Tony Chin is unstoppable

Tony Chin’s Unstoppable, Historic Career in Music (The Interview: Part 1)

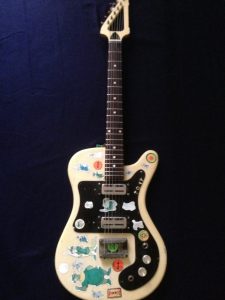

On his forthcoming solo album, “Unstoppable,” Tony Chin – one of the greatest rhythm guitar players ever and a founding member of “Soul Syndicate,” the top studio band in Jamaica during the 1970s – sings in his unique, mellifluous falsetto: “If you look in my eyes then you can see some of my deepest memories of the country where I came from; Kingston, Jamaica, is the city where I was born.”

(Stephen A. Cooper)

After being introduced to Tony Chin by my friend, legendary sound engineer Scientist – and after spending time in the recording studio together – I made arrangements to interview Tony at the Golden Sails hotel in Long Beach, California (where he plays each Sunday as part of legendary bassist George “Fully” Fullwood’s band). I wanted to better “look in [Tony’s] eyes,” to “see [and hear directly from him about] some of [his] deepest memories” – not only about Jamaica, but about his historic half-century as a professional musician.

So on June 30 and July 7, before he performed at the Golden Sails, Tony and I spoke for several hours about numerous subjects of interest to Jamaican music historians and reggae lovers alike. Because the interview is full of fascinating anecdotes and precious insight that, for posterity’s sake, cannot be excised, I’ll be releasing the transcript in parts, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations. This is Part I. Enjoy!

Q: Greetings, Tony. It is truly an honor to be able to interview you here at the Golden Sails hotel.

Tony Chin: Yeah man. Give thanks!

Q: Tony, I want to begin by reading a quote from reggae historian Roger Steffens: “Tony Chin is one of the greatest unsung heroes of Jamaica’s golden age of reggae[.] As the rhythm guitarist for the Soul Syndicate, the prime studio band in Kingston during that electrifying decade, Tony helped anchor some of the biggest hits of the era.” Now because I believe your professional recording career began in the late 60s, is it accurate to say you’ve been in the music business – as a professional musician – for close to 50 years?

Tony Chin: Yeah, that’s true.

Q: Now even though you are primarily associated and thought of as being the rhythm guitarist for the Soul Syndicate, which started off being called the “Riddim Raiders,” you’ve worked as a freelance guitarist or session musician for virtually all of the most famous reggae producers in the 1960s and 70s. The list is too long to [recite all of their names], but correct me if I’m wrong: During your career you’ve played your guitar on works for Bunny Lee, Lee Scratch Perry, Niney the Observer, Duke Reid, Coxsone Dodd, and Joe Gibbs. True?

Tony Chin: We never really worked for Coxsone Dodd. But all those others, yes, and more.

Q: Now it’s not really fair to ask but, out of all of those producers, if you had to [choose], which one would you say would be your favorite to work for? And why?

Tony Chin: Bunny Lee is one of them. Because he’s one of the first producers that really [took Soul Syndicate] in the recording studio, and break us. Bunny Lee, we call him “Striker Lee,” you know what I mean? And then, we have Niney the Observer. He was one of the next ones that really project us. And was honest with us. [But] Bunny Lee, [Soul Syndicate] did a lot of recording with him. And if it wasn’t for Bunny Lee, we wouldn’t have been doing a lot of recording – possibly. Because I remember we were doing a session with Bunny Lee, and this producer named Phil Pratt came in the studio. And he said, “Tony, Fully, Santa, I’d like to come record some songs at Randy’s next week,” or whatever. And this producer Phil Pratt, we worked on a tune with him, one of the first recordings we [did] with Dennis Brown, called “What About the Half?” And we did [another] tune for him and Gregory Isaacs: (singing) “All I Have Is Love.” But as I say, Bunny Lee is the man. And Niney. He was one of [Soul Syndicate’s] favorite producers.

Q: Those were two of your favorite producers?

Tony Chin: Yeah man. Every song at that time [in the 70s], although Niney didn’t call the band the “Soul Syndicate” – he called us “the Observers” – we are the ones [who played for him].

Q: I think that you’ve said before that producers all had their [own individualized and possessive] names for their studio bands.

(Stephen A. Cooper)

Tony Chin: Right.

Q: So as a result you’ve played for all of these different bands: The Aggrovators, “Randy’s All Stars,” [Lee Scratch Perry’s “Upsetters,” Jack Ruby’s “Black Disciples,”] all of these studio bands –

Tony Chin: Alright, the Aggravators, [was] Bunny Lee’s studio band. It’s a “studio band” because sometimes it’s not all of Soul Syndicate [playing] together on [a] record. Sometimes it’s [lead guitarist] [Earl] Chinna [Smith] and [drummer] Santa [Davis]. I am not there. [Bassist] Fully [Fullwood] is not there, [and so] maybe it’s Robbie [Shakespeare] playing bass.

Q: Different [musicians] were [circling] in and out?

Tony Chin: Yeah, different [musicians] [were] coming in [and out]. But [Niney’s] the Observers was strictly [Soul] Syndicate with some horn players.

Q: Especially all those Dennis Brown [hits]?

Tony Chin: Ah yeah, that’s Syndicate. [And] [s]ome of Randy’s All-Stars was all Syndicate, [too], but not all of them. [Also] Syndicate did an album for Joe Gibbs (showing me vinyl records) “African Dub, Chapter One,” and “African Dub, Chapter Two.” You see?

Q: You know I asked [legendary sound engineer] Scientist to tell me what are his favorite dub albums, and he said African Dub was one of them.

Tony Chin: This is one of the best dub albums, man. African Dub, Chapter One, and African Dub, Chapter Two; I mean, it’s amazing.

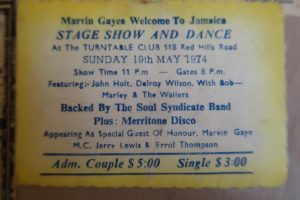

Q: Just to showcase the amazing breadth of your career as a guitarist, and also to show why we can’t possibly cover all of the important music questions I have for you in [only] one [interview], and why we’ll need to meet up again, I want to list a few of the stars you’ve played with. Correct me if I’m wrong but you’ve played and recorded music with: Bob Marley and the Wailers, Dennis Brown, Burning Spear, Big Youth, Johnny Clarke, Ken Boothe, Gregory Isaacs, The Mighty Diamonds, U-Roy, Jimmy Cliff, Freddie McGregor, Judy Mowatt, John Holt, Horace Andy, and Max Romeo.

Tony Chin: Yeah man (laughing). All dem and a lot, lot more.

Q: Before we dig deeper into the music, I want to take a step back for a moment to ask you a few biographical questions, questions about your background, family, and coming of age.

Tony Chin: I was born in Greenwich Farm, Kingston, Jamaica.

Q: I understand you were born at the public hospital?

Tony Chin: Yeah.

Q: And I read that your father [Alvin Chin] was part Chinese and –

Tony Chin: – and part black, yeah.

Q: Your mom[, Inez Noyan,] was part Indian and part black?

Tony Chin: Yes.

Q: And did both your mom and dad raise you?

Tony Chin: First, when I was growing up in Greenwich Farm, yeah, they raised me till I was about 9 years old. And then [my mom and dad broke up, and my mom and I] moved to Trenchtown. And I grew up [then] in Trenchtown. I think we [left] Trenchtown when I was about maybe 14. And [then my mom and dad got back together and] we moved to a place called Tavares Crescent close to Trenchtown. And I lived there for a few years until about 17 [when my mom migrated to America]. And then [my dad and I] moved to 179 ½ Spanish Town Road. And that’s where it all started. That’s where my music career started. My father came home with a guitar [he bought] from a drunken man. I was not playing in a band yet or anything. My friend Maurice Gregory was a singer, but he could play guitar. [George] “Fully” [Fullwood], Fully used to come up – we used to sing on the street corner in a group. Singing Beatles songs, singing rocksteady music and ‘tings. Like The Paragons. The Melodians. We’d be singing those things.

Q: Greenwich Farm is like a garrison? A ghetto? A tough spot?

Tony Chin: Yeah. Greenwich Farm and Trenchtown, yeah, they are ghettos. Spanish Town Road is close to Greenwich Farm. So we were singing on street corners, and Maurice Gregory used to play the guitar. And Fully would sometimes play guitar. And we was singing. And this guy used to walk past and he’d see us play; he was a shoemaker. And one day he came to a friend of mine, a friend of mine named Benji, to give me a message. And he said that he had some guitars and a drum set. And he wanted to put a band together, if I’m interested.

Q: Wow.

(Stephen A. Cooper)

Tony Chin: At that time Fully used to play guitar. And I took him down to Fully’s house. And this guy named Benji had some equipment, an amplifier and stuff from the music store that he’s paying monthly for. And Fully’s father pay it off.

Q: Was that the first investment in the Soul Syndicate?

Tony Chin: It wasn’t the Soul Syndicate [yet], it was the “Riddim Raiders” [back then]. So when Fully started playing bass, he was playing bass on a guitar not a bass. [We] had two guitars. And that’s how it all started. Then we had this guy Cleon Douglas came in as our singer. And I showed him a few [guitar] chords. And he started to play rhythm guitar, too. Chinna wasn’t even in the band yet. Then Fully’s brother changed the name of the band to “Soul Syndicate.” Then we had this keyboard player who came and played with us, Tyrone Downie. This was before Bob [Marley].

Q: Didn’t he play for Bob [Marley]?

Tony Chin: Yes! He was Bob Marley’s keyboard player. He came and played with us way before Bob. Then you have Wire.

Q: Wire Lindo?

Tony Chin: Yes, that was before Bob[, too]. Then you have Glenn Adams, [another] keyboard player. He used to play on all those backing songs for the Upsetters. And he was part of “The Hippie Boys” with Reggie, Family Man, and Carly. Those people used to play with us. Glenn Adams made [Soul Syndicate’s] uniforms.

Q: And [they both] played in Soul Syndicate!?

Tony Chin: Yeah!

Q: What did your dad do for a living?

Tony Chin: He was a fisherman. And then he was a shoemaker. And then he was working for a drink factory – that makes soft drinks.

Q: Was your mom working, too?

Tony Chin: My mom migrated to America. She was living here. [But before that] [m]y mom was a domestic servant; in America, you call it a “maid.” Cleaning the house and washing clothes. ‘Cause I remember when I was a kid, maybe 6, I used to go with her to work because they didn’t have no babysitter to babysit me. So she took me with her to work.

Q: Did she work in the hotels? In the resorts?

Tony Chin: No, not in hotels. In people’s houses. Rich people’s big houses. She’d go up there and wash clothes, clean the house, and cook for them.

Q: So after your parents broke up, then she moved to the United States?

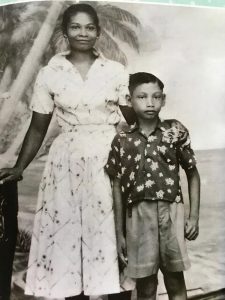

(Tony Chin)

Tony Chin: She moved to America, yeah.

Q: Were you able to stay in touch with her?

Tony Chin: Yeah, yeah, because every once or twice a year she would come and visit me on Spanish Town Road.

Q: Were either your father or mother musicians?

Tony Chin: Neither of them.

Q: Did your parents encourage your passion for music?

Tony Chin: My ambition when I was a kid going to school, before the music thing for me, I wanted to be a pilot. I wanted to fly planes. That’s what I wanted to do. I was in the Boy Scouts. And then when I was in high school, I joined the cadets. I loved militant type of stuff.

Q: By the way, you’re still wearing a militant uniform (Laughing).

Tony Chin: (Laughing) Yeah, you see. I love the military business [so] I joined the cadets. And at first I was playing bugle. But it hurt my jaw, and I didn’t like it. So I switched to playing side drums.

Q: This was all in the cadets? They had a cadet band?

Tony Chin: Yeah man, they had a military band. I really loved that. You wear short-pants and things. And I noticed you had a thing called “Girl Guides.” Like Girl Scouts. And the Girl Guides, dem always looking out for the cadets. (Laughing)

Q: Now Tony there are many Jamaican citizens that, like you, have Chinese ancestry. And indeed the surname “Chin” is not uncommon in Jamaica.

Tony Chin: A lot of Chins!

Q: It’s not even an uncommon [last name] in the reggae music industry. Are you related by chance to Chris and Randy Chin of VP Records?

Tony Chin: No.

Q: Just this month an article came out in issue number 24 of Topic Magazine with the title: “Redemption Songs: Chinese American music producers helped turn reggae into a global sensation.” It’s actually done as a comic strip or animation. And it says, in part, that in 1967 Shanghai Singer Stephen Cheng traveled to Jamaica and collaborated with [music] producer Byron Lee, who was also Jamaican-Chinese. This article by Krish Raghav says, “Cheng chose to sing an old Taiwanese folksong and Lee provided the backbeat.” I was curious about this and wondered if you knew this Stephen Cheng, were familiar with this story, and if you know whether it’s true?

Tony Chin: No I’m not familiar with the story, but overall Chinese [people] have a lot to do with Jamaican music. Channel One [was] Chinese-owned.

Q: Yeah, the Hoo Kim brothers?

(Tony Chin)

Tony Chin: Right, the Hoo Kim brothers. That’s Channel One [Studio]. Because listen, I know those brothers from way before they [opened up] Channel One [Studio]. They used to own a bike shop where I lived on Spanish Town Road. Right at the corner of Maxwell Avenue and Spanish Town Road. It was before they were in music. And then they built the studio, Channel One. And when they built that studio, and the studio was new, they called us, the Soul Syndicate, to come in and test the equipment.

Q: Wow!

Tony Chin: We were the band that tested the equipment to make sure it was working.

Q: Soul Syndicate tested the equipment out for Channel One!?

Tony Chin: Yeah man, a lot of [things like] that [are] not [recorded] in the history [of Jamaican music]. One of the first hit songs that came from Channel One was Gregory Isaacs song, “All I Have Is Love.” Many, many hit songs [were] recorded in that studio. [But] listen, the Chinese dem, remember Beverley’s [record shop and recording studio]? You had a Chinese guy that owned Beverley’s, and [Beverley’s] recorded Bob Marley’s first song.

Q: Despite the fact that so many Jamaicans with Chinese ancestry have been involved in the music business in Jamaica, did you ever at any time feel as if you were being discriminated against or otherwise treated unfairly by anyone in the industry – either by artists or by producers – because of your Chinese ancestry?

Tony Chin: No, no, no. I didn’t feel discrimination. Because we were all from the ghetto.

Q: Now I want to spend a few minutes asking you about your work and relationship with the undisputed king of reggae music, Bob Marley. In 2018, you were interviewed on the Jake Feinberg radio show. And on that program you said the first time you met Bob Marley was [the day] you recorded [the famous song] “Sun is Shining” [with him]. This is one of my personal favorite songs of all time.

Tony Chin: (Laughing) Alright!

Q: And you told Jake Feinberg that you and Bob got into a big fight in the studio [that day]; Bob got angry with you, you said, because you couldn’t play the chords the way he wanted you to. And you got defensive. Then you said Peter Tosh “peaced out” the dispute, the song was recorded, and it became a giant hit. Can you say more about what happened?

Tony Chin: Yeah, we got in an argument because I couldn’t play the guitar like [Bob] wanted [me to] with my little finger. I couldn’t understand the style.

Q: And Bob was trying to show you [the style he wanted] with his guitar?

Tony Chin: Yeah, and I didn’t understand him. And Bob [was] a perfectionist. And he got irritated with me. And he said, what am I doing there if I can’t play the guitar. But he didn’t say it like that. He said: “Bwoy, what the blood clot!? You can’t play the guitar!?”

Q: (Laughing) This was in just the first few minutes of you being there in the room with him?

Tony Chin: (Laughing) Yeah. This was the first time I’m meeting him.

Q: So what did you say?

Tony Chin: I said, “Bob, you bumbaclot, mi no play the guitar [for] you.” And Peter [Tosh] Fully, and Bunny [Wailer] and dem kinda watchin’. And dem just cool down the argument.

Q: Did they tell Bob to give you a chance?

Tony Chin: I don’t remember exactly, but they said [something] like: “Gentlemen, this is reggae music we a-play. [It’s] One love. One vibe.

Q: After you and Bob fussed and [fought] how many more takes did it take before the song was recorded?

Tony Chin: I don’t remember exactly, maybe about three.

Q: Once it was recorded, did anyone realize how big of a [hit] song it’d be?

Tony Chin: No. But that same day, we recorded “Mr. Brown.” I played the lead guitar. When Bob was singing this song initially [in the studio] it was “Duppy Conqueror” him a-sing. That’s [the song] we made the riddim for. But a month or two later, when it was released, they put [the riddim] on “Mr. Brown.”

Q: Did someone in the studio re-master, or re-record the song?

Tony Chin: I heard the rumor that Glenn Adams, the keyboard player, wrote the song “Mr. Brown.” And [Lee] Scratch [Perry] didn’t like how it was feeling for “Duppy Conqueror.” Maybe [He thought] the sound was better for “Mr. Brown.” So [Scratch] re-recorded over “Duppy Conqueror” with Family Man and dem. That’s the history of that song.

Q: When I interviewed Roger Steffens, [author of the most] definitive book about Bob Marley to date, “So Much Things to Say,” I remarked to Steffens that, for me, the best parts of [his] book are those that concentrate on what made Bob such a great artist – what his process was. Specifically, how he was able to, by being such a perfectionist when it came to his music, elevate the talents of the musicians who played with him; how he made them be better at what they did. How he made them explore things musically and challenge themselves; come out of their comfort zones. And so I was really struck by your story about how you actually fussed and fought [with Bob] that first time you played [together] – all in service to the music!

(Tony Chin)

Tony Chin: Yeah, because Bob [was] a perfectionist. To me, Bob was a genius in music. Because I used to hear Bob [singing] on the radio or at a dance before I ever met him. I admired him. I loved him. When I went to the studio and saw these three guys [Peter, Bunny, and Bob] singing, all their harmonies were so perfect. I said, “Man, these guys got it.” Yeah, [Bob] and I first got in an argument [when we met], but after [“Sun is Shining” and “Mr. Brown”] were recorded, we became good friends.

Q: Indeed in John Masouri’s book “Wailing Blues: The Story of Bob Marley’s Wailers,” Masouri writes that you still cite “Bob Marley as being [your] biggest inspiration –

Tony Chin: He is.

Q: – and [have] often relayed [your] joy at being picked up by Bob Marley and driven to Johnny Nash’s house for [rehearsal] sessions with the Wailers.”

Tony Chin: Yes. Yes!

Q: I have a few questions about that. It might seem a bit random, but what car would Bob pick you up in?

Tony Chin: It was either a white or a red Toyota.

Q: So he didn’t have his BMW yet?

Tony Chin: No, no, no! Listen, at that time, Bob wasn’t famous in America, you know? Him dreads was just start to grow. So he came to my house on Spanish Town Road. I remember that he’d park across the street at a bus stop, where you’re not supposed to park.

Q: Why would he do that?

Tony Chin: Those days, the English was controlling Jamaica, right?

Q: This was before independence?

Tony Chin: Before independence. And he parked his car across the street at a bus stop on Spanish Town Road. And crossed the street and came into my yard. And he’d call me, “Tony! Tony! Come.”

Q: Sounds like such a rudeboy-style. He just parked, and didn’t care!

Tony Chin: Yeah man. He’d come picked me up, and take me over [to] Johnny Nash’s house.

Q: Roughly how long was the drive from your house to Johnny Nash’s?

Tony Chin: Maybe about forty minutes.

Q: And what would you and Bob do in the car?

(Stephen A. Cooper)

Tony Chin: We’d just chit-chat about music and things.

Q: Would you smoke?

Tony Chin: Ah man. When we went to Johnny Nash’s house, Johnny Nash wasn’t there. It was Peter and Bunny. And Bob. And Johnny Nash’s manager was there. And everyone was smoking spliffs. And Johnny Nash’s manager hand[ed] [his] spliff to me to smoke. And Bob said, “Tony, dis bumbaclot, don’t smoke that spliff there. Because di brother a-suck pu**y!” Never forget that! ‘Cause you know, Jamaica [is] very [taboo] about that.

Q: (Laughing) …

Tony Chin: Bob was funny (laughing). Mi say, “Bob, I don’t smoke.” Because I don’t smoke. I don’t drink [alcohol] or smoke.

Q: You don’t?

Tony Chin: No.

Q: I didn’t know that.

Tony Chin: I don’t smoke herbs or drink [alcohol].

Q: You never have?

Tony Chin: Yeah, me try it on[ce] or [twice]. But just for fun. It wasn’t nothing. Fully and I tried [it together]. But we’re not herb smokers. My friends Chinna and Santa [were] herb smoker[s]; Chinna is still an herb smoker, Santa no more. But I’ll never forget that. It’s embedded in my mind. Him [Bob Marley] say, “Don’t take that herb from that brother there. Because that brother suck pu**y.” (Laughing)

Q: (Laughing) Now is it okay if I [include that story in this interview]?

Tony Chin: Yeah man. Because it’s the truth.

Q: Who was the one [Bob] was saying this about?

Tony Chin: I think this was Johnny Nash’s manager. I think it was Danny Sims.

Q: Oh! Really!? Danny Sims!?

Tony Chin: I didn’t know who the fu*k he was [then].

Q: He was later Bob Marley’s manager too, right? And he said that about him (laughing)?

Tony Chin: Yeah. Bob didn’t care, you know? That same day, Bob took me down to his house in Trenchtown. And we were behind his house, [against] the wall. Talking about how we get robbed in the music; I’ll never forget, in Trenchtown.

Q: When Bob wasn’t focused on music, what kind of a man was he? How would you describe his character, his personality?

Tony Chin: Listen, Bob know me as a friend. We wasn’t close friends, like I would see him every day. It wasn’t like that.

Q: More of a “business” relationship?

Tony Chin: Not like “business.” Let me tell you something: A lot of people “know Bob Marley,” but Bob Marley don’t know them. That’s the difference. So the friendship that Bob and I [had] was a respect as a musician thing. Because I remember Bob was headlining a Sunsplash show. And I was playing with Big Youth on that show. And I was backstage waiting for Bob to come on[stage]. And a dread, a Rasta guy, came up to me and said, “Hey Tony, ‘Skipper’ wants to see you.” And the dread took me around to Bob’s dressing room. And Bob say, “What’s happening, Tony?” And mi say, “Yeah Bob,” and that’s about it. Bob was doing the “One Love Peace Concert,” I don’t know if you’ve heard of that –

Q: Yeah! When he brought [Michael] Manley and [Edward] Seaga on stage [together]?

Tony Chin: I played on that show with Big Youth. And the same thing again. I was backstage and Bob sent a man to come call me. And I go around and [Bob] was in a VW van or something. He said, “Tony, wah gwan?”

Q: It was a respect thing. He respected you.

(Tony Chin)

Tony Chin: Respect. Alright. The last time I saw Bob …. First, before that, in Jamaica, we did a show with Bob when he got shot. After a few weeks –

Tony Chin: Yeah. We did a show with him at a place called Tivoli Gardens. Syndicate was Tappa Zukie’s backing band. Inner Circle was in the show. A lot of people were afraid to play on that show because Tivoli Gardens was a political, gunman place. And Bob was [the] headliner.

Q: This was in the late [19]70s, maybe?

Tony Chin: Yeah. Th[is] was after Bob got shot. So after we did our show, Tappa Zukkie, Inner Circle, and everyone performed, it was Bob’s time to go onstage. Now Bob Marley’s bass, Family Man, didn’t [come]. I think his keyboard player didn’t [come]. If I remember right, Junior Murvin was there, [playing] guitar. And Bob was supposed to go onstage, but the bass player and some of the musicians didn’t show. And so Bob came to me and Fully and [asked] if we’d come up and play with him. And Fully tell Bob, “No.” He’s not going. So [I] said, “Okay, I will go.” So me and Chinna went onstage. And Inner Circle’s bass player. And [we] played with Bob that night. That was the last show we did [with Bob]. I wish it was on tape. When he performed that night, it was a miracle. A magic.

Now the last time I saw Bob, [Soul Syndicate was] on tour with U-Roy in France. And Bob was on tour[, too]. So he was at the [same] hotel [as us] in Paris. We had a night off, and I [was at] the hotel. [And] [a]ll the Wailers dem, the musicians dem, they’re friends of mine. Because we all grew up together. So I know all of them. So Judy Mowatt met me, I saw Judy Mowatt in the lobby. [She said,] “Tony, bloodclot, how you doing, man!?” Because she didn’t expect to see me in France. And she was surprised. She said, “Let me take you up to Bob’s suite.” And she took me upstairs to Bob’s suite. And [then] Tyrone Downie met me [and said], “Tony, bloodclot, it’s a long time we nuh see you! You know it’s your ridim we used to open the show! ‘Stalag’ [riddim]. (Singing and tapping out the Stalag riddim) “Marley! Marley!” Then we laugh and joke and he said, “Let me take you to Bob’s suite.”

Q: This was in Paris?

Tony Chin: In Paris, France. That was Bob’s last tour. So [Tyrone Downie] took me into Bob’s room. I hadn’t seen Bob since a long time. I hardly recognized him. His face was sunk in. His face looked skinny. And a friend of his named [Allan] “Skill” Cole was in the room with him –

Q: The soccer player –

Tony Chin: Right, the soccer player. And another dread [was in the room, too,] I [didn’t] know. And Bob said: “Tony, bloodclot! Tony, is it you or Fully? Who fu*k Carol!?”

Q: Who is Carol!?

(Stephen A. Cooper)

Tony Chin: Carol is this lady that we [knew] who lived in San Francisco. When a band [from Jamaica came] to town, she’d be the one to take them out shopping. And to get food and things [like that]. So Bob [knew] her. When she picked up Bob, Carol must have mentioned us [Soul Syndicate] being in town and [how she spent time with us]. And Bob, you know…. She was a pretty girl, but not our style. (Laughing)

Q: (Laughing) Is that what you told Bob?

Tony Chin: I don’t know. But Bob wanted to know if it was me or Fully. Because she’d always mention me and Fully. How she took us out shopping [to] buy clothes. Or [to] the supermarket. Or [to do] laundry. So the first thing Bob [wanted to know] was: “Was it you or Fully who a-fu*k Carol?” [I’ll] [n]ever forget this! And I said: “Bob, this is the first thing you ask me?” And [Bob just] laughed. [By] that time he was a superstar, you know? [Before] in Jamaica, he was famous, but not as big as he was [then]. So I didn’t want to impede too much on his time, because he was a superstar now. And I didn’t want to just [be a hanger-on]. So we just talked a little [more]. [And I said,] “Yeah Bob, nice to see you, man.” And that was the last time I saw him. Didn’t know he was going to die that next year. True story, man!

Please check back in a few weeks for Part II of this interview.

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Top photo by Stephen Cooper

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq