Lee Scratch Perry: “Higher Than Moses”

Editor’s Note: Click on images to view them without adverts.

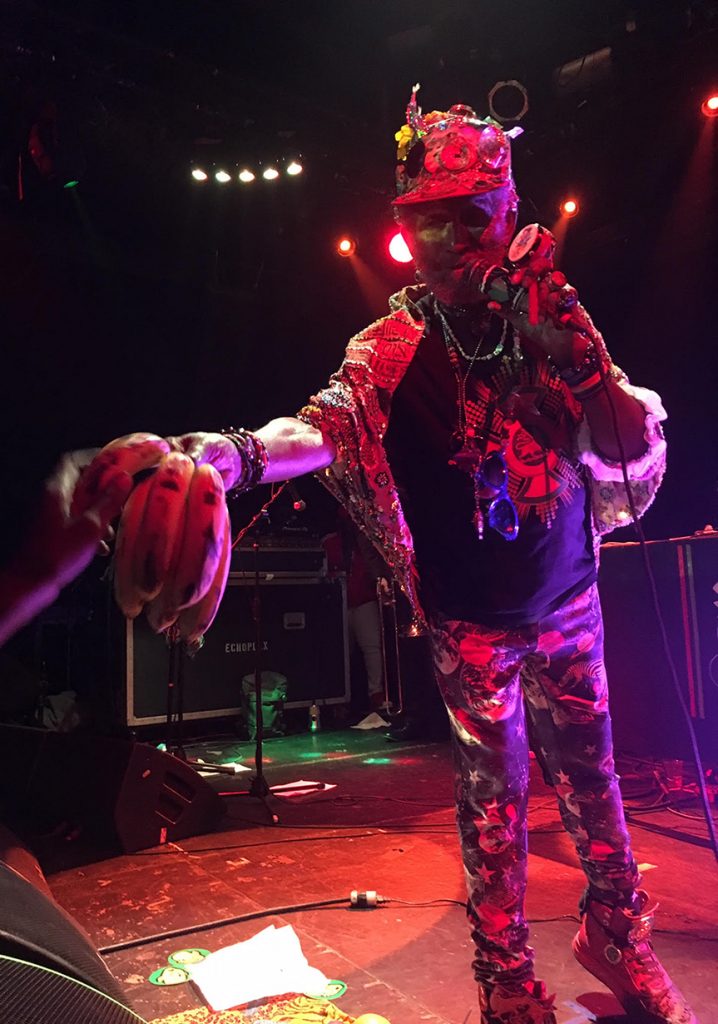

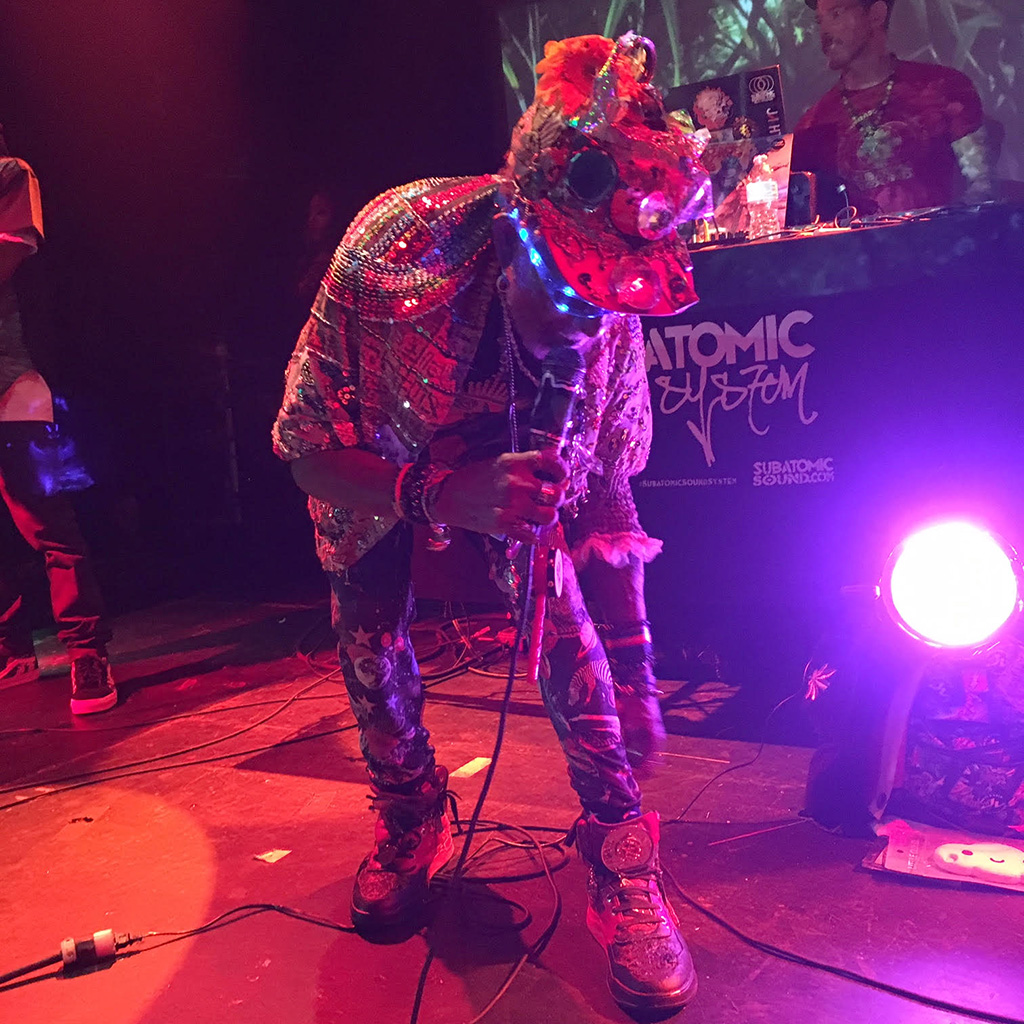

My reggae sixth sense told me it’d be a good idea to buy an extra Rasta-colored ring on the off-chance legendary Jamaican music producer Lee “Scratch” Perry might return to Los Angeles; ever since meeting “The Upsetter” last November, I’d been itching to continue our conversation. So I was thrilled when I learned Perry’d be in town again — this time to celebrate the 45th Anniversary of his “Blackboard Jungle Dub,” the first dub album ever – and even more ecstatic when Perry, who was in a gregarious and expansive mood, smiled warmly at me and immediately put on the beaded ring I sheepishly handed him, just like when I interviewed him last year.

While Perry’s once-in-a-generation creativity and influence is indisputable, too often the focus, especially in recent years, has been on Scratch’s eccentricities – his onstage antics, his flamboyant attire, or, the impenetrable sing-song parables he, at times, speaks in. But, as Larry McDonald, a legendary percussionist in his own right, who knows Perry better than mostly everyone, explained: “I think he’s eccentric. I don’t think he’s crazy … Because he makes a lot of sense. And a lot of [what] he says goes over people’s heads. Plus, the heavy Jamaican accent …. Forget the thick Jamaican accent. If you listen to him, you’ll understand what he says.”

Having talked to Scratch twice now, it’s obvious Larry “Mac” nailed it; if you listen to Scratch closely, he does make a lot of sense. And, I’d add, when you can’t understand him, when what he says does go over your head, his rascally smile and the knowing impish glint in his eyes reveal, just as one might expect from a masterful producer of Perry’s stature, that that’s exactly how he planned it.

What follows, for your review, is a transcription of my second epic interview of Perry, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Scratch, that was a great show! It’s great to see you again; it’s almost been a full year since I saw you here a year ago. How have you been doing? How has your year been?

Scratch: I’m doing myself over. I’m making over myself.

Q: What’s been the best part of the year for you?

Scratch: The best part? Look, I need a spliff. Who have any? Make me a spliff. Larry! [Yelling to percussionist Larry McDonald, who responds, “Yes.”] You can get a spliff –

Q: Look, Scratch, I [brought] one for you – here. (Handing Scratch a pre-roll, Scratch takes the spliff, lights it, inhales deeply, and blows a large cloud of smoke.) So, what was the best part of the year for you?

Scratch: The best part? Everything [was]. Our father who art in heaven, [will] always be [in] God’s name.

Q: That’s true. Now when we met last, you said, quote: “When the time come for Bob [Marley] to recognize the truth, Bob turn him back on the truth . . . . When Bob did not choose God, he chose the devil.” I was surprised when you said that. And I asked you: “Bob didn’t choose God? He chose the devil?” And you said: “That’s why him not here.” Can you explain what you meant by Bob choosing the devil, and that being the reason why he’s not here?

Scratch: Well, Bob choose cigarettes and choose cocaine. Bob choose cigarettes and cocaine.

Q: Is that how he got sick? Is that how he got cancer?

Scratch: What you give, you get. What you send out, it comes back to you. What do you use? You can’t use God. If you believe in God, God will make everything possible. Through God, there is nothing impossible.

Q: True.

Scratch: With God, everything is possible.

Q: Respect.

Scratch: And if you believe in God, God kills death. But God [also] needs death.

Q: True. Aston “Family Man” Barrett [bass player in both the Upsetters and the Wailers] has –

Scratch: I hear that he’s paralyzed now?

Q: I don’t know. Is that true?

Scratch: That’s what mi hear, that he’s in a wheelchair.

Q: He said [in an interview excerpt on p. 402 of Lloyd Bradley’s book “Bass Culture: When Reggae Was King” (Penguin Books 2000)] one reason why you and Bob [Marley] shared a [musical and spiritual] bond was because you were both country boys initially, before you came to Kingston –

Scratch: Me and Bob are country boys, yeah.

Q: Do you think that’s why you and Bob had such a [strong] bond, because you both came from the country?

Scratch: Yeah. (Nodding head.)

Q: What is it about growing up in the country that makes you a better musician, or better able to appreciate the music?

Scratch: I grew up with the secret life of the plants. I grew up with the trees, the flowers, the roses. I grew up and get higher than Moses. I’m a Maroon. If I wasn’t a Maroon, I wouldn’t do what I do to [late Jamaican musician and producer] Byron Lee. Byron Lee’s a Chinese. He eat dog, and me no eat dog. Mi no eat cat. Mi no eat meat. Mi no eat no chicken. And mi no eat no chicken back.

Q: [You’re] [v]egetarian?

Scratch: Yes.

Q: Now before you began in music full-time, you used to drive a bulldozer, moving boulders in Negril. That was a job you liked, right?

Scratch: Yeah.

Q: In addition to the bulldozers, you also drove [regular] tractors I think, too. Because you have a song [about] how you used to drive a tractor in Negril –

Scratch: In Negril.

Q: So you drove both?

Scratch: Yeah.

Q: Did driving those big machines, the bulldozers and tractors – with the power that you had under your control, and the sounds that they made – did that play a part in your appreciation of and [later] mastery of the mixing board?

Scratch: Exactly as you say it. Absolutely.

Q: In 2001, you visited Roger Steffens’s “Reggae Archives,” about five-minutes from [the Dub Club]. And [there] you said that you wrote the song “Small Axe” all by yourself, without Bob Marley. You said [in an interview excerpt on p. 121 of Steffens’s book “So Much Things to Say: The Oral History of Bob Marley” (Norton 2017)]: “I Upsetter write this song. I am the Small Axe. Bob was not even there when I wrote this song.” Do you remember that? Saying that?

Scratch: I am the Small Axe, so why you want to bigger. I don’t want to contend with no bigger. Because if I get bigger, mi couldn’t identify myself anymore. If mi get big and fat, mi couldn’t identify myself anymore. Mi no want no bigger business. And that’s why I stay likkle Scratch. Likkle sh*t. Mi name’s Scratch, sh*t. Sh*t is a must. Did you know that? Sh*t is a must.

Q: Sh*t is a must, that’s for sure.

Scratch: Piss. Did you know that piss is a must?

Q: All those are a must.

Scratch: Poop is a must. (Laughing.)

Q: Poop is a must. (Laughing.)

Scratch: Fart is a must. (Laughing.) Sleep is a must.

Q: But did Small Axe – is Small Axe your song? Is that your song and no one else’s?

Scratch: It’s a battle axe, it’s not [a] small axe alone.

Q: There’s a fan of yours whose name is “Blaze.” He lives in Kampala, Uganda –

Scratch: Who?

Q: There’s a guy named “Blaze,” and he’s a fan of yours. He lives in Kampala, Uganda. And he wants to know: Is it true that “Small Axe” was recorded as a message of defiance to the big three recording labels in Jamaica — at that time it was Coxson [Dodd]’s “Studio One,” Duke Reid’s “Treasure Isle,” and [Ken Khouri’s] “Federal”?

Scratch: Who tell you that? How [did] you know?

Q: Uh, people speculate. People have said that over the years. And so [Blaze] wants to know, how true is that? Is that true?

Scratch: One hundred percent. One hundred percent.

Q: At Bob Marley’s funeral, [former Jamaican prime minister] Edward Seaga said Bob “was the embodiment of discipline and he personified hard work and determination to reach his goals.” Do you agree with that?

Scratch: [Bob] was very intelligent. If you give him [a] [lyric], he’ll never forget it.

Q: Bob would? If you gave him a [lyric] –

Scratch: If you give him a [lyric], he’ll never forget it. He just do exactly like you give it to him. And him can add to it.

Q: And make it even better?

Scratch: (Nodding head.)

Q: Amy Wachtel, known as the “Night Nurse,” a fixture in the reggae community for many years, wants to know if you’re interested in collaborating with some of the new conscious artists such as Chronixx, Protoje, and Hempress Sativa?

Scratch: I’m okay with Chronixx. But mi no like the word [chronic]. Because the word [chronic] is a pain. Mi no say mi dislike him. But the word chronic mean pain.

Q: Constant pain. Who do you check musically outside of reggae, in terms of other genres. Whose music do you really appreciate outside of reggae?

Scratch: Hip hop.

Q: Any artist in particular?

Scratch: It doesn’t have to be [any] special artist. Hip hop is good. It’s fun. It can do lots of things.

Q: Amy Wachtel, who I believe knows you, says there’s a tortoise named “Aristortle the Greek” in New York City. And she wants to know whether you would come to New York City to meet her tortoise?

Scratch: Yeah.

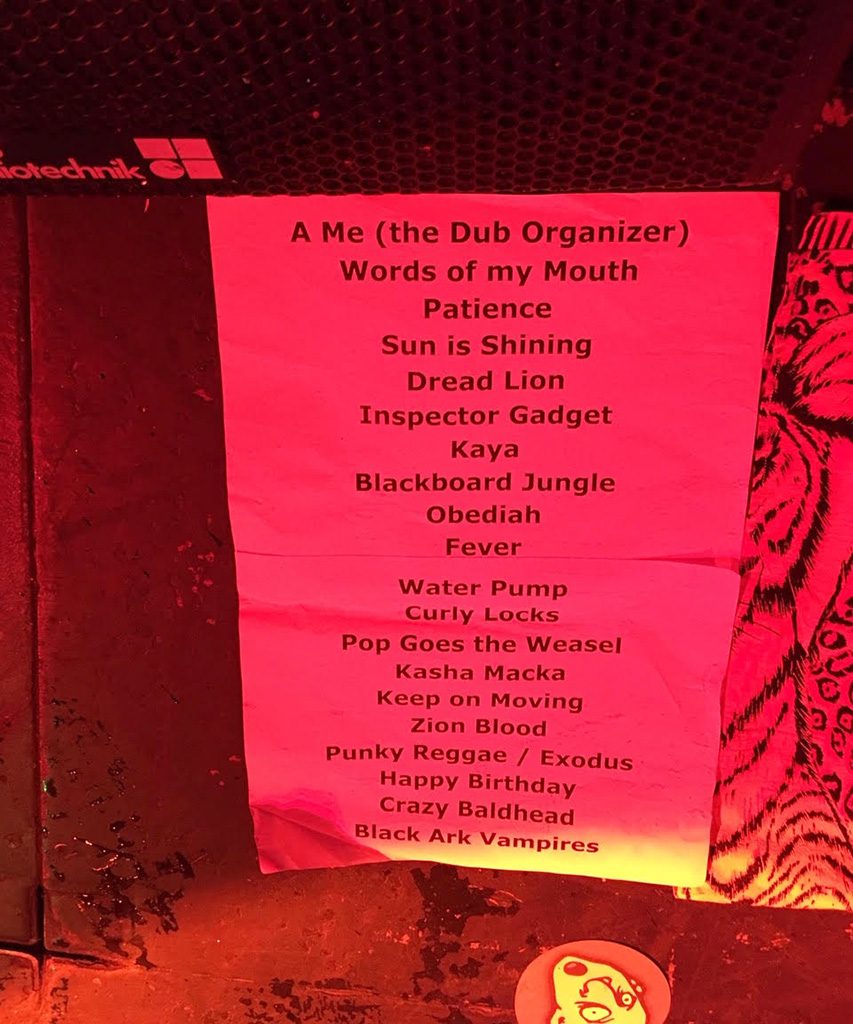

Q: Okay. That’s what she wanted to know. Now, you played some music tonight from [your 2017] album “Super Ape Returns to Conquer” [which ruled the electronic and reggae charts in 2018, as well as some of your other famous classics]. [But tonight] was [primarily] about celebrating the 45th Anniversary of your [famous] “Blackboard Jungle Dub.”

And last time when we spoke, you said dub music is “underground music.” That it contains “underground truths.” Now you built your famous Black Ark studio not long after parting ways with Bob and the [rest of the] Wailers. And it was there that you recorded the Blackboard Jungle Dub. Was one of the reasons why you created dub music because you had disputes with singers [over money] and you wanted to just not have to deal with them [anymore]?

Scratch: No, there was too much copy[cat] artists at that time. They hear you do something, and they want to copy what you do. [They have] no thoughts [of their own].

Q: So you wanted to make something so original they couldn’t copy it?

Scratch: Yeah. [I] want[ed] to do something different. And there were too [many] reggae artists. I wanted to mash it up and change that, [to] create things, [and] then destroy them.

Q: And you definitely did that. Kanye West is a very popular artist and he’s sampled your music before.

Scratch: What can I say about him?

Q: What do you think about Kanye West?

Scratch: He’s not even an idiot.

Q: He’s dumber than an idiot?

Scratch: (Smiling and nodding.) He’s a true fallen angel. He’s not even a cockroach.

(Everyone laughing.)

writer Stephen Cooper

Q: Last question: There’s a [late emeritus] professor of religion in the United States [named Leonard E. Barrett, Sr.] – he [was] at Temple University. He wrote a book called “The Rastafarians” [Beacon Press 1997]. And [in it] he [wrote, at page 119,] that the Rastafarians believe whites are destined to destroy themselves with nuclear weapons, after which, only the black race will survive on the planet.

Scratch: (Laughing deeply.)

Q: Is this something you think is true?

Scratch: Well, listen. You have a shadow?

Q: Yeah.

Scratch: What do you expect your shadow to look like? What color do you think your shadow’s supposed to have?

Q: Black. Everybody’s shadow is black, is that what you’re saying?

Scratch: (Nodding. Smiling.)

Q: That makes sense to me. Mr. Perry, thank you so much. This was a great interview.

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Photos by Stephen Cooper

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq