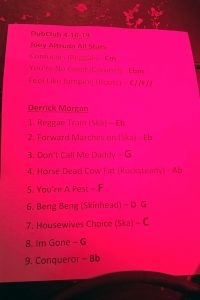

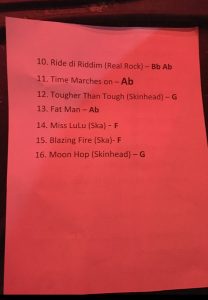

Ska King Derrick Morgan Holds Court in Los Angeles

King of Ska Derrick Morgan, a still-touring music legend who helped launch the career of (King of Reggae) Bob Marley and the careers of many other Jamaican artists, too, is a treasure. Over six decades Morgan has amassed a rich discography as impressive as any iconic international performer – replete with hit songs – songs that’ll forever mean so much to so many. As arguably no living soul knows more or has contributed more to Jamaican music in the world today, it’s an understatement that I was humbled to interview Mr. Morgan on April 10 – in his hotel room – before he delivered an unforgettably wicked performance at Los Angeles’s Dub Club.

We spoke about his memories of Bob Marley, the backstory behind the massive ska tunes “Humpty Dumpty” and “The Great Musical Battle,” the range of emotions ska music is capable of expressing, the Jamaican government’s failure to properly promote and invest in reggae music, his friendship with former Jamaican prime minister Edward Seaga, the possibility of a future collaboration with Buju Banton, and more. What follows is a transcript of the interview, modified only slightly for clarity and space considerations.

Q: Greetings, Mr. Morgan. It’s a great honor to interview you before you deliver what I know is going to be a wicked show tonight at the Dub Club. Now Mr. Morgan I want to start off by asking you [about] a book called “Bass Culture” by Lloyd Bradley, published in 2000. [In it Bradley] quotes an interview he did with Jimmy Cliff to make the assertion, “Jimmy Cliff can lay claim to being the man who discovered Bob Marley, as it was he working for Leslie Kong, who got the sixteen-year-old [Bob] his first recording session.” In the interview of Jimmy Cliff [that] Bradley quotes, Jimmy Cliff says when Bob first came to Beverley’s [record shop] “Derrick wasn’t there, just me sitting down and playing the piano.” Cliff tells Bradley that Bob told him he had some songs and that it was he, Jimmy Cliff, who selected “Judge Not” and “One Cup of Coffee,” by convincing Leslie Kong to take Bob to record the tracks (a week or so after that day Bob first walked into Beverley’s) at Federal Recording Studios. To complicate matters further, [reggae historian] Roger Steffens quotes Bunny Wailer in his 2017 book about Bob Marley for the assertion that it was [prominent rocksteady singer] Desmond Dekker who first encouraged Bob to go into the studio, and that it was Dekker who introduced Bob to Leslie Kong. Now I know you discussed these events as recently as November 2018 with Reggaeville.com’s Angus Taylor, but since this is critical reggae history – how Bob Marley was first discovered and [how he] recorded his first [two] songs “Judge Not” and “One Cup of Coffee” – could you please tell this story again in as much detail and with as much specificity as you can remember?

Derrick Morgan: Well I met Bob on Charles Street and Spanish Town Road at a bar [where] I was drinking. The girl that owned the bar, Patricia Stewart, introduced Bob to me. At that time, [Bob was a] young likkle boy. Him come to me and say: “[I] would love to do some music.” I said the only thing I can do for you [is] you have to meet me at Leslie Kong’s “Beverley’s” record shop. Because I was the man who did all the auditions for Beverley’s. I didn’t see [Bob Marley] again until about six months after when I was about to leave to England. This is in 1963. He and Jimmy came up there [to Beverley’s]. Jimmy brought him up by Leslie’s. And we sat there around the piano. And we sat down there and said to [Bob] sing this song “One Cup of Coffee.” And then him sing “Judge Not” before you judge yourself. Leslie say, “Well then, these tunes sound good. Let’s go and record it.” They do the recording at Federal Records. After we record Bob, I was to migrate to England at the same time with Prince Buster. And that was in the same [year], 1963. And after the recording with Bob, mi have three state shows. One in [the] Palace Theatre [in Kingston], one in May Pen, and one in Montego Bay. And Bob got the chance to be on two of the shows. Leslie say “we’ll put him on two of those shows.” Alright. [And] this is how I get finished up with Bob: him come to May Pen, he tried to sing the song[s]. When him started out, him dance more than how he sing on stage. So him was tired when him finished singing, right? I took him to the backstage and said, “That’s not the way you do it you know, Bob. What you must do is sing your verse first. And then after [your] solo, you start dancing in the solo, then you come back to your song.”

Q: Do you think that’s why [Bob Marley] went on to work with [Clement] Coxsone [Dodd]. [Because] he was unhappy working [for] Leslie [Kong] and with you guys?

Derrick Morgan: I don’t know if he was unhappy working with Leslie. Because Leslie was the first man for him. But the thing is, after [Bob Marley] went to Montego Bay and [sang], he followed my advice by singing and then danc[ing] [later] in the solo. And the people start boo him at the first show. And he come back with “Judge Not” before you judge yourself. And the people dem start to give him a good applause. Dem think that he just write that song after the people dem boo him. (Laughing)

Q: Now the same gentleman Roger Steffens, who wrote this book about Bob Marley, [wrote] that “Judge Not” and “One Cup of Coffee” both “failed to capture the public’s attention” and that the songs were “failures.”

Derrick Morgan: They were. I agree with that. Because they didn’t become hit songs. I leave to England in 1963 now with Prince Buster and that’s when Bob leave Leslie’s and went by Coxsone’s. So I didn’t know nothing about Bob [after that].

Q: Last month I interviewed Duckie Simpson from Black Uhuru. And while we were talking about what the atmosphere was like when Haile Selassie visited Jamaica, Duckie said: “You have to understand the people dem in Jamaica do not like Rasta. So they were all trying to act like we are all stupid. They didn’t like Bob Marley neither, don’t let them fool you. All these baldheaded singers in Jamaica. All these singers that used to sing rocksteady and ska? They hate Bob Marley. All of them. I am from that era.” What are your thoughts about this statement from Duckie Simpson and, as far as you know, were there any bad feelings or ill-will between the established rocksteady and ska singers and Bob Marley – due to Marley’s success –

Derrick Morgan: I know nothing about that. No one hate[d] Bob Marley. No one. That could never be true. Because Bob Marley was a singer that, though great, [never acted like] him bigger than anyone. He was that great.

Q: One last question about Bob Marley. Are there any specific personal memories that come to mind when you think of Bob Marley – things you won’t forget? That you cherish.

Derrick Morgan: You see, Bob and I [were] never close. We were never close. From [after doing] those state shows that we did [in Jamaica], and then I leave to England, I never have nothing to do with Bob no more.

Q: I see. It has been written and said that ska’s upbeat tempo [epitomized] in songs like your famous “Forward March” which became an anthem for Jamaica after the country achieved independence, reflected a new, optimistic, cheerful mood for the country. Almost as if everyone had a new bounce in their step.

Derrick Morgan: Yeah.

Q: But then because of the uncertainties and tough realities that existed after independence in Jamaica, and also due to the influence of Rastafari, that the beat slowed down from ska [to rocksteady and eventually] to reggae, and the lyrics and themes became more serious and socially conscious. Now I was thinking about this generalization recently – and while there may be truth in it – there are also ska songs whose lyrics aren’t cheerful or jaunty at all in the message they’re delivering.

Derrick Morgan: Yeah.

Q: They maintain the normal ska tempo, but [there are plenty of ska] songs that are really pretty somber. Would you agree?

Derrick Morgan: Yes, I agree with that.

Q: One song [like that] I was thinking about when I was thinking about meeting you today is a song I love of yours called “Humpty Dumpty.”

Derrick Morgan: That’s [Eric] Monty Morris’s song.

Q: But you sing the song all the time.

Derrick Morgan: Yeah, yeah.

Q: Eric Monty Morris was a close friend of yours growing up?

Derrick Morgan: Yeah that’s right. We grew up together.

Q: You’ve often said he doesn’t get the respect that he should [as an artist]?

Derrick Morgan: Yeah.

Q: So he wrote the song “Humpty Dumpty”?

Derrick Morgan: It’s a nursery rhyme.

Q: Yes. But it’s a mixture –

Derrick Morgan: It’s a nursery rhyme, but what he did – it became a big seller because everyone loved it, you know?

Q: Even though Humpty Dumpty has that ska beat and it makes reference to the two nursery rhymes – “There was an Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe” and of course “Humpty Dumpty,” at the end of the day, it’s really a sad and sobering song. It’s a song about poverty –

Derrick Morgan: Yeah.

Q: And hardship?

Derrick Morgan: Yeah. [Eric] Monty Morris put those lyrics together. [And] I took [Eric] Monty Morris to Prince Buster with [that] song. He and I went to [Prince Buster at] Hi-Lite Records doing one named “Now We Know” – that is one that I wrote. And he did the harmony with me. And one called “Nights Are Lonely.” Monty and I. Well “Now We Know” bec[a]me a number one seller in Jamaica. When I went to Buster now, doing some tunes with Buster, I took [Eric Monty Morris] with me to do “Humpty Dumpty” and “Money Can’t Buy Life.” Those two songs.

Q: You sing the song [Humpty Dumpty] so much and whenever you sing it you have such a beautiful interpretation. Now it makes sense when you sing about the old woman who lived in a shoe. About how she had so many children, she didn’t know what to do. And the fact they were hungry, so she fed them broth with no bread, whipped them soundly and sent them to bed – that’s harsh, but I understand it. But then when the lyrics come in about Humpty Dumpty sitting on the wall, I imagine that Humpty Dumpty is a poor ghetto youth. Maybe he’s sitting on the wall in [some] garrison.

Derrick Morgan: (Laughing) It could be – that’s the way you’re looking at it. It’s really a hymn – a nursery rhyme. When we were likkle in school we get those songs to sing. (Singing) “Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall,” you know? (Laughing) Or, (singing) “Three little blackbirds sitting on a wall, one named Peter, one named Paul. Fly away, Peter. Fly away, Paul. Come back, Peter. Come back, Paul.” And Monty sing those songs. And put them in a melody.

Q: The “Great Musical Battle” is also one of my favorite songs, the battle between Bunny Lee and Sir Coxsone Dodd. What was the genesis of that song; how did you come up with [it]?

Derrick Morgan: The thing is that every song that Coxsone make, Bunny Lee would go in the studio and make them over. And use the same artists that Coxsone used.

Q: (Laughing) So he’d rip Coxsone off?

Derrick Morgan: Yeah. And then Coxsone vexed with Bunny [because of] that. So Bunny come to me and ask me to do this song. (Laughing) Like he and Coxsone fighting. And I just come up with that – and that’s how it goes. (Laughing)

Q: I know that Bunny Lee was your brother-in-law. And that you did tons of songs with Bunny Lee. But was there any other reason besides maybe that that it is Bunny Lee who ends up delivering the final knockout blow to Coxsone [at the end of the song]? (Laughing)

Derrick Morgan: (Laughing) Anytime Bunny Lee wanted to hurt someone he’d come to me and ask me to do it with music.

Q: Did you ever speak with Coxsone about that song?

Derrick Morgan: Not really about the song. Coxsone and I were good friends, too.

Q: He never mentioned that song to you? Never gave you grief about it?

Derrick Morgan: (Laughing) No.

Q: In February I was blessed to interview legendary drummer Sly Dunbar. And during that interview Mr. Dunbar said, “A lot of people don’t know the history of the work musicians have done in Jamaica. The Jamaican government doesn’t keep track of what recording artists do.” Do you think the Jamaican government is doing enough to preserve, document, and celebrate the history of popular Jamaican music, including reggae and its founding musicians?

Derrick Morgan: No. The government [is] not doing anything towards Jamaican music. Just of late they [have] tried to do something now. It might be this government that’s in power. Trying to do something [for] Jamaican music. But for all these years, they do nothing about Jamaican music. If you can see all over the world you have festivals going on, and you don’t have none in Jamaica.

Q: They don’t have the proper outdoor venues for it?

Derrick Morgan: No.

Q: But you’re saying now though you are starting to see a change –

Derrick Morgan: A little.

Q: If you were sitting with the top people in the [Jamaican] government, what are some of the things you’d tell them they should do to improve –

Derrick Morgan: Well it’s time they make new venues in Jamaica. They need new venues. So promoters and artists can get to go around and do songs. And have shows [that’ll bring] people in, and bring in the tourists. Like this one just done the other day. This big show with him – Buju [Banton]. A show like that and they had to use the [national] stadium. Them need venues out there!

Q: And do you wish that they would also contribute more to veterans and artists like yourself –

Derrick Morgan: Yes. Contribute.

Q: – in terms of making sure your tours are accommodated better?

Derrick Morgan: Yeah. They should contribute.

Q: What do you think are the biggest obstacles that keep the government in Jamaica from promoting one of the biggest cultural riches it has – reggae, ska, and all [ of the many popular Jamaican musical genres]?

Derrick Morgan: I don’t know. Because it’s just of late that Olivia “Babsy” Grange, the Minister of Culture, she started to help out and enter the music business. She gave us awards the other day –

Q: Yes, I was just about to ask you about that.

Derrick Morgan: Right. She gave us [distinguished musicians] awards. And another fellow gave us awards, too.

Q: You’ve been honored many times for your historic contributions to music. You received an order of distinction [from the Jamaican government] long ago. You have your own road named after you in Jamaica. I would love to come visit when I come to Jamaica – if you’ll welcome me on your road, I will come.

Derrick Morgan: (Laughing) Yeah man.

Q: And just recently, in February, you were presented with an award at the “Reggae Gold Ceremony” at the National Indoor Sports Complex in St. Andrew. And there’s a picture of you at the ceremony looking very cool as you always do.

Derrick Morgan: (Laughing) Thank you.

Q: The picture that came out in the news [shows] you laughing with former Jamaican prime minister Edward Seaga.

Derrick Morgan: Oh yeah, Eddie, that’s my boy.

Q: Did you ever record any songs for Seaga [on his West Indies Records Limited (WIRL) Label that he owned before becoming prime minister]?

Derrick Morgan: I never recorded for him, but he always helped me out. [Like] when, in 1963, Prince Buster and I went to England, [and I entered] a binding contract with [Emil] Shallit, on Melodisc Records. At that time I was singing for Beverley’s before. And when I came back, Beverley’s didn’t want to record me. Because of that contract.

Q: And Seaga helped you [to get out of your contract with Shallit]?

Derrick Morgan: Seaga helped me by getting me out of that contract.

Q: I thought I read somewhere that one of the ways [Seaga] helped you [to get out of the contract] was that he told them a man who can’t –

Derrick Morgan: See. (Laughing)

Q: – see, can’t sign a legal contract.

Derrick Morgan: Right. That’s exactly it. And Shallit release[d] it.

Q: Now I’m not pointing at Seaga or any particular politician, but many observers have said that politicians in Jamaica have a history of exploiting the music when it serves their purposes. When it’s politically expedient for them to do that. That they use reggae music for advancement but don’t really love and respect it. What do you think about that?

Derrick Morgan: Well it might be, yes. Because P.J. Patterson, when he was prime minister, he used to have a lot to do with [famous ska band] the Skatalites. I think he used to manage them.

Q: Oh yeah? P.J. Patterson? The former prime minister?

Derrick Morgan: Yeah. He used to manage [the] Skatalites and ‘ting.

Q: When you say you were friends with Mr. Seaga, to go back to him for a second, do you see him often in Jamaica?

Derrick Morgan: Anytime I wanna see him I could see him, you know?

Q: Is he a politician who does respect the music?

Derrick Morgan: He respects music. And cares about it. And cares about artists, too.

Q: To this day?

Derrick Morgan: Yes.

Q: Mr. Morgan, 14 years ago in an interview with Xavier Murphy for Jamaicans.com, you said that Buju Banton’s promoters had contacted you for some advice and to do a possible collaboration together. Have you seen or spoken with Buju Banton since his release from prison [in the U.S. and his return to Jamaica]?

Derrick Morgan: No.

Q: If it could be arranged in the future, would you want to collaborate with Buju?

Derrick Morgan: Oh yes. [Buju’s] my boy. Happy to [collaborate with him].

Q: What does the rest of 2019 hold in store for Derrick Morgan? What are you looking forward to? And lastly, is there anything else that you’d like to say to all of your fans all over the world?

Derrick Morgan: Still doing shows. Going around doing some state shows, [shows in] Europe, come back into the U.S. and so on. After that I would like to go back home. And into the studio. Work with some young artists.

Q: Who are some of the young artists you would like to work with?

Derrick Morgan: I’m looking at new talent.

Q: Like who?

Derrick Morgan: I don’t have nobody’s name yet. I would like to start off some new artists. Hear their sound, record them, and then put them out. That’s what I would love to do now.

Q: When you’re not making the music and enjoying your wife Nellie, what else do you do to keep yourself happy?

Derrick Morgan: Oh – um.

Q: Besides work. Or is it just music and Nellie?

Derrick Morgan: Just play around. (Laughing)

About the Author: Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. Follow him on Twitter at @SteveCooperEsq

Photos by Stephen Cooper unless otherwise noted

Click photos to enlarge

Stephen Cooper is a former D.C. public defender who worked as an assistant federal public defender in Alabama between 2012 and 2015. He has contributed to numerous magazines and newspapers in the United States and overseas. He writes full-time and lives in Woodland Hills, California. His twitter is: @SteveCooperEsq