Reggae icon Max Romeo: “How do you fight the devil with a lawyer?”

In a career spanning fifty-five years, legendary reggae star Max Romeo’s many hit songs have brought joy to millions of fans and influenced generations of artists, including rap mogul Jay-Z, who famously sampled Romeo’s “Chase the Devil” (1976) in his 2003 song “Lucifer.”

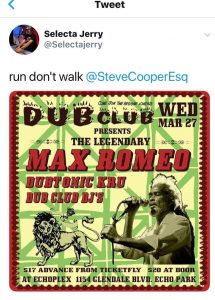

So when Selecta Jerry, host of highly respected reggae radio show “Sounds of the Caribbean,” advised me via tweet I should “run[,]don’t walk” to see Romeo perform live at the famous Dub Club in Los Angeles, I did what any sensible California-based reggae journalist would: I got on the freeway early the evening of March 27 to make sure traffic — as predictable as the jerk chicken-sellers outside the Dub Club — wouldn’t impede my ability to capture every minute of reggae royalty possible.

I wasn’t disappointed. Mr. Romeo’s performance was sensational; his music after all these years is as rootsy and righteous — and as capable of igniting a revolution — as ever. Amazingly, afterward, though I wasn’t scheduled to meet with him, Mr. Romeo graciously agreed to be interviewed in a small room behind the stage.

There amidst a motley of musicians, security guards, and lucky super fans who walked in to pay Mr. Romeo respect, we spoke for fifteen minutes about: his 2017 song “The Farmer’s Story” and the exploitation of farmers generally; Romeo’s self-owned, family-operated “Charmax” music label and recording studio in Saint Catherine, Jamaica; the most important advice Romeo’s given those of his children who’ve followed him into the music business; his friendship and collaboration with musical genius Lee “Scratch” Perry; obstacles to the Jamaican government’s proper investment in reggae; his unsatisfactory experience with Island Records; the kind of man Bob Marley was, and more. What follows is a transcript of the interview, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Mr. Romeo, it’s a blessing to meet you. I just met your son, Azizzi. He’s an extremely talented young man. And I was just talking with him about the video that you released for a tune called “The Farmer’s Story” highlighting the exploitation of farmers in Jamaica. [What were your] motivations in writing and releasing that song?

Max Romeo: Well the fact is I’m a farmer myself. I’m a part-time artist, part-time farmer. I’m into livestock. Raising cows. And goats.

Q: In St. Catherine?

Max Romeo: (Nodding) In St. Catherine. But what happened now [is] I used to be into ground produce. But I couldn’t keep up with it because it’s like working for nothing. The farmers get a very small little mass of the produce. And then when they go to the market they find the produce selling for a lot of money. So that’s what really inspired that song.

Q: There’s been a lot of news in the press about the relaxation of laws surrounding marijuana in Jamaica. Was your song [“The Farmer’s Story”] addressing that issue as well?

Max Romeo: Well it covers the whole spectrum of farming. Whatever farming you are in. All farmers have been exploited. Especially in Jamaica. It’s a worldwide thing. Cause a lot of places I’ve been in the world, [farmers] who hear the song congratulate me. And tell me, I’m telling their story.

Q: Do you think that the Jamaican government, given how Rastas have been persecuted over marijuana for so long — back to the days of Pinnacle — and after, that they will be particularly attentive to making sure that the Rasta farmer will also be able to benefit from the changes in the law?

Max Romeo: Well for now that’s not the case, but it’s shaping up to be like that in the future. Because what they are trying to get us to do, they’re getting the small farmers to work for the big farmers. It’s been that way all along. And the small farmers don’t get nothing. Everything goes in the pocket of the big farmers. [Marijuana’s] not legalized. It’s decriminalized. And that kinda mockery — because you’re still getting your herb burned in the fields. And you’re still getting the youth being arrested for herb. It’s like one step forward, two steps backward.

Q: This video [for “The Farmer’s Story”] you made with your son [Azizzi] is a beautiful video. It’s the first official video you’ve made in over fifty years of music –

Max Romeo: Fifty-five years.

Q: Did you enjoy making that video and will you make another?

Max Romeo: Yeah I enjoyed making it. Because one the beautiful parts about it is: it’s mine. I didn’t record [“The Farmer’s Story”] for anyone else. I have total control over it. And the album that the track is on is also mine.

Q: On your label the “Charmax” music label, right?

Max Romeo: Yeah.

Q: You have a lot of adult children who are now in the music industry – you discussed this onstage tonight.

Max Romeo: Yeah.

Q: Is that [Charmax] label just the family business or will you also be promoting other reggae artists with it?

Max Romeo: It’s a mixture. It’s a private studio for the family. But it’s also been utilized by the youth in the community who show potential. The gate is wide open for them. They come in and show their potential. One artist in particular [who did that] is Iba MaHr. That’s what happened in his case. He walked right in. And [Dubtonic Kru’s guitarist and vocalist] Jallanzo was there engineering when he came in. And [Iba MaHr] didn’t impress him. [But] I told him, record him. [Because] his sound [has] a little of Jacob Miller’s sound on it. And Jamaican people love Jacob Miller. And he did. And he’s [the] Iba MaHr [you see] today.

Q: Is that studio based –

Max Romeo: It’s on the farm in St. Catherine.

Q: What is one of the most important lessons you’ve told your children who are now following you into the music business?

Max Romeo: One of the main lessons I’ve told them if they want to be in the music business as long as I have is: put the music in front of the money.

Q: Nice.

Max Romeo: It took me thirty years to be Max Romeo. It [doesn’t] have to take them that long. It’s just twenty-five years ago I started to get the respect I deserved.

Q: You sang some of your famous hit songs tonight – songs that are legendary in reggae history [such as] War Ina Babylon, Chase the Devil, [and] Three Blind Mice. You made these songs together with Lee Scratch Perry in the 1970s. Scratch is still creating new music. He’s still touring. Would you ever want to collaborate and work together on new music with Scratch today, if it could be arranged?

Max Romeo: We are [still collaborating on new music together]. On my album the year before last “Horror Zone,” we collaborated on that album.

Q: Awesome. I didn’t know that. I will definitely check that out. So you still have a good relationship with Scratch up until today?

Max Romeo: Yeah. Scratch is my brother, man. (Laughing)

Q: Because you have this friendship with Scratch, [and] you guys produced [such] great music together, why did you guys break apart in the 70s? What happened to [cause] you guys to split apart?

Max Romeo: Well he took a different turn. He became a comedian. And [he] portrays this madman image. And [he] start[ed] listening to his inner-self. And that wasn’t really actually telling him the right things. So he start[ed] straying off of track. It’s not we drift from him. It’s him drift from us. I never leave him, you know? At one point, I was the only reggae artist who could actually go up to him and touch him and say, “What’s up, Scratch?” Most artists couldn’t do that.

Q: What are the biggest obstacles preventing the Jamaican government from investing more money into the development and promotion of reggae music?

Max Romeo: It’s hard to answer that question. These guys are unpredictable. You cannot peep into their minds.

Q: The government [officials]?

Max Romeo: Yeah. For some reason they feel that reggae music is “done.” And dancehall music can’t cut it. Therefore, they think it’s a high-risk business. So nobody was interested. And it was said a few months ago that [Jamaica has] made nine billion dollars off of the music industry. And I haven’t seen any put-back into it.

Q: Do you think [the] recent concert they had in the national stadium for Buju Banton — there was a lot of [worldwide] attention given to that — do you think that that will regenerate a buzz for the [Jamaican] government to [want to] participate and be more willing to [make reggae music] grow?

Max Romeo: Well Buju Banton is a one-off thing. And it’s nostalgic. We don’t know what’s gonna spur from that. What it was was an eye-opener to them that reggae still has clout. And they are saying, you know, after so many years, we have just seen the potential that reggae brings. Because Buju come from prison and put thirty-thousand people in the stadium.

Q: Mr. Romeo, is there anything that Chris Blackwell and Island Records could do to make it up to you and some of the other famous reggae artists like Third World, Toots Hibbert, and the other [stars] signed to them, when they invested [so] heavily in Bob Marley but didn’t spend enough time and investment and promotion on you all?

Max Romeo: What Chris Blackwell could do for Max Romeo is give him a statement for the sales of [the album] War Ina Babylon. And let him have some money instead of coming with this story that I was stupid to sign a contract [as a] “writer for hire.” Even a seven-year-old kid would know that a “writer for hire” contract don’t cut it. And he used that over my head from 1976 until today. That I was just merely a “writer for hire.” So Island Records owns the whole product.

Q: Do you have any lawyers that are pursuing this for you?

Max Romeo: How do you fight the devil with a lawyer? I wouldn’t waste my time. I just call it a sacrifice.

Q: I mentioned Bob Marley. We just [celebrated] his seventy-fourth earthstrong in February. Since you’re one of the few people left in the world who knew him, played soccer with him, did things with Bob, when you think of Bob Marley, what comes to mind?

Max Romeo: He was a no-nonsense guy. He was a stern individual. He was a guy that, he tells you what to do. He had that third eye to see things. It’s hard to describe Bob. He was a great guy. And his success shows you that he was great. It was just, I don’t know, he walked in the valley of the shadow of death and got caught.

Q: Mr. Romeo, is there anything else that you want to say or let the music-listening world know about Max Romeo’s music, or reggae in general?

Max Romeo: When I [got] into reggae music, I came not knowing what I want[ed] to do. At some point I started off doing things you might consider as lewd or rude.

Q: Like [the song] “Wet Dream?”

Max Romeo: Like Wet Dream and Play with Your Pussycat and all these types of songs. And then I sight Rastafari. And [I] say, alright I can’t explain this to my grandchildren further on in life so I may as well cut that out from now. And I start calling upon Rastafari. And I made a pledge to Jah that every time I open my mouth, I must be giving praise. Every time I move my hand, it must be something positive. But it’s always about Rastafari. And I cling to that until today. That’s my faith. And if it was money alone without Rastafari, it wouldn’t work. You have to have money in one hand, and God in [the other]. God without money don’t work. Money without God? That’s even worse. You see? That’s my whole concept.

••• •••• ••••• •••• ••••

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Photos by Stephen Cooper

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq