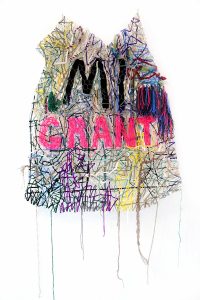

Diane Williams displays her sense of self as an immigrant and woman of color

We live in contentious times, of that there is no doubt. Anyone with at least one social media identity knows it all too well. Whether it’s foreign governments interfering in our elections — with or without the help of Americans or American institutions — the easy access to weapons of war, race, religion and immigration, there are any number of issues that divide us.

This isn’t the first time this nation has been divided, or even the worst time. We have had divisions since our inception and the worst, over slavery, pit one group of states against another — in order to form a more perfect union.

Through all these times art has echoed the zeitgeist of the nation, exposing the ruptures that set us apart. In 1934 Diego Rivera, Mexico’s most revered artist at the time, had his mural, “Man at the Crossroads” removed from Rockefeller Center in New York City because it had a portrait of Vladimir Lenin, who led the October Revolution in Russia, creating the world’s first communist nation. This capitalist nation couldn’t abide someone like Lenin being honored in such a public place. “After all, we are not communists,” to quote a line from The Godfather.

That episode inspired more art, in the form of poetry, supporting Rivera and denouncing censorship.

About 50 years ago art took another grand leap forward, after Andy Warhol upset the crabapple cart of society with his work, lifestyle and philosophy. As a kid I would read about him, his parties at The Factory and his house band, the Velvet Underground. It all looked so damn cool. That was about the time my eyes began to see a new order of things, a different view of the world. It was a time to start experimenting with freedom and art. I listened to the Mothers of Invention for the first time and tried to read Naked Lunch by Williams S. Burroughs. I didn’t quite get it, but six years later it made perfect sense.

About 50 years ago art took another grand leap forward, after Andy Warhol upset the crabapple cart of society with his work, lifestyle and philosophy. As a kid I would read about him, his parties at The Factory and his house band, the Velvet Underground. It all looked so damn cool. That was about the time my eyes began to see a new order of things, a different view of the world. It was a time to start experimenting with freedom and art. I listened to the Mothers of Invention for the first time and tried to read Naked Lunch by Williams S. Burroughs. I didn’t quite get it, but six years later it made perfect sense.

So here we are in the 21st century and art is still pushing the envelope, finding the edge and pushing the boundaries further. Some of it is a reaction, even a protest at times, to the power structure and those who seek to divide us.

At Gallery 825 in Downtown Los Angeles, Diane Williams will be exhibiting her latest show titled INcongruence. As the war against immigrants heats up and California is confronted with federal employees (your employees by the way) rounding up people of color that speak a different language, Williams put her talents and knowledge to great use to express her thoughts and emotions.

You might remember her shows Monsters and Aliens and My America. This is a young artist who has started creating her history, one that confronts and empathizes with the social and political climate that grips this nation.

Williams is an immigrant and a woman of color. She is also a graduate of California State University, Long Beach with a degree in Fine Arts. The long history of art, as ingested and interpreted by Williams, along with the socio-political drama of our times makes up the focus of her work. She questions the assumptions and norms that legitimize negative social structures, to paraphrase her own words.

With that background in mind, as well as my own upbringing and understanding of art, I asked Diane Williams some questions about her views of art and her latest show.

••• •••• ••••• •••• ••••

TF: It isn’t surprising that many artists come from working class and poor backgrounds. What are your thoughts on that?

TF: It isn’t surprising that many artists come from working class and poor backgrounds. What are your thoughts on that?

DW: Yes, many artists come from all walks of life but being an artist isn’t a walk in the park. Most artists have full time jobs and still find the time to work on their art. In a better world, we could all make a living wage from the art we create but it’s not always the case. The impending cuts and elimination of the National Endowments of the Arts, NEA in 2019 are definitely going to hit the art community in a significant way.

TF: I was thinking about the controversial mural that Diego Rivera painted for Rockefeller Center. Art should create reactions in the people that view it, do you agree?

DW: Artists make art for personal reasons. I create art to be a part of a larger conversation as well as impact my community as an agent of change. By engaging viewers in a dialogue, I am fulfilling my objective. This is the reaction I want to see. To me, context is just as important as the formal aspects in art. Coming from a drawing and painting background, my emphasis of study at California State University in Long Beach, California, I see all my artwork as paintings. The installations I’m showing at Gallery 825 are very much as formal as they are conceptual.

TF: Your current show at Gallery 825 is your reaction to the current political climate and you expect to get reactions from the viewers. Are you the type that wants the viewers to have their own conclusions and even judgments?

DW: Yes I am. Although my work is about my own identity as an immigrant and woman of color, many people resonate with the subjects of gender and xenophobia. The ones who don’t, I very much intend to include in these conversations because we’re all a part of this society. In this contentious political climate, it is important to have these exchanges in a safe and non-didactic environment. I make the work and the viewers can form their own opinions.

TF: Like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo did 90 years ago you create not for an elite class of people, but for the common folks. Can you talk about that?

DW: Both Kahlo’s and Rivera’s works rely heavily on context and the socio political environment that their artworks were created in. Kahlo’s paintings are more about her identity, inspired by her culture, gender, class and race. Like these artists, I create art that resonate, not just with me but also with many people who share the same sentiments. I often visualize my work to question assumptions and norms that legitimize negative social structures. Why does our culture maintain these societal constructs that are often outdated and harmful to marginalized groups of people?

TF: Many people are leery of visual art because they believe they don’t “understand” it. Mainly because they are not familiar with artists of the past and present. We know athletes, but not artists so therefore art can be intimidating. When I tour a museum I don’t try to understand the artists’ conclusions or even motivations, although yours in this latest show are out front. We understand racism, xenophobia and at least I view your work through that prism. What are your thoughts on that?

TF: Many people are leery of visual art because they believe they don’t “understand” it. Mainly because they are not familiar with artists of the past and present. We know athletes, but not artists so therefore art can be intimidating. When I tour a museum I don’t try to understand the artists’ conclusions or even motivations, although yours in this latest show are out front. We understand racism, xenophobia and at least I view your work through that prism. What are your thoughts on that?

DW: Art appreciation comes from understanding art and its historical context. This is why art is taught in schools and it’s fundamental for parents to introduce art to their children at a young age. Museum and gallery goers have been dropping significantly in the recent years. There is a rapid decline of interest in culture globally. Economically “squeezed” parents find investment in culture more difficult these days. There is also a decline in school trips due to lack of funding and other pressures such as conservative governments that consider any form of art as an attack on their ideologies. I mentioned the cuts of funding in the National Endowments of the Arts (NEA) earlier. This will considerably change culture, as we know it.

TF: What inspired the use of fabric and yarn for this installation? I think of it as the fabric of America is created by immigrants.

DW: That’s a great take on it and you’re absolutely right. The weaving of polychromatic fabric is a symbol of diversity. I’m always trying to reflect my community, particularly Los Angeles where I live.

These materials also have personal history, discarded or purchased from my neighborhood Thrift Shop in Glassell Park and the Fabric District in Downtown Los Angeles called Santee Alley, frequented by many lower and middle income immigrant families. I intertwined these elements into modular weavings, reminiscent of protest signs and roadside memorials operating as obstructions, confinement and disruptions. The polychromatic modules are an amalgamation of diverse textures and components. A reminder that America is clearly divided as a nation but we have more in common than we are often led to believe. Diversity is what makes this country great.

TF: My grandparents were all immigrants in the early 20th century. No one said “We have too many Greeks” (Mom) or “We have too many Hungarians” (Dad) although they were saying “no Chinese allowed.” Instead of discriminating against Chinese we are discriminating against the Spanish-speaking citizens and Muslims. It appears to me you have a more hopeful outlook on this immigration crisis, just based on what I see.

TF: My grandparents were all immigrants in the early 20th century. No one said “We have too many Greeks” (Mom) or “We have too many Hungarians” (Dad) although they were saying “no Chinese allowed.” Instead of discriminating against Chinese we are discriminating against the Spanish-speaking citizens and Muslims. It appears to me you have a more hopeful outlook on this immigration crisis, just based on what I see.

Racism and xenophobia existed in the past and exist to this day. Fear of the “other” is a powerful motivation for many people to discriminate against certain groups. I do however; have a positive outlook on the future. Cultural Anthropologists suggest that where there is homogeneity, there is less “fear of the other” but in this globalized society where people can travel easily and conveniently, more and more places are becoming diverse. Los Angeles, known as a “melting pot” of all culture is a testament to living harmoniously with other people who don’t look the same as we do. We work and live side by side and with interactions, we find some commonality. Understanding this commonality we share and also celebrating our cultural differences with empathy and appreciation can make this world more equitable.

It feels good to know activism is still alive in this nation.

The opening reception for INcongruence will be March 17, 2018, 6-9 p.m.

Tim Forkes started as a writer on a small alternative newspaper in Milwaukee called the Crazy Shepherd. Writing about entertainment, he had the opportunity to speak with many people in show business, from the very famous to the people struggling to find an audience. In 1992 Tim moved to San Diego, CA and pursued other interests, but remained a freelance writer. Upon arrival in Southern California he was struck by how the elected government officials and business were so intertwined, far more so than he had witnessed in Wisconsin. His interest in entertainment began to wane and the business of politics took its place. He had always been interested in politics, his mother had been a Democratic Party official in Milwaukee, WI, so he sat down to dinner with many of Wisconsin’s greatest political names of the 20th Century: William Proxmire and Clem Zablocki chief among them. As a Marine Corps veteran, Tim has a great interest in veteran affairs, primarily as they relate to the men and women serving and their families. As far as Tim is concerned, the military-industrial complex has enough support. How the men and women who serve are treated is reprehensible, while in the military and especially once they become veterans. Tim would like to help change that.