Amazon Rainforest Could Be Gone in 30 Years

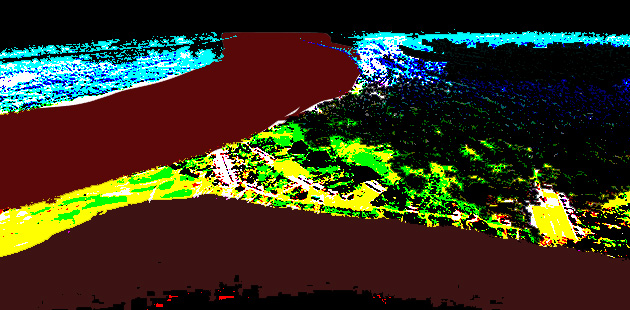

Amazon Rainforest illustration by Tim Forkes

The Amazon Rainforest has been under threat for years, despite its indisputable ecological value and unspeakable beauty.

While the public has heard plenty of promises from Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, to protect the forest and reduce harmful emissions, the land has continued to develop into either agricultural grounds or logging fodder. The entire ecosystem has been disrupted, all for the price of comfort and, well, temporary but immediate profit.

According to Reuters, Brazil’s ecological losses have increased 1.8 % just during 2020, losing roughly 1,062 square kilometers (650.90 miles) of forest to greed and corruption. But logging isn’t the only issue to blame in this scenario. Farmland conversion, wildfires, droughts and pollution have ravaged the land. Currently, the UN claims at least one billion acres have been transformed into public, government or miscellaneous use since the year 1990, and that’s just an estimate.

The worth of an intact and thriving Amazon Rainforest amounts to approximately a whopping $8.2 billion , but the forest is losing its value both economically and environmentally. The world wonder spreads across Brazil, Peru, Columbia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana, with a range over millions of miles, and provides a safe habitat for not only thousands of tropical animals but at least 500 local tribal communities.

In a cycle of connection, every bit of life in the Amazon exists to maintain an environment that cultivates that life, from animal waste that adds to the soil nutrients to the food chain that keeps its variety of organisms in check. Commonplace flavors like cinnamon, pepper, coffee, chocolate and vanilla all find their roots in the Amazon, and roughly six percent of Earth’s oxygen as well.

The destruction of the forest takes a toll on the Amazon’s ability to absorb CO2, a new study found. An estimated one fifth of affected land now produces greenhouse gases where it once acted as a carbon sink. At a time when we most need a reliable tool in the fight against swift climate change, these studies point to an opposite outcome — unless something is done before more trees disappear.

Professor Carolos Nobre, co-author of the noted study, told BBC, “It could be showing the beginnings of a major tipping point.” He predicted that current actions could lead to a savanna-like landscape within 30 years, transforming from lush rainforest into dry grassy plains.

“[The Amazon] used to be, in the 1980s and 90s, a very strong carbon sink, perhaps extracting two billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year from the atmosphere,” stated Nobre. “Today, that strength is reduced perhaps to 1-1.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year.”

“In our calculations,” Professor Nobre said, “if we exceed that 20-25 percent of deforestation, and global warming continues unabated with high emission scenarios, then the tipping point would be reached.” We are currently, he stated, at 17 percent.

But doomsday isn’t necessary nigh, say other scientists. While the general consensus indeed points to a serious and impending environmental concern, timelines are arbitrary due to the number of factors and possible lurking variables at play. Scientist and UCL professor, Simon Lewis, spoke to this uncertainty around global warming predictions.

“Some people think (the tipping point) won’t be until three-degrees warming — so towards the end of the century, whereas other people think we could get (it with) deforestation up above 20 percent or so and that might happen in the next decade or two,” he stated in a BBC interview. “So it’s really, really uncertain.”

Despite climate change models and theory, the Amazon’s only certainty at the moment is that yes, its effectiveness as a natural weapon against climate change is decreasing, and the current leadership in government doesn’t appear to be providing tangible protection as tribes continue to fight against destructive logging and land use practices.

The Awa tribe, a group of people named one of the most threatened in the world, still maintain their existence as hunter-gatherers within the eastern Amazonian region of Maranhão. Their ability to live off the land, to use what could be dangerous and wield natural resources for the good of their people, is extraordinary. They have lived by eating small animals they cook themselves over a fire, knowing the rainforest’s secrets, and enduring changes wrought by a more urbanized world beyond their borders. Now, they face the loss of their home and their way of life.

Pirai, a tribal member, recorded his observations for a BBC reporter. “The chainsaw is still buzzing just like the days you came here,” he said. “The loggers are coming back. Loggers, farmers, hunters, invaders … they are all coming back. They are killing all our forest.”

For Pirai and his tribe, life continuing as it has relies heavily on the forest staying as it has. Instead, it’s being pillaged of its natural goods, with chainsaws in view of tribal members as they attempt to go about their lives with some semblance of normalcy.

Without concrete policy changes and alternatives to the economic benefits enjoyed by those who currently thrive off Amazonian profits, they say, it’s unclear how much longer the rainforest will survive. Watching as thousands of kilometers of land are turned into farms every year, activists and critics are calling out the empty political promises of leaders, specifically politicians such as President Bolsonaro of Brazil.

We have the data, and the survival of rainforest and all who live there is at stake, and with that comes mass consequences for the rest of us: air quality and environmental impacts for years to come.

Megan Wallin is a young writer with a background in the social sciences and an interest in seeking the extraordinary in the mundane. A Seattle native, she finds complaining about the constant drizzle and overabundance of Starbucks coffee therapeutic. With varied work experiences as a residential counselor, preprimary educator, musician, writing tutor and college newspaper reporter/editor, Megan is thrilled to offer a unique perspective through writing, research and open dialogue.