Newsflash: It’s okay to be different

I’ve never seen an episode of The Walking Dead, Girls, or The Mindy Project. I watch television very intentionally, because — like many in my generation — I only watch it on a laptop screen. (With that said, I admit to watching mostly talk shows and clips of utter trash.) The Kindle my cousin gave me for Christmas this year is my avenue to publications like The Atlantic and The Washington Post, and I got a subscription to Vanity Fair as a birthday present. On top of that, I grew up with an abnormal level of exposure to Shirley Temple films and Glenn Miller orchestration due to my adoptive mom being a product of the 1930s.

I saw my first Adam Sandler film when I was in the fourth grade, and it was like watching porn. I loved it way more than anyone should love an Adam Sandler film — because it was different from the film collection in my home. And it meant I could have a conversation with someone under the age of forty without developing an ulcer from the stress of trying to build common ground out of Woody Woodpecker laugh impressions, C.S. Lewis quotes, and extremely uncool music and pop culture references.

But growing up with a different perspective, and living with limited exposure to the defining entertainment of this “era” doesn’t necessarily equal a lesser experience. In some ways, I feel like I now choose to live under a rock to continue some semblance of my past (less deliberate) social-emotional quarantine from normal members of society within my relative age bracket.

For instance, I think fondly of the time everyone in my workplace was joking about how certain coworkers reminded them of characters from The Office, and I replied, “I’ve never seen that.” (The looks of pity prompted a 2-year binge-watching of the DVDs with my boyfriend at the time. Dwight Schrute may or may not be my hero.) But that feeling of not really getting it? I guess that’s how people in my high school felt when I referenced re-runs of Growing Pains, All in the Family, and my irrational affinity/crush on the Reagan-conservative Alex Keaton from Family Ties.

Disney movies, Marvel comics and the Lord of the Rings trilogy basically saved my social life. It didn’t connect me to the cool kids, but it connected me to a few kids, and I knew we all generally enjoyed each other’s company.

Feeling different can be isolating if you let it — or it can be liberating. There’s something incredibly rebellious about saying, “Oh yeah? Who cares?” when someone gives you an eye roll or incredulously asks, “You mean you’ve never _____?” Nope. Or Yup. It doesn’t matter.

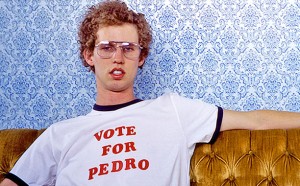

(New Line Cinema)

Connecting with people based on what you like only because everyone “likes” it doesn’t seem like the smartest route to lasting friendships. It’s bad enough to only have interests in common, but to have common interests that are, well, common is just a bore. That mentality makes about as much sense as being friends with someone because they have a hangnail on the same finger as you. You’re just hangnail friends, bound by a temporary condition you didn’t particularly choose. You simply got caught up in the moment.

Or the fad. Or the minor health irritant. Whatever the case, having a unique perspective on the media, politics, religion, or even music may set you apart for a time, but in the end it makes it easier to realize when you actually have something significant in common.

Think about it for a moment: If you have an argument about Sanders versus Clinton, or whether Tom Brady is a dirty cheat, or if Bruno Mars deserves more recognition than Adele, your true friend isn’t going to shun you. Friends are above different, because friendship is bigger than minute and inconsequential differences in opinion. (Yes, opinion. Although I often assert my musical taste as “factual.”)

It’s precisely the people who don’t care what you like or who you like who like you, and who are likable. Because they’re real. They’re different.

And it’s not just okay to be different; it’s the new fitting in.

Top photo: Yoda, Happy Gilmore and Alex Keaton as figures of liberation.

Megan Wallin is a young writer with a background in the social sciences and an interest in seeking the extraordinary in the mundane. A Seattle native, she finds complaining about the constant drizzle and overabundance of Starbucks coffee therapeutic. With varied work experiences as a residential counselor, preprimary educator, musician, writing tutor and college newspaper reporter/editor, Megan is thrilled to offer a unique perspective through writing, research and open dialogue.