me and [producer] George Phang. And [when we got to the studio,] I said, “put on the tape on the machine.” And he put on the tape on the machine. And that riddim was the first riddim that was on the tape. And I said, “Let that one roll.” This was in the studio by the title of “TMC,” somewhere around Stockwell, in London. It was just me and [George Phang] and the engineer, “Andy.” I think actually when [Andy] heard the song in the morning, he overdubbed his lead guitar [onto the track]. (Laughing) He played the note of the bass line. Because the bass line of that song itself was like: “dubbo-dubbo-dubbo-dubbo.” So the lead guitar that Andy played was similar to the bass line note also, too: “diggy-diggy-diggy-diggy.” And give it that kick too about it, yeah.

Q: Did you show George or Andy the lyrics to the song after you wrote it, [but] before you got up to the mic and voiced it?

Half Pint: No. I just get up to the mic, stand up and sing it out of my brain and my heart and my mind. I didn’t even write it out.

Q: Oh wow! You didn’t even write down the lyrics on a pad or anything? You just sang them?

Half Pint: Back in the days, that’s how we used to do it. Even in the dancehall. We just take the mic, and start singing. We were like that. All those songs that I recorded [in the 80s] –

Q: “Sally,” [“Winsome,” etcetera,] you sang them in the dancehall first?

Half Pint: Yeah, live and direct.

Q: Nowadays people don’t do that as much –

Half Pint: No more.

Q: Do you think the music suffers as a result, because [artists] don’t test their material in the dancehall?

Half Pint: It can. Because when you’re creating on the spot, it is more spontaneous and [it has] more life and more trueness to it. You don’t go back and carve out words and style [or] polish it up.

Q: When you finished singing that one take of “Greetings,” what happened in the studio? What did George and Andy do? What did they say to you?

Half Pint: I think George was like, “Huh.” He didn’t say as much. But Andy, the engineer, he knew this was a hit. And he ran for his guitar and said, “Let me put it on there.”

Q: (Laughing) Let me get my [guitar] on there, too! I want to make sure I am on this [hit song], too!

Half Pint: (Laughing) Yeah, yeah. He showed me that this song had potential, a feel, a vibe.

Q: In 2012 you did an interview in Europe, and you said you thought both the corruption and drug trade were “peaking” in Jamaica. Now, seven years later, is it still like your song “Political Fiction” in Jamaica, is it still a “pity inna di city”? Or do you think the political and social situation has improved?

Half Pint: The political rivalry and confrontation is dying out. But the quality [of] the governance is not that pleasant. The people [need] more social development, [and] the people [need] more work.

Q: Half Pint, is there [anything else] you want your fans around the world to know about your music, or anything [else]?

Half Pint: All I would say [is]: All the fans that I know all over the world, and from the time I started singing, I pray they all stick with me until (singing) “the twelve of never.” Because I’m devoted to them. My duty is to be loyal to all my fans. And I pray and hope that all my fans will be loyal to me. I pray that even their children’s children can catch up and say: “Oh, he was one of the singers of the time. My grandmother and my grandfather used to listen to his songs!”

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq

Steve is the best reggae interviewer around. Hands down. Not afraid to ask tough questions.