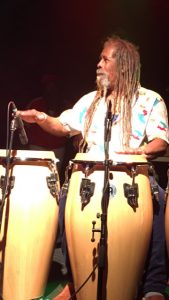

Larry McDonald is “Fattening the Pulse of the Rhythm”

If you’re a music lover the only thing better than interviewing Larry McDonald, one of the best percussionists in the world, is interviewing him twice. With more than fifty years of hand-drumming experience – congas primarily – for superstar performers in reggae, jazz, blues, and beyond (including Bob Marley, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, Taj Mahal, Gil Scott-Heron, and more), McDonald’s accumulated knowledge, experience, and worldly wisdom are unparalleled.

What follows is a transcription of my second extensive interview of McDonald, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations. It was conducted immediately after his October 17 performance alongside Scratch and Subatomic Sound System at the Dub Club in Los Angeles, and, continued, a few days later, during a very enjoyable phone call.

The topics we discussed included: plans for a sequel to McDonald’s highly acclaimed 2009 album “Drumquestra”; McDonald’s longtime friendship with Steel Pulse keyboardist and producer Sidney Mills; the massive impact of Scratch’s “Blackboard Jungle Dub” album; McDonald’s time playing at Scratch’s Black Ark Studio; Joe Higgs’s influence on reggae and how Higgs doesn’t get enough credit; differences in touring and reggae audiences now that McDonald is in his 80s as compared to when he was in his 30s; changes in McDonald’s style and approach to drumming over the years; and much, much more. Enjoy!

Q: Larry, it’s great to see you. Wicked show tonight, congratulations! It’s almost [been] a full year since I saw you last, right here, at the Dub Club [in Los Angeles]. How’s this last year been for you? What [was] the best part?

Larry McDonald: Wow, I wasn’t keeping track.

Q: Just off of the top of the dome. What was [a] highlight?

Larry McDonald: Well, a highlight was [the magazine] Modern Drummer called me and did an interview and sent a photographer; the whole nine. I thought that was pretty cool. It hasn’t come out yet. It was recent. Maybe [it’ll be out] in December.

Q: Cool. We’ll [all] be on the lookout for that. Now last time I saw you, you mentioned that in addition to playing with Scratch, you were jamming with the New York City Ska Orchestra, and [also,] that you were seriously considering a [sequel] to your masterpiece debut [album], “Drumquestra.” Is that still the plan?

Larry McDonald: Yes. It’s still the plan. And I’m putting together material. [So] I’m in the process of ignoring [other] sh*t to do the stuff as I see it.

Q: Are you going to work with [veteran producer and longtime keyboardist for Steel Pulse] Sidney Mills again?

Larry McDonald: Probably. Yeah. We go back a [long time]. Sidney is one of my kids.

Q: When you say that, what do you mean?

Larry McDonald: When I met Sidney, he was a young guy, he was with a group called “Calabash,” and he was working out of HC&F Studio in Freeport[, a town just outside of New York City]. Everybody recorded something [at HC&F]. If they didn’t lay tracks there, it was mixed there, it was voiced there, [or] it was overdubbed there. That’s how it was. I think Shaggy’s first hit came out of there. A bunch of people [had hits] they made out there. So Sidney was like one of my kids. I used to do a lot of production work [at HC&F], you know? Sidney was the keyboard player I used. A lot.

Q: Cool.

Larry McDonald: Yeah. We became tight, you know? And I’d make him play stuff that he wouldn’t necessarily have played if I didn’t want it, you know? (Laughing).

Q: So you’d challenge [Sidney] musically?

Larry McDonald: Yeah. But it was just like expanding his horizon[s], you know? Like if I was doing a tune or something that was out of context, not in the idiom or whatever, I’d get it played [at HC&F Studio with Sidney]. Sidney hadn’t linked up with Steel Pulse yet, you know? So we were all just musicians in the pool. And I was somewhat older than most of them. So, you know, we became pretty close. And because of doing that early work up there, Sidney knows how I think. And pretty much what I’d go for, you know? Like when I was doing [Drumquestra], I needed to be off from time to time dealing with some stuff when I should [have] be[en], strictly speaking, in the studio. But there was other stuff I was contracted to do. And I could leave [Sidney] to do [everything in the studio himself]. [But,] a couple of the tunes I [probably should] have been there for. But they were rescued. Like the tune “Got Jazz.” The one that Bob Andy sang? I wasn’t there that day [in the studio]. But with Bob and Sidney [together], I knew everything would be cool. I mean how far could they go off of the thing, you know? (Laughing). So we did it. And then we came back to New York and Sidney and I listened to it. And I was like, “Where’s the bridge? We can’t put this out without the bridge.” Because originally, I’d written it as an instrumental. So [Sidney] said, “If the bridge is going on it, you’re going to have to sing it, because we can’t bring Bob Andy [to New York] from Jamaica.” (Laughing.) Yeah, so, I did that. And there’s another one that I used my voice –

Q: I didn’t know you could sing, Larry.

Larry McDonald: I didn’t either. (Laughing.)

Q: (Laughing) That’s hilarious. What track is that again?

Larry McDonald: Got Jazz. And there’s another one, “Mento In 3.” And that’s the track where I used my voice as the bass. And [Sidney] insisted that I do each segment of it, right? I couldn’t do like 16 of them perfect and just fly it in. I had to do every last one of them. Look, I guess that’s why you get a producer, okay? So I’m finished now. So I said to [Sidney], “you sure we’re finished in there?” And he said, “Yeah man, I got everything that I want.” And I said, “I’m glad [because] I’m not going back in there [again].” And he said, “Well that’s really the payback, you know?” I said, “Payback for what!?” He said, “All those nights we were pulling all-nighters at HC&F [Studio], and I had to sleep under the piano because I couldn’t get back to Brooklyn. And I’m tired the next day.” And so he said, “That’s a little bit of payback. Just so you know.” (Laughing.)

Q: (Laughing) I’m glad I asked. Because I thought it was significant when you decided to put out your debut album – after more than four decades – that you chose to work with Sidney [Mills] as your producer; that [struck me] as a significant [decision]. That’s why I wanted to explore your relationship with him a bit more.

Larry McDonald: We’ve got that junior—senior thing going on, you know? He keeps my nose in the stuff that’s happening out there now. And I ground him in the history and the foundation.

Q: Larry, when you and Scratch were last in town with Subatomic Sound System, you were promoting the “Super Ape Returns to Conquer” album. But this tour is focused more on “Blackboard Jungle Dub” [overwhelmingly credited as the first dub album ever]. Now I know you were heavily involved in a lot of the music Scratch made at [his] famous Black Ark Studio; did you also play on the original Blackboard Jungle Dub [in 1973]?

Larry McDonald: See, when I use to go there, I never used to hear who the featured artist was. There was a track, and they wanted me to play on the track. So I played on the track. And it might end up on Max Romeo’s record, [or] it might end up on Bob [Marley]’s record –

Q: Scratch wouldn’t necessarily let you know if your [work] was on [a particular] record?

Larry McDonald: No, well, you weren’t about to ask him [back then] – you’ve got to cut the session, you know? And I’d go in and do some stuff. And I’d leave. I’d get some money the next time I come back. You see, it was at a time when my [percussion] was suspect even to me. I’d get the odd recording session and all of that. But I was just one of the cats trying to make it. I was trying to find out what I wanted to say musically, you know? Because that was still early in my [career]. [And] no matter what I wanted to play, [Scratch] was down with it. Because he liked all that odd stuff. Basically, to this day, producers don’t really know what to do with the percussionist when it comes to reggae. Because they’re not familiar with them like they are with the guitar players. Or the bass players. Or the keyboard players. Or the horn players. And the percussionist has too much autonomy. They really can’t tell you what to play. They can tell you what they’re thinking. And you try to match it. But it’s usually part of something that you just play that they like. And they want to hear more of that, you know? So I learned early to say, “Okay, fine.” And then, pretty much do what the tune needed or wanted, you know? The tune makes me want to do stuff, and then I do it, you know? I do stuff that they want, and then I beg for another track.

Q: But do you know [now] whether any of your drums [can be] heard on [the] Blackboard Jungle Dub [album]? Is it possible and [you] just don’t know?

Larry McDonald: It might not be drums, it might be hand-percussion. The thing is I don’t like to claim stuff. Because there were other percussionists around [the Black Ark at that time too]: There was Sticky [Uziah Thompson]. Scully [Noel Simms]. My partner, Denzel Laing.

Q: Can you say [that last] name again?

Larry McDonald: Laing. L-A-I-N-G. We had a couple of minor hits together. And so, [since] people tend to think I was the only one [playing percussion for Lee Scratch Perry at the Black Ark], I’m not quick to claim stuff.

Q: When you first heard the Blackboard Jungle Dub in 1973, from the first track to the last, what was your reaction to it?

Larry McDonald: It was like all this sh*t together in one place. Nobody had heard anything like that [before] –

Q: When you say that, do you mean it was like a blueprint?

Larry McDonald: It’s like – nobody had heard stuff like that. Neither produced like that, nor presented like that. Okay, there are still Jamaicans today who can’t stand reggae. But I’m saying, forget all that, this was the sh*t when it came out! See, actually, the music gotta fight. People tried to put it down. It was too sadistic –

Q: When you say people were [putting the music down], who in Jamaica was doing that?

Larry McDonald: There was a segment of the population. And I can’t imagine [it], but there are still people in Jamaica who are not too keen on reggae, you know? [But] [t]hey come out of the country and they claim it, you know? Since that’s [one] of the only things people know [about Jamaica and Jamaicans].

Q: How involved was [legendary Jamaican producer] King Tubby in the final product that is the Blackboard Jungle Dub, if you know?

Larry McDonald: I don’t know. Who would know is my brother’s brother-in-law, Philip Smart. But Philip died [in 2014]. Philip was a student of King Tubby. Maybe Scientist [née Hopeton Overton Brown, another King Tubby protégé and a legendary producer in his own right,] would know.

Q: Ok. [Scientist] is [definitely] on my list of [reggae music stars, producers, industry insiders, etcetera] to [try and interview] at some point. Now Larry, there really aren’t that many musicians or singers around who cut their teeth at the Black Ark like you did before it burned down. [And] many people rightly believe that the music coming out of the Black Ark in the 1970s represented a “golden age” of sorts for reggae music. What do you think about when you remember the Black Ark during your time there playing the drums for Scratch?

Larry McDonald: Scratch [is] not like any other person. Whatever struck his fancy, he would put that sh*t on the tape. I don’t care what it was. If he liked, it goes on a track.

Q: All kinds of sounds?

Larry McDonald: Yeah. Natural sounds. Unusual sounds. Original. From a four-track [recorder] and shit. (Laughing.)

Q: When you think back to the Black Ark, what do you remember it physically looking like when you walked in there? What do you remember about that?

Larry McDonald: Wow. I couldn’t paint a picture because a lot of the stuff is so nebulous, you know?

Q: Because Scratch had a lot of knick-knacks, talismans, artwork[, and other keepsakes] everywhere? [At least,] [t]hat’s what I’ve read about it.

Larry McDonald: It was pretty much all of that. He still does that stuff on stage with the candles and the incense and all that. To me, it was just Lee, right? The thing is, I wasn’t even thinking about that. What I was thinking about is, look, I was actually getting to play stuff on Scratch’s record[s]. I had a tremendous amount of respect for Scratch. Mostly because other people put him down. But Scratch to this day knows what the fu*k he’s doing, okay? I let people say what they want, and I don’t get in that discussion. [But] [a]t that stage in my career, anyone who wanted me to play anything was cool with me. So I’m going into [the Black Ark Studio] to play. I was concentrating on the fact that I got the freaking chance to play. [I was] insecure, the whole thing, call it what you want. At that time, I was focusing on getting into any type of playing circumstance that I could. When I wasn’t on the bandstand, I was practicing. So that made me good enough that I could keep a situation if I got into it. I needed to be good enough to hold [a] gig.

Q: Larry this next question comes from one of your old friends, Nan Lewis –

Larry McDonald: (Laughing) Oh Nancy!

Q: – who has been promoting reggae music for over three decades and is the booking agent for [veteran reggae artist] Ras Midas: Not necessarily limited to your time playing at the Black Ark, but throughout the 50 years or so that you’ve been around professional reggae musicians [and singers], are there any recording sessions that will always stand out in your memory? Either because they were crazy funny or “wickedly” just perfect from start to finish, the old “one take” recording session way?

Larry McDonald: First of all, all of those early sessions were one take. They were mono, they had to be one take.

Q: But because of that, were there any sessions where someone just came in [the studio] and nailed it, and you were like, wow, I can’t believe what I just saw and heard?

Larry McDonald: You never remember this stuff when you want to bring it up. I’ll say, oh sh*t, I have to call Steve and tell him this stuff. (Laughing.)

Q: You have my number! We communicate. [And] [y]ou’re better than my mom. My mom doesn’t even text. You do text-messaging – which is awesome. Larry, because you’ve worked with so many artists over all these years, are there one or two reggae artists, singers and/or musicians that, for whatever reason, never became superstars, but whose music you think is underrated, or perhaps, just undiscovered and unknown? Somebody who didn’t get the credit that they should have.

Larry McDonald: Joe Higgs.

Q: Whenever I read about him, in books that are written about reggae, [he] is certainly given credit as the “Godfather of Reggae,” having weaned Bob Marley and so many different [artists and bands].

Larry McDonald: But like, Joe had his issues with [the song] “Steppin’ Razor,” you know? Joe had to take Peter [Tosh] to court over that song; Joe wrote that.

Q: Wow. I didn’t know that.

Larry McDonald: Yeah.

Q: Did he win?

Larry McDonald: Yeah. It’s like Joe never got the acclaim that he should have. Forget the whole Wailers stuff. Joe was a [legendary] artist in his own right.

Q: Now I thought back in the day in Jamaica, before Bob Marley, didn’t [Joe Higgs] sing with, I can’t remember –

Larry McDonald: Higgs and [insert] Wilson! Oh my, they were one of the first motherfuc*in’ monster hits!

Q: So didn’t [Joe Higgs] get respect through that?

Larry McDonald: Yeah, everybody knew that, but Joe was just a force. Actually, I want to do a tribute album to Joe Higgs.

Q: That would be awesome. Now, as I tipped you off [to] a few days ago, I consulted your old friend Amy Wachtel [also known as the the “Night Nurse”], who, like [your friend] Nan Lewis, has been a fixture in the reggae community for decades, to ask her if there were any particular questions I should ask you tonight; she had a few excellent suggestions.

Larry McDonald: Oh no, I’m really scared. (Laughing.)

Q: One of her questions is, what are some of the differences between when you toured when you were in your 30s and such, as compared to now that you’re in your 80s?

Larry McDonald: The difference is, in my 30s, I was still making my way into the whole game. And I’m not bitter. But I’m very cognizant of the fact that, you know, conga players – I always say this: You never hear anybody say, “Look, I’m gonna put a band together. I’m gonna get this kick-ass conga player and put a band together.”

Q: Last time [I interviewed you], you said “they’re the first ones to be fired, last to get paid – ”

Larry McDonald: Oh, and get the least money. All that sh*t, man. I went through all of that. But this is what I fuc*ing wanted to play. This is what I’m about (pointing to a set of congas); this is what I wanted to play. And I’m happy I made a living out of it. [Even if] I didn’t make any money “really.” But to go back to what Amy wanted to know: now, when I’m coming to do [a] gig, I tell’em what kind of equipment I want, and it’s there. I don’t have to convince anyone. But the amount of time I spent to get to that point. Being ignored. Being patronized.

Q: So now you feel like you’re finally starting to get the respect you’re due?

Larry McDonald: You know, Steve, I never lost that resentment that I had. Because it kept me – it kept me focused. I had to show motherfuc*ers.

Q: It drove you?

Larry McDonald: Yeah. It fired me up. But, okay, I’m glad now that Jamaicans are paying attention to percussionists. [Like, for example, ] [t]he conga player for Chronixx, Hector [Lewis].

Q: Larry, maybe it’s a silly question, but in 2014 you were on the “Jake Feinberg Show” and you said that in the ‘80s all the famous reggae stars would always travel with a cook. I was curious if you’re aware if anyone still has a cook as part of their team [or “entourage”] when they’re traveling?

Larry McDonald: Some people do, but it’s not like a must-have like it used to be.

Q: In all your years of touring is there some reggae artist who stands out as being a great cook?

Larry McDonald: I burn a mean pot.

Q: (Laughing) What do you cook when you cook?

Larry McDonald: Whatever I feel like.

Q: How do you cook on the road though?

Larry McDonald: No, I gave that up. When I [played for] Taj Mahal, we used to carry the whole works. The Coleman stoves, the this, the that. And I went straight vegetarian, and I forgot where I was. And I couldn’t find anything to eat. The only thing I could get was steak, and I had weaned myself off of steak. [And] I don’t eat fish unless it’s cooked by a Jamaican or West Indian. It’s just a thing with me. (Laughing.)

Q: Is there any difference between the crowds that come to reggae shows nowadays as opposed to when you were in your 30s?

Larry McDonald: The crowds back then were better dressed. Better put together. Bands then were [also] better dressed. It was a thing.

Q: The last time we spoke, you spoke about the influence the drummer “Big Black” had on you. Has your percussion style changed or morphed over the years since you learned from Big Black?

Larry McDonald: What I got from Black was more a way to think about it. And what I ended up doing was finding a way to play that I could mold to the circumstance that I was in, and still sound authentic. Not sound like I was just super-imposed on whatever it was. So, my style of playing is very personal. But I’ll take it and adapt it to whatever the circumstance is. Because I think I should be able to do that. I just think I should be. If you can conceive of that sh*t – conceive of my [percussion] in that – I’m gonna give it a try. [But] [t]he whole way that I see what I do in relation to the music has evolved over the years. Because there wasn’t any template to follow. There were very few conga players. But then there wasn’t any reggae [back then]. Or any ska. (Laughing.) So when that came along, I put my version that I play on congas of the indigenous beats, and putting that into the music. And I got some resistance because it wasn’t Rasta drums. Or Burru drums. It was kind of an outlier, I think. See I had to think about who was before me in terms of playing congas. Not in terms of indigenous drumming. [Because] that was the instrument that I wanted to play. Only two people I could think of really was Noel Seale and Jerome Walters. They were before me. So, here I am, using this instrument that’s not all that much used in reggae music.

Q: The congas?

Larry McDonald: Yeah. So here I am trying to make a go of it and play what I need to play on congas, but I had to play well enough so that they used to ask me what I was playing. As opposed to the sound it was making. Because the tonal difference between the Rasta drums and the congas is pretty vast. So, I’m doing all I can to fit in right across the board. Musically, the first thing I learned was, stay out of everybody’s way. That’s the first [lesson] I [learned]. Find some place [in the music] where you can play. That’s what everybody does, you know? They get the tune. And the guitar player’s playing here, the drum and bass [player] are playing here, the keyboard player’s playing here – you’ve got to find some place [within the music] to play.

Q: I’m not a musician, but I think you’re describing what music sounds like at its best: When each part of the band is contributing at the right moment in a tune, to make the music better.

Larry McDonald: That’s what should happen every time a group of guys goes [up] on the bandstand [together]. That’s what you should be aiming for. To just be in service to the music.

Q: Maybe it’s not the only reason, but do you think that the music goes off [of the rails] when one person in the band is trying too hard – doing too much to let their instrument shine. Is that what you were sort of [getting at] when you’re saying “stay out of everybody’s way”? [That] [i]f your instrument is overshadowing someone else’s instrument, that you’re not doing it right?

Larry McDonald: It’s not – I’m not focused on trying to be on top of anyone musically. What I’m trying to do is find where the whole pulse of the rhythm section is. And [I’m] just trying to stay in there and do stuff that fattens that feeling.

Q: Did you say “fattens that feeling”?

Larry McDonald: Fattens, yeah!

Q: “Fattens.” I like that. That’s awesome!

Larry McDonald: Yeah, fatten it up! I try pretty much to play everything out of Jamaican indigenous rhythms. I draw pieces from that. I’ll take a pattern from this –

Q: When you say Jamaican indigenous rhythms, do you mean the Arawak Indians?

Larry McDonald: Kumina, Burru, Mento, Pocomania. All the stuff that was before. The stuff that came on from slavery, all that stuff that remains. I was disposed to it because for a time I was with the National Dance Theatre Company in Jamaica. And you had to learn somewhat about [all] that kind of stuff. Because you’d be playing that, you know? So, my playing, at some point during any song, if you listen to me, there’ll be something that’s totally Jamaican. It’ll just pop up because it pops up in my head. (Laughing) It’ll just jump out.

Q: [And] you found a way to make that work throughout your career, so that’s cool.

Larry McDonald: This is what I’m saying. It’s so hard to talk about the style because I try to put all the stuff that I’ve learned – I try to put it in a place where I can access all of it, at a moment’s notice, if I’m faced with any kind of unusual musical situation. I have to have something to play. I have to find something to play. And then, when I find that, that trail leads me down this road, and I hear something and go here, and then by the time I get to the end of the tune, you’ll think I wrote the sh*t. (Laughing.)

Q: Cool. Last two questions for you, Larry. The first one is about weed, and again, it comes from Amy Wachtel. She wanted to know if you thought the herb nowadays is different? Specifically, she asks, “is it too strong” [nowadays] compared to what I would call the “sad old days,” when there wasn’t as much variety?

Larry McDonald: You can still get the kind of herb that makes you comfortable. But, I don’t know man, sometimes I like to get my butt kicked, you know? (Laughing.)

Q: (Laughing). Now every time I see you perform Larry, you’re basically smoking a spliff, one after another onstage. Has there [ever] been a time when you haven’t smoked weed while playing drums onstage?

Larry McDonald: Yes, back in the [truly] bad old days when you couldn’t smoke weed [onstage].Q: Now this may be obvious, but for people who are not musicians, can you speak for a moment [about] your observations of the importance of marijuana to the creativity and the performance of reggae music?

Larry McDonald: Speaking for myself, the first time I smoked, I was listening to a record and, I don’t know what it was, but I heard the trumpet player take a breath. That’s the first time I heard that sh*t on a record, man! (Laughing.) And I was torn up.

Q: So [when smoking marijuana] you can hear things in the music you might not otherwise hear?

Larry McDonald: Yeah, for me. I’m not saying for anybody else.

Q: Last question, Larry. And I [also] asked [Lee] Scratch [Perry] the same thing [tonight] too: Do you have any thoughts about Kanye West and his love for Donald Trump?

Larry McDonald: I think the gentleman needs to be informed about sh*t before he speaks. I don’t know where he gets his information from. I’m not a fan of his sh*t. If you find yourself in the position of the kind of influence that these people can command, [and] you want to say something, learn something [first]. Don’t just come with some stream of consciousness. If you don’t know about something, don’t say something because you’re just pissed off and think you’ve got to say something. Don’t do that. If you want to get on a soap box, figure out what you want to say. Study something about it, you know, make sure you’ve got your facts right. And then say something. You don’t just get up and start blathering. I don’t like that, man.

Q: Larry, it’s always great to talk to you; you have dropped so much knowledge during the two times we’ve [spoken]. Whenever you come through Los Angeles and want to talk some more, please just let me know.

Larry McDonald: Thank you.

•••• •••• ••••• •••• ••••

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Photos by Stephen Cooper

Some videos featuring Larry McDonald

Sub Atomic Energy Lee Perry & the Upsetters – Blackboard Jungle

Joe Higgs — Interview with Reggae Beat

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq