Safeguarding Bob Marley with “So Much Things to Say”

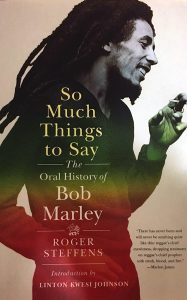

In reviewing Roger Steffens’s latest book, So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley, Hua Hsu asserts in The New Yorker that Steffens’s contribution to the Marley canon is his “nerdish monomania.” But Steffens, who invited me to tour his overstuffed “Reggae Archives” in L.A., epitomizes cool – as does his magnum opus on Marley – right down to its subtle red, green, and gold binding. Moreover, it is Steffens’s avidity and accuracy that allow readers to “really know the man” as Steffens did when he toured with Marley, subsequently devoting his life to safeguarding his legacy. Jamaican poet laureate Linton Kwesi Johnson writes in his introduction to Steffens’s oeuvre, that Steffens shows “how serious Marley was about his art: his single-mindedness and his consummate professionalism.” Steffens’s book exudes those same qualities.

On July 29, 2017, Steffens blessed me with a return invitation to the Reggae Archives to interview him. The topics we discussed included what got him interested in reggae; how his passion for the music developed; The New Yorker’s review of his new book; the book’s main dramas and themes; and finally, Steffens’s hopes for “So Much Things to Say”’s enduring legacy. What follows is a transcription of our discussion modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Where were you born?

Steffens: Brooklyn. I’m an all-American boy from Brooklyn. I tell my Rasta friends not to mess with me because I was born in Zion. I was born in a Jewish hospital called “Israel Zion” hospital. So, Rasta don’t mess with me. I’m from Zion (laughing).

Steffens: Brooklyn. I’m an all-American boy from Brooklyn. I tell my Rasta friends not to mess with me because I was born in Zion. I was born in a Jewish hospital called “Israel Zion” hospital. So, Rasta don’t mess with me. I’m from Zion (laughing).

Q: What was your pursuit before you got involved in reggae?

Steffens: It was poetry. And drama. I’m a trained Shakespearean actor. I started acting when I was five years of age. I’ve always been involved in the stage.

Q: What got you interested in reggae music initially?

Steffens: There were two strains that brought me to reggae. One was my love of doo-wop – the harmonies. And the other was the conscious music of Dylan and the folk movement in the sixties. The music pretty much died around ’70 and ’71. The last great sixties album was really [Marvin Gaye’s] “What’s Going On.” After that, the little companies were all bought up by conglomerates. And so, they emasculated the music. It was disco – and crap. And I was looking for something to reignite my passion for music. So, in 1973, [when I was thirty-one years old], I heard “Catch a Fire” and saw Perry Henzell’s “The Harder They Come.” And it was different than anything I had ever experienced in my life. I couldn’t believe this huge culture existed just below the United States. How did I miss it all those years!? Where was I? So, that was the major eye-opener. And being in a place that had a lot of imports from England on the Trojan [Records] label. And a record store in San Francisco, [on Filmore Street,] called Trench Town Records, that brought 7 inch singles up from Kingston. And brought Count Ossie and the Mystic Revelation of Rastafari – their “Grounation” album. Ruel Mills, who ran the store, was an old friend of Bob’s. He opened my eyes. He taught me a hell of a lot [about reggae music] in the initial stages.

Q: And you really got into it then?

Steffens: Totally got into it. And I couldn’t wait to go to Jamaica to find all these records –

Q: Because you couldn’t find some of these records where you were?

Steffens: No. British imports and Tower Records and other Berkeley record stores, you could find some English pressings of reggae. And the “Tighten Up” series, which taught me that ninety percent of reggae was crap. And so, I needed somebody to guide me to the real stuff – Alton Ellis, Desmond Dekker, Techniques, and all the rocksteady [artists], Ras Michael….

Q: Notwithstanding that you suddenly had this great passion for reggae, and you fell in love with it, did anyone, like your wife or other family members, say “Hey, Roger, we understand you love reggae, but maybe you shouldn’t go to Jamaica looking for records during one of the country’s most dangerous, most tumultuous periods?”

Steffens: We arrived the week [Michael] Manley declared the state of emergency. An imminent invasion was about to take place. And he was right, in fact. Many years later, Phillip Agee, the renegade CIA agent … You know, Phillip Agee? He eventually fled to Havana and lived the rest of his life under the protection of Castro. And so, that whole period was one of revelation and I wanted to get to the roots. So, when we arrived in Jamaica, everybody said for God’s sake, don’t go to Kingston! They’re killing people on the streets. But, I said, you know I’ve come all this way. I’d saved $400 up to go buy records. I have to go to Kingston, I said! And as soon as we arrived, one of the biggest reggae stars at the time picked my pocket in Bob Marley’s record shack.

Q: You mention that in your new book, but then you never tell who it was…?

Q: You mention that in your new book, but then you never tell who it was…?

Steffens: It wouldn’t be smart for me. I’ll tell you later (laughing).

Q: I have a few questions about the review of your new book by Hua Hsu that appeared in the July 24 issue of The New Yorker. Did Hua Hsu ever come here, to visit your Reggae Archives?

Steffens: No. I’m told he’s an English Professor at Vassar. I guess my publicist may have sent him the book. Just the very idea that The New Yorker devoted six pages to my book is so mind-blowing to me.

Q: You must have felt good about that?

Steffens: Oh, better than good. I was levitating (laughing). And, did I tell you I was invited to read my book at The Library of Congress?

Q: No! That’s awesome! When?

Steffens: Sometime in November. November 2nd, I think. They just asked me yesterday, so the date hasn’t been finalized. So, I mean, anyways, The New Yorker, the Library of Congress….Jesus!

Q: It’s such a big feather in your cap, Roger. Congratulations man! Now, there were one or two things that seemed a bit off about Hua Hsu’s review of your book I want to ask you about. One of Hsu’s assertions is that “the book’s drama accumulates around the question of what set Marley apart from his bandmates Livingston and Tosh.” Do you agree with that?

Steffens: Well, there was a certain amount of drama. I think he has a point there. The fact that at the height of [The Wailers’s] breakthrough they just couldn’t stay together anymore. It’s kind of sad. And I was very angry for many years that Chris Blackwell seemed to almost take joy in the fact that he broke The Wailers up. But, at the same time, what happened is, he gave us three times the amount of music we would have had otherwise. It was like the Beatles. They were all capable of being leaders. And a lot of the Bunny and Peter songs didn’t get a chance to manifest because mostly the songs were Bob’s that were on the albums. It was time for them to make their step. We never would have had [Bunny Wailer’s] “Blackheart Man,” we never would have had [Peter Tosh’s] “Equal Rights” if they had stayed together.

Q: What was most convincing to me, similar to what you said about The Beatles, is the quotation in your book from Bob Marley’s former manager, Danny Sims. Sims said, “Bob had a style, a charisma, and was the obvious superstar. But, you could tell in that setup, all three of those guys were superstars.” Amazingly, blessedly, they just managed to coalesce on this small island of Jamaica. And they got together in Trench Town with Joe Higgs, the Wailers’s first teacher – a legend himself. It was just amazing that you had such a confluence of strong personalities. And talents! Now, I brought up Hsu’s assertion about the book’s central drama because while I found the differences between Bob, Peter and Bunny was certainly one of the book’s dramas, I thought there were many dramas in the book about Bob’s life that were presented. Dramas that potential readers of your book might want to know about concerning Bob’s early life and career; conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination attempt; how Bob developed his health issues and the treatment of them; and the personal dramas that Bob had within his family, with women, and more. In my opinion, the best parts of the book are the concentration on what made Bob such a great artist – what his process was. On his discipline. And, his professionalism. One of the first reggae stars I interviewed was David Hinds, lead singer of Steel Pulse. And, during that interview, Hinds spoke specifically about how he missed Bob’s professionalism and his discipline. And throughout your book, there are passages where people in Bob’s life are also quoted about how Bob was a perfectionist. How he made them be better at what they did. How he made them explore things and challenge themselves. To come out of their comfort zone. Such as when Bob encouraged his art director Neville Garrick to not just do art, but to get into music. Or, how Bob would always be off in some corner alone, practicing; strumming his guitar off to the side. Always, he’d be working. Sometimes in the studio without the band, he’d be working. Those are the parts of your book that move me the most. They explain the makings of creative genius.

Steffens: Yeah. I wanted [the book] to supplant Timothy White’s book [on Bob Marley, “Catch a Fire”]. Because it’s such a flawed book. All those made up conversations just bugged the hell out of most of the people I know who read that book. How did he know what Rita and Bob whispered in each other’s ear when they were making love on the backdoor? That was just so wrong, you know? And he raced through the last four years of Bob’s life as if he was under deadline. There’s very little [in White’s book] about Bob’s last years.

Q: Also, your book, unlike White’s, presents primary source material. Your book is a collage of over 75 interviews you’ve curated of the people who were there, who know firsthand about Bob Marley’s life and career.

Steffens: Yeah. I love Kwame Dawes’s quote [about the book]. Dawes is an amazing actor and poet. Incredibly respected guy. He’s half Ghanaian and half Jamaican. Raised in Kingston. He said, “[t]he book is a triumph of the storytelling virtuosity of Jamaican people.” I wanted this book to be something Jamaican people could be proud of. And to keep my voice out of it as much as possible. Everything I do in reggae comes from one specific point of view. I’m a lucky fan who got on the inside. So, I want to carry that kind of consciousness into everything that I do in reggae. What would you do if you were the biggest Beatles fan in the world and John Lennon said, “come on the road with me?” That’s the equivalent of what happened to me [with Bob Marley]. And so, I write as honestly as I can. And, as passionately and as enthusiastically as I can.

Q: At the beginning of your book you quote an old Jamaican folk saying: “There are no facts in Jamaica, only versions.” And Jamaican music is so much about versions. Putting a different and unique spin on a song, a different take. So, I liked that you begin the book with that quote. Additionally, you cite to and quote so many different characters in Bob’s life – all these people that we are introduced to in the book, the central people in Bob Marley’s life – and they all sometimes have different versions about how things went down. Hua Hsu said in his review that when you, Roger Steffens, show up in the book, that you’re mostly there to “direct traffic.” Linton Kwesi Johnson says something similar in his introduction, that you don’t allow your voice to dominate. Mostly, I agree with their assessment. But, I do think there is a crafty editing that’s being done. And, when you are really trying to get to the truth of a nugget about Bob Marley’s life, you’ve structured the book so you can see when someone’s version is b.s. –

Steffens: Without having to say anything. Discretion, Stephen, is the better part of valor. Every time.

Q: Roger, you have such a wealth of knowledge when it comes to Bob Marley, but also all of reggae music. What are the top four or five non-Bob Marley albums that every reggae fan should have in their collection?

Steffens: “Blackheart Man” by Bunny Wailer. “Black Woman” by Judy Mowatt. “Right Time” by The Mighty Diamonds. “Two Sevens Clash” by Culture. “A Song” by Pablo Moses. Any Alton Ellis or Coxson [Dodd, Studio One] album – they get repackaged in so many ways. Johnny Osbourne’s “Truths and Rights.” “Bobby Bobylon” by Freddie McGregor.

Q: Can you say what your top two favorite Bob Marley songs are? And why?

Steffens: “Waiting In Vain.” Because it’s one of the most beautiful love songs ever written. Linton Kwesi Johnson says it is the most beautiful love song. And also, because it’s the song that got me introduced to Bob. So, it has emotional resonance for me.

Q: Is that when you walked up and congratulated Junior Marvin for his guitar solo – during that song – before one of Bob Marley’s shows?

Steffens: Yeah. And, he took me backstage to meet Bob [for the first time]. I also love the “Time Will Tell” that’s on the soundtrack with from the Countryman album which is a whole different take – much more mysterious and haunting.

Q: You give thanks in your book to Mutabaruka and his efforts to help you relocate your Reggae Archives [containing a massive collection of reggae music and artifacts, including the world’s largest collection of Bob Marley material] to Jamaica. Can you speak more about that?

Steffens: Mutabaruka is a major broadcaster down in Jamaica. He’s got two weekly shows the whole island listens to. He’s a dub poet as Linton Kwesi Johnson is. Very deep, deep voice. Very provocative. Very intelligent. He’s a major figure in Jamaica. He’s been a major backer [of moving Steffens’s Reggae Archives to Jamaica]. I was on the air with him last fall. He’s calling fire and brimstone on the Jamaican authorities who don’t have the intelligence to see how important this collection could be to Jamaica. And how much money they could be making off of it. The Marley family has offered to buy it several times, but all they want is the Marley stuff.

Q: By the way, I really like the picture you chose for your book’s cover. It shows, as you discuss in the book, that though Bob was dealing with many trials and tribulations, and strife, he still had a joy for life. You can see that in his smile on the cover of your book’s jacket.

Steffens: That was the only time in the hour-long press conference in the San Diego Sports Arena dressing room on November 24th, 1979, that Bob smiled. Every flashbulb in the place went off at once.

Photos by Stephen Cooper at the Reggae Archives

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq