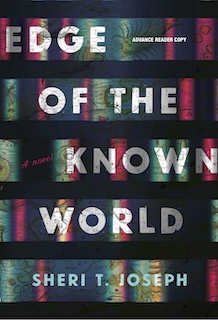

Edge of the Known World

1. THE OLD WORLD

Alex poised at the roof’s edge listening to the foghorn. She had long ago identified the distant boom as the mating call of a ghost ship trapped inside the Golden Gate. It was a perfect evening for a frustrated ghost, if not a tipsy twenty-three-year-old postdoc atop a rickety three-story fire escape ladder. The August fog howled with gale force, maddening the bay and sinking the city in premature night. Alex eyed the dumpster and alley far below. Not the ideal way to exit a graduation party, but her magic-act disappearances were the stuff of Institute legend, and her soon-to-be ex-boyfriend guarded the flat’s only door. He wanted to talk about their future.

Her choices were to face the future, sprout wings, or take the ladder. Alex did some mental math. A missed grip meant hitting concrete at thirty miles per hour. Her father’s voice echoed in her head: Stop, rag mop. Think!

A waft of brine and tar came from the shrouded piers. The flat was on Polk Street, behind the VA shelter of Ghirardelli Square, and belonged to her soon-to-be ex, a Global Security Adjunct with the exquisite name of Michelangelo Giancarlo Valenti. It was typical junior faculty housing, with wharf rats scritch-scratching inside the walls and stealing bait from traps, the steady zing-zing of Guizi Hunter video games, stained denim slipcovers, and fingerless gloves for when the heat went out. This being a bon voyage for newly minted PhDs, red plastic cups littered the warped floor, while squeaking springs from the bedrooms made rhythmic lastfling music.

The mood sang of freedom and possibility. There were no senior faculty here to bemoan a war ended twenty-five years ago—their loss of liberties, the humiliations of the Austerity or the repressive cynicism of youth culture—as if her generation had requested an intractable economic depression and psychosis of life under the constant threat of war. The TaskForce Institutes were the training ground of the Allied Nations’ civilian leadership. The days of unfettered travel were a memory, and their coveted TaskForce officer cards the gift of an international life.

Alex was the youngest of the cohort, the youngest PhD the Institute ever awarded, and the only one not leaving the backwater San Francisco campus. No one could understand why she refused field work, never mind the Fellowship at dazzling Headquarters in Shanghai. Always lie by telling another truth, a rule of omission that helped to keep her story straight. “If y’all grew up in West Texas,” she had told the others in her most entertaining drawl, “you’d find it mighty purty right here.” She was glad for the other Fellows, but also bitter, ashamed, sick with wanderlust, and if forced to happy-drawl one more time she would have ignited the flat like a rocket launch.

A chill gust of wind laughed in her face. Alex’s dark waistlength hair and pleated skirt sailed crazy around her. Stop! She clambered to the ladder in reckless defiance. Every emotion had a certain half-life. Ten rungs down and she was orange with rust, a level arm’s length from Michelangelo’s illuminated bay window, and watching her warm geek friends debate neo-capitalism and play beer pong without her. Her anger at the faceless world cooled to the loneliness of the ghost ship. Now she was freezing, her stiffening fingers making for a precarious grip. She had lived in the city for seven years yet still had forgotten her coat, hopeful as a tourist, to be schooled again by the devious summer weather.

Michelangelo came into the bay window, and Alex flattened to the ladder. Her tattered pink madras book bag varoomed with his gunning-the-Ferrari ringtone. She hooked an arm and fished madly for her phone. “Hey, you,” she answered, bird-perched in shadow. “Great party!”

“La mia bellezza del Texas!” His Italian accent rose and fell like a sine wave, free of consonants. Tomorrow he posted back to Rome, ending her first experiment in using men.

“Where are you?” he asked.

“I’m hanging out.”

He sighed in relief—so sweet, so simple. He was a fantastic if wet kisser, with a wealth of brown curls kept in perfect disarray thanks to a shelf of expensive hair products. After a few bottles of Umbrian wine, he was her prime source of classified High Council intel.

People always confided in Alex, a cursed kind of gift, as if the secret she had learned on her sixteenth birthday—the great divide of her before, and after—were a pheromone attractant for private things. So she knew Michelangelo was slumming it. His family was wealthy, nasty, and as politically connected as the Borgias. Like everyone at an ultra-elite institution, he was terrified he was destined for something great and would die before finding out what.

“Come to Rome with me, Texas,” he said. “We will be the spaghetti western.”

“I wish,” she said, watching a wharf rat the size of a pug scuttle across the alley. It stared back up at her, bold and toasty in its little fur coat. “But I’m teaching seminar. I’m trapped here.” True, with no need to add that she dare not risk the ubiquitous security g-screens across the Nations, which took Europe, Asia, and most of North America off her personal map. Peel away the ever-shifting Regional Organizations in Africa and South America, the Federation’s satellite states, the toxic red zones, and her globe became vanishingly small. San Francisco remained one of the few places with a conservative distaste for random screens. Her father’s first rule was You stay put. No chancing fate at airports, train stations, even toll plazas. The city was a jewel compared to the Plainview Penal Ranch where she lived her first sixteen years, but the spans of the scenic bay bridges were still bars.

“What about us?” asked Michelangelo.

“Let’s burn that bridge when we get to it.”

Michelangelo drooped in the window like a sunflower at dusk. Alex thought of her father’s second rule: Do not get attached. They cannot help you, and you can only do them harm. It had a corollary: Intimacy increases the temptation to confide. Keep your britches on.

That was fine in practice, as her professors joked, but what about in theory? She really liked Michelangelo. He was kind and respected limits—no squeaky springs for her. She wanted to give him something, and she had only one currency.

“Can I tell you a secret?” she said, picking one he’d like. His profile perked up. “Everyone assumes I had a hard childhood. Mom died in childbirth, I grew up in a prison, et cetera, et cetera. But Plainview was an honor farm, just an electric perimeter, with crops and livestock. Patrick, my dad, was an inmate, but also the prison doctor. He was an ex–A&M linebacker, a hyper-moral gentle giant. Everyone adored me and let me get away with murder.”

Michelangelo nodded sagely. “Sì, sì, a loving childhood always shows.”

“Sundays were holy,” she continued, transported from frigid perch to happy feral days of beating sun and scrubby plain. “We’d build tumbleweed ships from my dad’s Greek myths and have pickup football games. He always had a razzle-dazzle play. Then, when I was nine, the Creationist preacher lady started coming from Lubbock for services. She was married to Warden, so we had to go.

She preached that the War had been God’s Flood, the Diasporas the new Babel. Our Chinese Allies were granted purgatory with the Baptists; our Federation enemies were going straight to hell with the Methodists. My father despised her as an amoral hypocrite. Then one Sunday, I hid under the exam table to see why preacher lady needed a very private checkup every visit.”

Michelangelo laughed, poor bambino, and it was worth reliving those horrifying minutes scrunched beneath the exam table with her hands clapped over her ears. She had kept her father’s adulterous hypocrisy in her back pocket to brood over through the years, unable to explain his insane risk. If Warden had found out, her father would be buried in Plainview.

Tonight though, through the lens of young adulthood, she could appreciate the power of his need and loneliness. Prison was endured through a series of essential fictions. Denial allowed the sunlit moments, the small joys and anticipation that carried you through the desert nights.

Alex resumed an awkward one-armed monkey descent trying to hold the phone to her ear while Michelangelo chattered about amore. The ladder ended five feet above a stinking trash bin. She hesitated, caught on the crux of her own story. The Rule demanded another desert night alone in her twin bed piled with stuffed animals, her hands moving over her restless body. Or—she could embrace denial and climb back up to a man’s warm arms, a journey to an imagined land if only until dawn.

The foghorn brayed her location like a ghostly snitch. As Alex fumbled to muffle her speaker, a beam of flashlight hit her eyes.

“Alex Tashen!” came an imperious female voice from the street.

“Are you fucking high? Get down this instant!”

“Is that the Kommandant?” asked Michelangelo. “Oh, Texas, this is how you say goodbye?”

It was like being trapped between two advancing armies. The fumble cost Alex’s frozen grip, and she toppled into the dumpster.